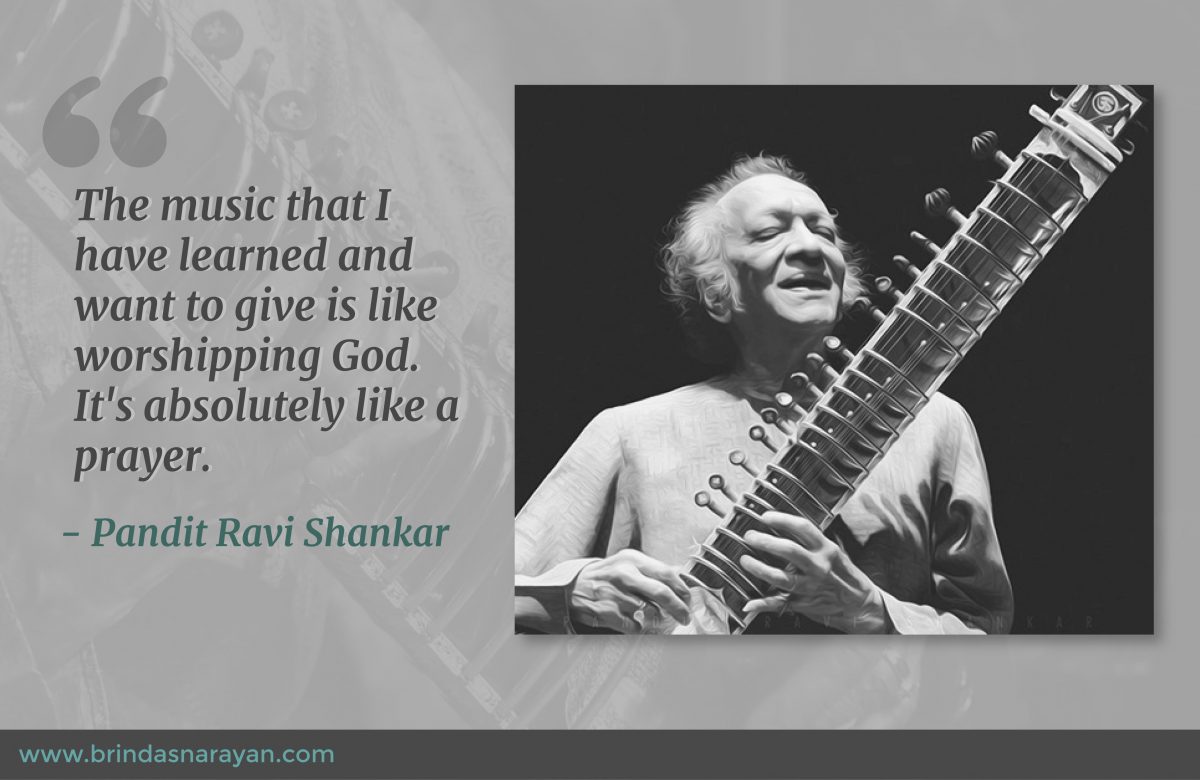

The Making of a Genius: A Profile of the Sitar Maestro, Pandit Ravi Shankar

Though Ravi Shankar was born in 1920, when India was still a British colony, he led a fabulously avant-garde life, combining in his creative persona, elements of the East and West. It’s fascinating to examine fragments from the life of the intensely inventive global icon.

His Early Childhood at Varanasi inside A Bengali Bhadralok Family

Ravi Shankar’s parents were Shyam Shankar and Hemangini Devi, a Bengali couple living in Benares. Shyam Shankar was a middle-temple barrister and a Dewan of Jalwahar, Rajasthan. With its roots in the Bengali Bhadralok, the family was embedded in a culture that was modern in outlook but deeply rooted in tradition, mimetic in some aspects of the West but intensely critical of foreign ways, assertive about nationality but also keen to conquer the globe.

The first ten years of Ravi Shankar’s life were spent at Varanasi, the magical, ancient city of which Mark Twain famously said: “Benares is older than history, older than tradition, older even than legend, and looks twice as old as all of them put together.” Shankar entered a formal school at the age of seven, but his nostalgic recollections in My Music, My Life linger only on his brushes with music and religion. His father, a Sanskrit scholar and trained musician, had left for London to work as a barrister, where Dada (Uday Shankar) too was being trained as a painter at the Royal College of Art.

A Father’s Absence Is Compensated by his Deep Attachment to his Musical Mother

Shyam Shankar seems to have been largely absent from the life of the maestro, who, as the youngest of five brothers, was closely attached to his mother. Hemangini was a soft-spoken woman with a deep appreciation for music, and her lullabies remained imprinted in his memories of his childhood.

Lonely Inside the Magical City, Ravi Shankar Plays with Instruments

His older brother Rajendra, who was a member of a musical club, had stored second-hand instruments in the home. An enchanted Ravi Shankar, plucked at the strings and fiddled with the instruments with the jittery excitement of transgressing into a forbidden space: “I had the feeling I might be scolded for it if anybody found out, but later, I surprised the whole family by playing some of the songs I had heard Rajendra practice.”

Besides the musical and artistic influences inside the home, he was stirred by the allure of Benares, by the early morning chants, by the colorful processions, by the constant intermingling of gods and people, amidst clanging bells and soulful shehnais, besides a Ganges shimmering with sunsets and floating lamps. He was drawn to the drama and the music, to the pageantry of the Durga festival, to walls plastered with godly posters: “To me, just as to any other Hindu child, all the gods and avatars were like wonderful people who we knew well and loved very much.” Yet, he didn’t recall his early childhood as an idyllic period: “[It] was not a very happy time, and I was, except for the diversions I invented for myself, rather lonely.”

He Departs Suddenly for Paris in the 1930s and Encounters a Dazzling Metropolis

Soon, however, his life was to take an unusual turn, especially for an Indian child of that generation. Along with his mother and brothers, he set sail for Paris, where Uday Shankar was leading a dance troupe. The journey involved many new sights – the moving trams and perfumed ladies of Bombay, a floating Venice – till they reached the French capital.

Paris dazzled with the lights and movement of an emerging modernity, in stark contrast to the antiquity and squalor of their native Varanasi. Despite the lingering fears of the recent economic depression, the city, in the 1930s, was still a Mecca for artists, intellectuals, writers and performers. Some of the famed visitors and inhabitants included Ernest Hemingway, T.S. Eliot, James Joyce, Salvador Dali, Picasso, Coco Chanel, Anais Nin, Henry Miller, June Miller, Katherine Ann Porter. It was a time when intellectuals debated existentialism at Left Bank cafes, when James Joyce rewrote the norms of Modern Literature with Finnegans Wake, when Dali and Picasso painted their surrealist masterpieces, when Josephine Baker startled audiences with her decidedly erotic dancing. In the midst of this kaleidoscopic social and artistic churn, Uday Shankar’s troupe presented exotically dressed Indian dancers to a motley audience. Joyce, apparently commenting on Uday Shankar’s dance, said he moved “like some divine being.”

His Rejection and Solitariness in Paris would Feed his Music Later

Inside their rented house in Paris (set up for the Company by Alice Boner, the Swiss sculptress), ten-year-old Ravi Shankar continued to “marvel at the collection of drums and all the stringed instruments.” He was sent to a French Catholic School for two years, where he picked up the rudiments of French, but disliked his fellow-students. He found the European children uncultured, the boys brutish and nasty, preferring instead to associate with the girls. Eventually, he sought permission to quit the school and continue his education with private tutorships at home. Though he was one of the performing members of the troupe, he was granted significant freedom and time to indulge his fantasies and read books and stories of his choice: “Much later, this fantasy world, my loneliness and my efforts to grasp something unreachable all found expression through my music.”

The child Ravi Shankar is Infuriated by the Condescension Accorded to Indian Music

In the thrilling cultural landscape of the 1930s, before the Nazis occupied the city, Paris attracted musicians from far-flung places. Ravi Shankar encountered diverse performers of Western music and a stunning range of forms that stirred him deeply: Andres Segovia, the Spanish classical guitarist, Feodor Ivanovich Chaliapin, the Russian opera singer renowned for his expressive bass voice, Pablo Casals, the Catalonian cellist and conductor. These famed musicians interacted with the Shankars, and while appreciating their exotic costumed dance, were politely condescending about Indian classical music. They dismissed it as repetitive, monotonous and lacking in depth unless accompanied by dance. Ravi Shankar was hurt and also angered by these comments. “They talked as if Indian music were an ethnic phenomenon, just another museum piece. Even when they were being decent and kind, I was furious. And at the same time sorry for them. Indian music was so rich and varied and deep. These people hadn’t penetrated even the outer skin,” he said in a later interview.

But he didn’t have the training yet to prove them wrong. To assert like the Nobel Laureate Tagore had already done, the deep philosophical and rich spiritual roots of Indian art. Soon however, Allaudin Khan (Baba) was to join their troupe as a musical performer, another encounter that was to shape Shankar’s unique trajectory.

An Older Ravi Shankar Subjects Himself to a Very Harsh Sitar Training In Maihar

When an adolescent Ravi Shankar encountered Baba for the first time at the All-Bengal Music Conference in 1934, he was struck by the “fire that came from within,” a light that outshone other musicians who were decked in fancier outfits. Baba himself had gained his musical knowledge from a host of gurus, including the renowned Wazir Khan of the Beenkar Gharana, after withstanding innumerable personal trials with an extraordinary doggedness and self-subjugation.

Although Ravi Shankar, was originally contracted to become a disciple of Enayat Khan (father of Vilayat Khan) and Imrat Khan, he fell ill on the day of his initiation. In the meanwhile, he had established a secret correspondence with Baba, requesting the sacred mastery he sought. Arriving in the village of Maihar, a place far-removed from the scintillating glitz of his Parisian existence, Ravi Shankar subdued his material needs and other worldly desires to the diktats of his Guru. “It was difficult for me to go from places like New York and Chicago to a remote village full of mosquitoes, bedbugs, lizards and snakes, with frogs croaking all night. I was just like a Western young man. But I overcame all that.”

Baba who was also training his son, Ali Akbar Khan, and his daughter Annapoorna Devi along with Ravi Shankar, used corporal punishments and other punitive methods to transmit his knowledge. Though there was a time when Ravi Shankar almost quit his grim tutorship, he was persuaded by Ali Akbar Khan and his own Guru’s emotive response to stay on: “You remember at the pier in Bombay how your mother put your hand in mine and asked me to look after you as my own son? Since then, I have accepted you as my son, and this is how you want to break it?”

Eventually, Shankar withstood the rigors of everyday riyaaz, the stillness and isolation of Maihar for seven years, emerging with a solid mastery of hand and finger techniques, and the confidence to improvise within the bounds of various ragas: “The right feeling of a raga is something that must be taught by the guru and nurtured from the germ of musical sensitivity within the student. Unlike some other musicians, Baba has never been stingy or jealous about passing on to deserving students the great and sacred art he possesses. In fact, when he is inspired in his teaching, it is as if a floodgate had opened up and an ocean of beautiful and divine music were flowing out.”

A Difficult First Marriage Causes Further Anguish

During this period, he also married Annapoorna Devi, Allaudin Khan’s daughter. Their son, Shubendra Shankar, was born in 1942. Annapoorna was reputed to be a gifted player of the surbahar. Legend has it that Annapoorna’s musicianship outshone Ravi Shankar’s, and the complex feelings this evoked led to a dissonance in their marriage. The movie Abhimaan, directed by Hrishikesh Mukherjee, starring Amitabh Bachchan and Jaya Bhaduri, was reportedly inspired by their story. However, to save their marriage, apparently Annapoorna vowed to stop her public performances. In a later interview, Ravi Shankar refuted these rumors and said that Annapoorna had decided, of her own accord, to stop playing before audiences. Annapoorna, however, disappeared from the public gaze, and turned into a recluse, rarely offering interviews to journalists.

He Retains a Lifelong Reverence for Baba, his Guru

Despite the fraught ending to his relationship with his first wife and Allaudin Khan’s daughter, Ravi Shankar seemed to have always revered and exalted his Guru. In an interview with NPR, the musician Philip Glass recounted a time when he asked the Maestro a question: “I said to him, ‘Raviji, where does music come from?’ The Pandit turned to a table by his bedside and there was a picture of an Indian gentleman in what we would call a Nehru coat. He bowed down to the picture and said, ‘By the grace of my guru the music has come from him to me.’ Other aspects of Baba seemed to have impressed Ravi Shankar, and infused his own life. During their European tour (that preceded the guru-sishya relationship), Ravi Shankar brought Baba to a cathedral in Brussels, suffused with the sounds of a choir. “The moment we entered, I could see he was in a strange mood. The cathedral had a huge statue of the Virgin Mary. Baba went towards that statue and started howling like a child: ‘Ma,Ma’, with tears flowing freely.” It didn’t matter to the devout Muslim, whether the statue of was of Virgin Mary or of Goddess Sharada (of whom, he was an ardent devotee). His spirituality was deep and vast, and crossed the boundaries of any particular religion, a syncretism that was to mark Ravi Shankar’s own creativity.

At Mumbai, Ravi Shankar Insists on Musicians Being Accorded Respect

In late 1944, Ravi Shankar left for Mumbai and started making some inroads into musical circles. He enjoyed the smaller performances amidst connoisseurs who could appreciate the subtleties of ragas and talas. Though he also played in “private programs”, in the households of wealthier residents, he insisted that the musicians be accorded respect, and at the very least, attentiveness. He was among the stalwarts who rescued the classical arts from their “tawaif and nautch girl” days. Though his reputation was slowly gathering momentum, he struggled, like any poor artist, to earn a sufficient income.

Banding together with musicians and artists from Uday Shankar’s cultural center at Almora, (that closed down in 1944), he became the musical director of the Indian People’s Theatre Association (I.P.T.A). The I.P.T.A., funded by the Communist Party of India, housed the performers in a generous mansion, though artists like Shankar were careful to distance themselves from the politics and dictates of the Party.

During Intense Material and Spiritual Hardship, He Contemplates Suicide

He entered a period of extreme material and spiritual hardship, becoming the sole supporter of a large group of artists from the erstwhile Renaissance group, who were being sheltered in the Shankars’ home. Beset by financial (and perhaps, also marital strains), he planned to commit suicide, setting out an exact date, time and method (his body was to be crushed by an oncoming train). He even wrote out letters to the police and to his brother, assuming sole responsibility for his death. However, another miraculous encounter was to thwart his plans.

A Meeting with A Spiritual Guide Saves A Despondent Ravi Shankar

On the day of his planned death, he received an invitation from the Prince of Jodhpur for a private performance. While practicing for the evening’s performance in a state of despondency, he was interrupted by a stray visitor, who explained that his ‘Guru’ needed to use the bathroom. Further enquiries established that the Guru was Tat Baba, a mystic that Ravi Shankar had heard of earlier. On meeting the Guru, who seemed improbably young and filled with a strange light, Ravi Shankar found his own being flooded with an inexplicable peace. The Guru asked if he could perform for him, and an overjoyed Ravi Shankar brought forth his sitar, but was politely stalled: “No, no; not now” Tat Baba requested the maestro to visit the house where he was staying later that evening. Foregoing his appointment with the Prince (that might have given him some money at a time of great financial distress), Shankar played for the Tat Baba, who had miraculously read his thoughts and gleaned his plans. After the performance, Tat Baba said: “The money you missed tonight will come back to you many times over.” He also dissuaded Shankar from attempting suicide: “Don’t do anything foolish. Be manly and have patience.” Till the publication of his autobiography (1968) and perhaps even till the end of Shankar’s life, Tat Baba seemed to have remained Shankar’s spiritual guide: “To me, Tat Baba is not so much like a living person, but rather like a great force, and I can always feel him with me.”

At All India Radio, He Composes Music to Console A Shocked Nation After Gandhi’s Assassination

Soon after, towards the end of 1948, Ravi Shankar became the director of music for the External Services Division of the All India Radio and the composer-conductor for its newly formed ensemble of instrumental musicians. Inside the fledgling nation, and preceding the arrival of television, All India Radio must have played a critical part in shaping the population’s cultural sensibilities. In a role that seemed to offer a fair degree of creative autonomy, Shankar experimented with new forms and improvisations: “I took such ragas as Darbari, Mian ki Malhar or Puriya, and had the ensemble play the whole alap and jor movements as we play them on solo instruments, followed by a piece within a tala framework…The effect was altogether breathtaking and new, and it sounded as if the whole piece were being improvised, even though the musicians had a complete score in front of them.” He was asked to compose a special piece without tablas as the shocked nation mourned Gandhi’s assassination. He created a special melody using the notes Ga, Ni, Dha and called it Mohankauns, as a tribute to the great leader. The piece was used again in Richard Attenborough’s Gandhi, as part of the movie’s score that was created by Shankar. Towards the end of his AIR stretch, in 1954, Shankar toured the Soviet Union as part of a cultural entourage. He was thrilled to witness riveting ballets at the Bolshoi Theater in Moscow during this trip.

He Collaborates with Satyajit Ray

Ravi Shankar, by then, was already fairly well-known at a national level, especially in musical and artistic circles. But Satyajit Ray was still an unknown filmmaker, who approached the Maestro to score the music for Pather Panchali. Ray, an accomplished musician himself, was an admirer of Ravi Shankar’s compositions. Moreover, he felt that Shankar’s contribution would enhance the prestige of the production. Shankar was entranced by the film’s rushes: “I instantly knew I was in the presence of a masterpiece. It was so replete with realism, yet plucked at all the chords of your heart.” Since he was in midst of a flurry of concert tours, he scored the music in an inspired four to five hours.

Both men, geniuses in their own realms, maintained a lifelong respect and affection for each other. Ravi Shankar, later on, scored the music for three more Satyajit Ray films. At one point, Ray planned to create a documentary on the musical maestro, but the project did not fructify for various reasons. The unfilmed visual script was subsequently published by Harper Collins as “Satyajit Ray’s Ravi Shankar”. Asked to comment on Ray’s life when the filmmaker was on his deathbed, Ravi Shankar said: “He has a sense of the world and a worldview, an approach towards the universal. The way the scenes, character, story and tunes of Pather Panchali belong to the world in spite of their being rooted in a village in Bengal in something you found in Rabindranath, in Dada. Like them, Satyajit’s power to emerge as an international force lies there.”

His Relationship with Yehudi Menuhin

Deeply moved by Ravi Shankar’s musical mastery at a private soirée held in Delhi, Yehudi Menuhin invited the maestro to perform at the MOMA in New York. Though Shankar sent Ali Akbar Khan in his stead, he shared the stage with the renowned violinist at several future performances. At the Bath Festival in 1966, they played their first duet. Their artistic collaboration lasted many years, impacting Eastern and Western audiences with the remarkable merging of distinct traditions. Struck by Menuhin’s emotive response to Indian music and his constant quest for new musical knowledge, Shankar said: “I find in Yehudi the inherent quality of vinaya and the desire to search for knowledge, for, besides his fascination with our music, he is deeply interested in Indian philosophy and yoga. I think he has done a great deal to awaken in Western classical musicians an intense curiosity about India’s classical traditions.”

His Historical Association with George Harrison and the Beatles

Ravi Shankar’s most iconic ‘pupil’ and lifelong friend and collaborator was George Harrison, a member of the legendary Beatles. The two encountered each other in 1966, at a friend’s house in London and Harrison requested the maestro to instruct him in the sitar. Though Shankar patiently explained that learning it would take years of discipline and submission, a relentless Harrison landed in India for a six-week tutorship. Despite adopting a disguise and a false name for his hotel booking, the Beatles star was mobbed by hysterical young women at Bombay. Retreating to a quieter Kashmir and Benares, Harrison gleaned some of the basics from Shankar.

In later years, Harrison also performed for and produced Ravi Shankar’s Chants of India. In a television interview shortly before his death, Harrison displayed a profound understanding of the philosophy that gave rise to the ancient mantras.

He Performs at the Monterey Pop Festival, CA (1967) and Woodstock, NY (1969)

Shankar and his accompanists continued to tour the United States, Europe and even Japan, with a growing receptiveness among audiences, especially in the U.S. But his performances in two epochal rock festivals were etched forever in public memories in a manner that he may not have foreseen, and shaped the Baby Boomers’ interest in Indian music (and perhaps particularly in Ravi Shankar) in a significant way.

That the festivals were organized on opposite coasts, during the roiling 60s, soon after Kennedy’s assassination, amidst Vietnam War protests and the Civil Rights struggles, and at the peak of the Summer of Love and counterculture movement, imparted a historic significance to all the band and artists who performed at these events. The Monterey event, a first of its kind, set a template for many future rock festivals. It was a mammoth multi-day event attended by about 200,000 people, some members of hippy communes, others practitioners of free love, their spirits and tolerance heightened by psychedelic drugs. Shankar’s traditional sitar performance, sandwiched among artists like Jimi Hendrix, who famously smashed his guitar on stage and set fire to its remains, created a certain association between the Hippy movement and Indian music, that was applauded by some but criticized by others.

A Long Fruitful Life

Ravi Shankar continued to forge creative collaborations with many other artists and musicians, including the legendary composer, Philip Glass, and the Jazz musician, John Coltrane. His long and immensely creative legacy is currently sustained by his sparkling and talented daughters, Anoushka Shankar and Norah Jones, his fortunate students and by the millions of devoted listeners worldwide.

References

Shankar, Ravi, Raga Mala: The Autobiography of Ravi Shankar, Welcome Rain Publishers, Great Britain, 1997.Shankar, Ravi, My Music, My Life: Ravi Shankar, Mandala Publishing, San Diego and New Delhi, 2007.