From Chief People Officer at Flipkart to the Founder of a Social Enterprise: When the Pursuit of Meaning Sparks Midlife Change

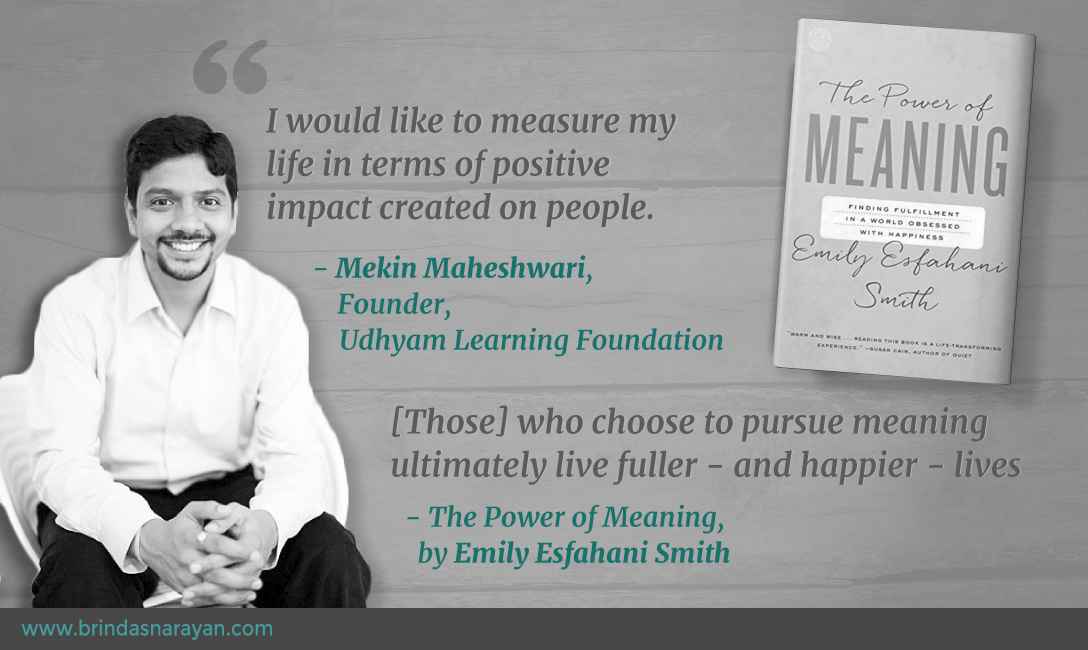

Mekin Maheshwari: Quitting A High-Status Position to Pursue Meaning

On the Udhyam website, Karthik’s toothy smile radiates into the camera. A migrant from Tamil Nadu, whose wife and two kids reside in the ramshackle Ejipura slum, Karthik runs a tea shop in Indiranagar. Besides tea and coffee, his menu flaunts dosas and rice baths, Maggi noodles and eggs, catering to both watchful and fearless eaters. After his interactions with the Udhyam team, Karthik is foraying into uncharted territories. For one, he plans to start doorstep deliveries. Weaving technology into his enterprise, he dreams like other entrepreneurs, of scaling into a chain of bakeries.

Udhyam’s creator, Mekin Maheshwari, had already achieved what many young people in their 20s can only dream of accomplishing. Being part of the founding team at Flipkart, he had experienced the heady buzz of helping shape one of the nation’s most iconic startups. In 2015, at a strategy meeting with other members, he tried to focus on the task at hand: to create a ten-year strategic plan. With his mind flitting between the future of Flipkart and his own role in that future, he was struck by an unanticipated insight: “Do I really want to do this for the next ten years?”

Logically, staying at Flipkart would have led to greater riches and the growing stature associated with a galloping business. But Mekin wasn’t the kind to succumb to logic, or to stick with trajectories that seem inevitable to other people. He listened instead to what he would later term his “gut feeling,” an inner voice that urged him to move out and create something else. While he did not know yet what his next move would entail, he was sure about his yearning for “meaning”.

From The Power of Meaning by Emily Esfahani Smith: Charting The Human Craving for Meaning in History

Leo Tolstoy

The human craving for meaning is not a new-age phenomenon. As far back as the 1870s, at the age of 50, Leo Tolstoy seemed to have it all: wealth (he belonged to the aristocratic class in Russia), renown and stature (he had already written the widely acclaimed War and Peace and Anna Karenina), a wife and kids. Yet, he was overtaken by a startling despair. Observing the lives of his aristocratic peers, he found many shared the emptiness that threatened to engulf him. Strangely, most of the peasants, who lived in hard-scrabble circumstances seemed relatively more at peace. He discovered their equanimity emerged from their faith, whether it stemmed from a religious source or from a belief in a larger force that governed their lives. Tolstoy then started writing A Confession, where he laid bare his past sins, and planned to change his own life, simplifying his material wants, and adopting more rigorous moral standards.

Albert Camus

Later, the French novelist Albert Camus was to be plagued by the same doubts that overtook Tolstoy. Born to a working-class family and of extremely fragile health, Camus was driven at a very young age to recognize the absurdity of life. When he started writing his famous, “The Myth of Sisyphus,” the start of the Second World War seemed to echo the vacuity inside him. In his novel, the character Sisyphus was cursed by the Gods to keep rolling a rock up a mountain, only to watch it roll down again, as it almost reaches the peak. Why, one could ponder, would Sisyphus persist with such a pointless pursuit? But Camus had concluded that it was such persistence in the face of meaninglessness – the hard work, the passion, the sticking to one’s relentless duty – that gave life meaning. Camus concluded that “the struggle itself is enough to fill a man’s heart.” Each one needs a “thing”, with the rock being a metaphor for one’s object in life.

In The Power of Meaning, Emily Esfahani Smith documents the manner in which meaning, which was earlier transmitted solely by our belonging or subscribing to religious beliefs, has acquired, in contemporary times, a new urgency. Many people, and especially those belonging to younger generations or those making midlife changes, seek careers that fulfil them in a more profound manner, especially if their material ambitions have already been met. Smith differentiates ‘meaning’ from ‘happiness,’ citing that the sheer pursuit of happiness would preclude us from undertaking tasks that are discomfiting in the present – like caring for a sick relative – but that would make our lives more purposeful in retrospect.

Emily Esfahani Smith’s Childhood

The author Smith herself grew up in an unusual household by modern standards. Her parents, who had emigrated from Iran to Canada, ran a Sufi meetinghouse in Montreal. As a child, she watched darvishes meditate and chant for hours, while her family tended to their meals and welfare. Since the darvishes had eschewed material longings to follow a deliberate path of self-renunciation and love, Smith grew up witnessing pathways that rebuffed modern diktats. Her own parents were welcoming of the constant influx of strangers, displaying a generosity and hospitality alien to most contemporary families. When she moved later to the U.S., Smith, was acutely tuned to the meaninglessness or void that characterized 21st Century lives, a condition that was paradoxically starker in wealthier nations.

Smith UncoversFour Pillars of Meaning

In Smith’s quest to discover the key drivers of meaning in our current age, she finds four themes. She argues that the “four pillars of meaning” are “belonging, purpose, storytelling, and transcendence.” Belonging to a particular tribe or community, whether it’s your neighbourhood or your company’s workforce or even just your family, can be a huge psychological buffer against nihilism or a sense of emptiness. Purpose would involve having an object, whether it’s pursuing a particular calling, career, or even hobby, but preferably something that provides you with fulfilment. Storytelling helps stitch your life into a narrative that feels coherent to you and imbues the suffering in your life with reason. Often, such stories have helped people reframe past traumas or negative events in their own lives to motivate or help others. Transcendence derives from larger forces – which can be religious, spiritual or even the sheer humbling knowledge of our smallness inside the limitless universe.

Mekin’s Story or Narrative Identity

Refracting Mekin’s life and decisions through Smith’s lens, one observes some of these dimensions at play. Mekin engages his strong narrative powers to frame childhood experiences – both negative and positive –that have contributed to his imaginative faculties. He reflects that his unusual capacity to envision his own future emerged from a few critical events.

After adapting to cultures as disparate as Jaipur and Kolkata, Jamshedpur and Kashmir, in the sixth grade, he shifted from a Hindi medium education to an English medium one. This is an ordeal that many Indians might be particularly familiar with, as they are flung from the grooves of a familiar language into the abyss of an incomprehensible one. Understandably, the transition was difficult: “I initially failed in all subjects except Hindi and Maths.” But remarkably, by the fourth term, he had salvaged his record, climbing back into the Top 10. That trial, however, taught him what it felt like to be culturally and linguistically excluded.

Another formative childhood moment, in Mekin’s view, occurred in the 11th Standard, when his father grappled with two job options. Recognizing that his current earnings were insufficient to fund his kids’ education and other expenses, Mekin’s father wrestled between moving to Sri Lanka or to another job. Instead of making the decision on his own, as most grownups are wont to do, he consulted his family – his wife, Mekin and his young daughter. “His having the conviction to seek our opinions for large personal decisions left a deep impression on me.” Such an event might seem innocuous or even forgettable in hindsight. But often, seemingly small and private moments such as these shape a person’s sense of agency in steering his or her own future.

Leveraging the autonomy his parents had always granted him, when picking a college, Mekin exhibited an unorthodox capacity to look beyond social rankings. Though his CET rank enabled entry to the higher-ranked RVCE, he picked PESIT. Displaying the kind of independent thinking that was to ignite his career later, he met with the Directors of both institutions. At PESIT, he sensed “ambition, construction and growth.” Moreover, the Director seemed to endorse a progressive mindset, that Mekin didn’t find at other places.

He continued to possess the courage to buck trends when it came to his job choices. After successful stints at Yahoo and with a startup that was successfully acquired, his decision to join Flipkart hardly seemed reasonable or judicious in 2009. After all, the e-commerce market was still nascent and untested, while investors hedged their bets on Search or Social Networking businesses. Most people – seasoned Venture Capitalists, mentors – advised him against Flipkart.

Again, he was tugged by what he calls his “gut feeling.” With his singular intuition for people, he had observed nuanced differences between the Bansal partners and other folks. During a meeting at the early-stage Flipkart office, he observed that the books, arriving from various suppliers, were stopped at the threshold. If a particular book had already been ordered by a customer, the package was shipped out pronto, without entering the premises. Mekin was impressed by the Bansals’ hunger to overdeliver on customer expectations, and by their almost voracious willingness to do anything and everything. Ignoring the advice of well-wishers and friends, he joined Flipkart as Head of Engineering.

Even at Flipkart, he ignored the surprise and criticism that greeted his decision to move from the Engineering function to steering Human Resources. Despite being embedded in a sector where hard, quantitative skills were prized over softer, people skills, Mekinheeded his own instincts. He realized that he had derived more joy from building the Engineering team than from other aspects of his job. He also felt his data skills would contribute uniquely to grooming human potential.

Discovering A Purpose That Leverages Interests and Strengths

Later, having decided that he wanted to move on from Flipkart, he deliberately took a gap year while plotting his next move. He knew he wanted to do something purposeful, but also something that played to his strengths and interests. With his success at cultivating human capital at Flipkart, he felt tugged by the vast but highly underserved education sector.

He made the most of his gap year, to learn intensely about the sector. He met with other experts who were already engaged with the sector in various guises. He travelled across the country, choosing to visit non-pedigreed schools and institutions that admitted more challenging student populations. Eventually, he chose to create Udhyam, a non-profit organization that imparts entrepreneurial skills to young people from low-income households and to small, grassroots business enterprises.

Expanding One’s Self and Narrative After the Move

Mekin also thinks he has changed personally after his recent career move. His wife observes that he has become more emotional and empathetic. While imparting skills to others, he has realized that he is a keen lifelong learner himself, and is hence expanding his own experiential learning in various forms. He has added new dimensions to his life, including Yoga, meditation and classical music lessons. He also thinks the young people, who enter his programs from much more constrained material and familial circumstances, are inspirations: “Their cheerfulness with their realities is inspiring.”

His advice to other midlifers who are deliberating changes is to spend time with themselves, reflecting deeply on what drives them, and who they really want to become. In addition, he urges them to meet mentors and peers from various walks of life, and to embark on various experiences as they experiment with possible futures before settling on the best fit.