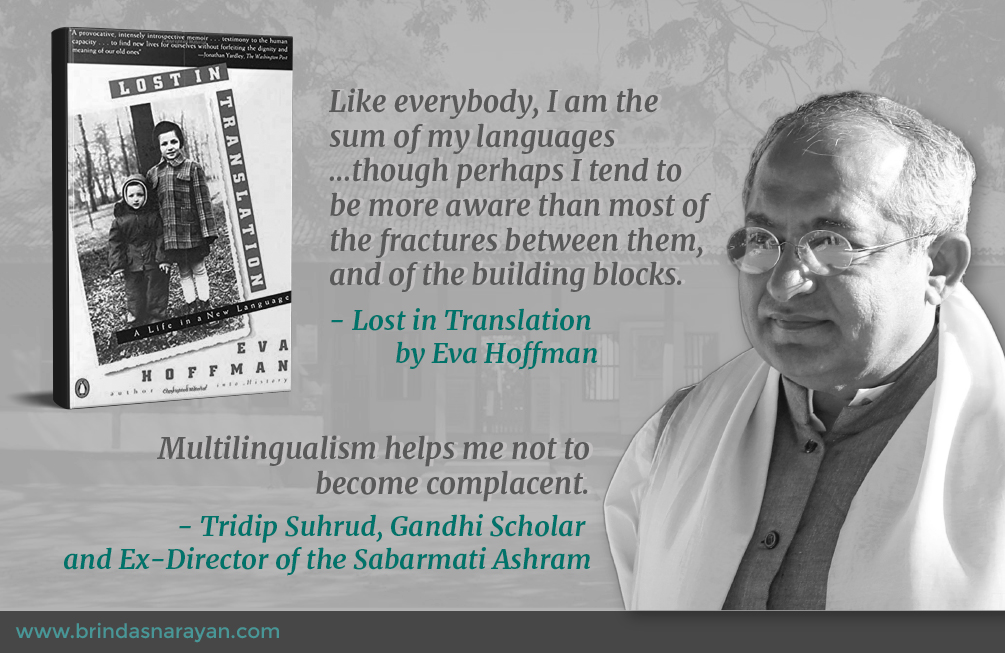

Translating Across Identities: A Conversation With A Gandhi Scholar and ex-Director of the Sabarmati Ashram

Tridip Suhrud: Injecting Movement Into His Life

With disarming modesty, Tridip Suhrud describes himself in four pithy words as a “scholar of modern Gujarat.” While he has been deeply engaged in scholarly practices, he has also, like the sunlit river that bisects Ahmedabad, coursed through a remarkable array of other roles. From being a Professor at the National Institute of Design to becoming the Director of the Sabarmati Ashram, from translating four volumes of Gandhi’s biography from Gujarati to English to annotating and contextualizing Gandhi’s My Experiments With Truth, from spearheading the archival and digitalization of the Ashram’s scholarly works to running the petty shop that sells khadi garments and books, Suhrud has infused his life with movement.

He points out that often as a scholar and professor, one builds a certain reputation and then one tends to “sit on that reputation.” Recognized as a leading Gandhi scholar with the singular ability, according to the historian Ramachandra Guha, to read, write and converse in all three languages that Gandhi himself was fluent in, Suhrud could have easily settled into a well-regarded position at any premier academic institution. Instead, he has repeatedly unseated himself and chosen to face the discomfort of shifting environs. Besides his part-administrative, part-intellectual five-year stint at the Sabarmati Ashram, he moved from the nation’s premier Design Institute to a Technology institution, where he was surrounded by peers with vastly different areas of expertise. Later, after his Ashram experience, he moved to an Architecture college. With his characteristic humility, he says, “you might think you’ve arrived, but you realize you don’t know anything about designing a building or solving some sanitation problem.”

Eva Hoffman: Negotiating Imposed Change

Eva Hoffman, on the other hand, the author of Lost in Translation, had movement imposed on her. In 1959, her Jewish family was compelled to emigrate from Poland to Canada in the face of rising anti-Semitism in her native country. Eva was only 13, and strongly opposed to the move. After all Poland still held her school friends, her favorite piano teacher, her first crush and more than anything else, an ineffable sense of herself. Even while their ship was poised to heave away from Polish shores, Eva was struck by ‘tesknota’, a Polish term for nostalgia with the added “tonalities of sadness and longing.” Raised to speak only in Polish, she knew she was being dislodged from the only semantic universe that she understood, and from the only one that understood her. As Eva herself vividly observes, “no geometry of the landscape, no haze in the air will live in us as intensely as the landscapes that we saw as the first, and to which we gave ourselves wholly, without reservations.”

As a bookish child, Eva was always drawn to the world of words. More consciously than others around her, she existed in and through language. Being able to deftly maneuver words was more than a means to transact or negotiate her terrain: “The more words I have, the more distinct, precise my perceptions become – and such lucidity is a form of joy.” In Canada, Eva acutely felt her linguistic and cultural estrangement. Her anguish emerged not only from the new language, but also from the gradual erasure of her old self: “Can I really extract what I’ve been from myself so easily? Can I jump continents as if skipping rope?”

When she was gifted a diary with a lock and key, she had to make a critical decision. What language should she use to record her deepest, most private thoughts? On the one hand, it felt strange and unnatural to use English, and yet Polish was rapidly fading into “the language of the untranslatable past.” She eventually chose English, inadvertently forging a new self: “I learn English through writing and, in turn, writing give me a written self.” Even as she actively built her vocabulary, “to accumulate a thickness and weight of words so that they yield the specific gravity of things,” she remained poignantly aware of the accompanying loss. Her Polish self was being slowly discarded, as she was “being remade, fragment by fragment, like a patchwork quilt.”

Tridip Suhrud: Negotiating Shifting Identities and Environs

Born 19 years after Eva, in the mid-sixties in Anand, Gujarat, Suhrud grew up in an intensely literate, bookish and multilingual household. While his maternal grandmother had been formally educated, his paternal grandmother had been privately tutored to read four languages and converse in three. Suhrud himself spoke only in Gujarati at home. He shifted to an English medium education much later, during his second year in college. He remarks that his parents never had any ambivalence about his being able to negotiate with English at a later stage, because his family members wrote fluently in English though none had attended an English medium school. Stories like Suhrud’s do bring into question the prevailing anxiety faced by parents who force-fit their wards into English medium systems, despite the higher costs and attendant cultural displacements that children (and parents) sometimes suffer as a consequence.

After completing his Bachelor’s and Master’s in Economics, Suhrud realized that he needed to make a shift. He chose Political Science “because it was easy to get admission into and because I knew I was only going to be a third-rate economist.” From Political Science he forayed into History and Literature, turning to the work of three Gujarati novelists for this PhD thesis. His immersion into the earlier century’s creative works led to his conviction that, paradoxically despite colonial and other pernicious social forces, “we produced some amazing scholarship, which speaks of great cultural confidence.” In particular, he cites the works of Bankim Chandra and Saraswatichandra as exemplifying a zenith of cultural creativity that has not been scaled by writers in the modern, independent nation. He wonders if creative energies, in the contemporary context, are lighting up other domains like technology and startups.

As someone who savours all forms of cultural creativity, Suhrud says he has been fortunate to work at institutions that accorded faculty with a high degree of autonomy. He leveraged such freedom to fashion highly inventive courses, which centered around themes like “100 Books I’ve Loved.” He even taught Gandhi to design students, opening up the nation’s graphical minds to the spirit that powered the iconic glasses and walking stick.

For a person who had been primarily a scholar and professor all his life, the Sabarmati Ashram experience drove different modes of experiential learning. As the Director, he not only had to oversee intellectual and academic aspects, but also more practical administrative tasks. For instance, he needed to ensure the comfort of the constant flood of visitors. Apparently, the Ashram, receives, on average, up to 3000 visitors a day. A short informal survey conducted by Suhrud’s team, over a few days, found that visitors spoke in as many as 36 languages, turning the makeup of audio or visual guides, into an intricate design problem. After primarily inhabiting texts and ideas, he now had to deal with security issues, or even the upkeep of the toilets. Despite having moved on from the Ashram, Suhrud recalls his time there with great fondness: “It was a period of grace.” He felt, by being the Ashram’s caretaker, he entered into a different kind of intimacy with Gandhi: “You begin to acquire something of that life.”

Translating Between Languages and Multiple Selves

Having morphed from an academic position into a semi-practical one, then back again into a professorial role, Suhrud is familiar with crossing bridges. In his essay, “What is Translation,” the author Rainer Schulte deploys the image of a physical bridge to describe the challenging, and almost impossible act of ‘re-creation’ that translators undertake. As a translator, Suhrud has an emotive relationship with the languages he straddles. “When you translate, your relationship with a language is far more textured and layered.”

Though his multilingual capacities were acquired organically and almost inevitably, he does sense the advantage of being able to converse, read and write in multiple languages: “It trains you to think in multiple ways. For instance, sometimes, you can think what would this mean in Gujarati?” Being a scholar, writer and translator, Suhrud’s ear is also strikingly tuned to nuanced differences between languages. Multilingualism allows him to dwell on subtle exchanges facilitated (or not) by a certain language. It gives him the capacity to ponder questions like, “How many ways can you say ‘thank you’ without burdening the relationship?”

The ability to articulate oneself precisely, using the flavors, distinctness and music of particular languages, is a gift that Hoffman and Suhrud possess. It’s a quality, too, that Hoffman believes most people prize: “We want to be able to give voice accurately and fully to ourselves and our sense of the world.” Suhrud, too, is keenly aware of how closely his identity is tied to wielding words. He feels that he can live without his institutional associations, but his ability to read, write and talk about ideas are the non-negotiable parts of his self. “For me it’s a question of staying sane,” he says.

Bibliography

Hoffman, Eva, Lost in Translation: A Life in a New Language, Vintage Books, London, 1989.

Schulte, Rainer, What is Translation, Translation Review 83:1, 1-4, 2012.