Understanding the Makeup of Ukraine Through the Lens of A Revolution

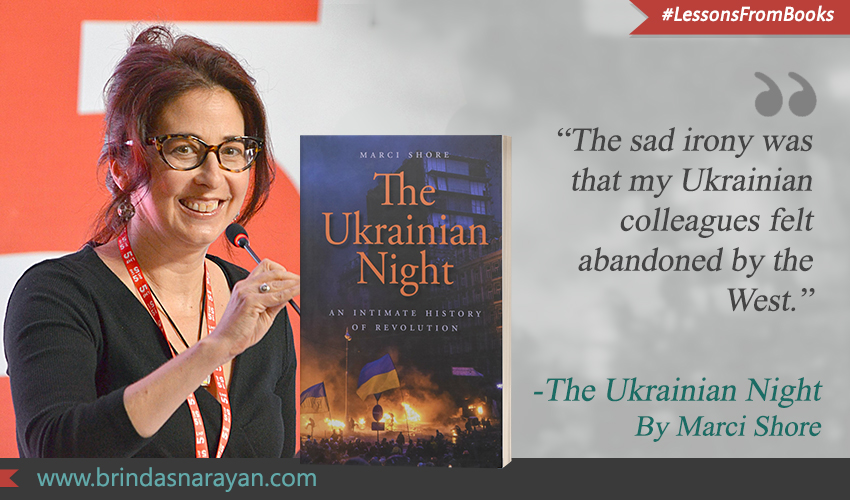

Like many others who are physically distanced from the war, I have been wrestling with my own scant knowledge about Ukraine. And belonging to a cohort that prefers to glean information from old-fashioned newspapers, books and experts, I looked for an accessible guide to the terrain. I encountered an absorbing talk on YouTube by Marci Shore, who currently teaches European intellectual history at Yale. That led me to her very illuminating book, The Ukrainian Night: An Intimate History of Revolution, which offers a ringside view to a major uprising in Ukraine in 2014 – an event called “The Maidan” because it occurred, largely, in a place called the Maidan in Kiev. (As a footnote, Maidan is an Arabic word that means ‘square’ or ‘open space’).

Shore is not only a historian but a gripping storyteller; she weaves real-time accounts of the revolution into the history, cultural evolution and social make-up of the country. She’s also fantastically multilingual. Besides English, she’s fluent in Ukrainian, Polish and Russian, all of which are necessary for anyone trying to interpret this complex East European nation. Many of her interviewees constantly switch between these languages, sometimes answering a Polish question in Russian and then reciting a poem in Ukrainian. Shore, herself, happened to be in Vienna, when this revolt was sparked off; so she was in a position to interview various actors, from multiple sides even as the nation was being remade.

The following are some of my key insights from Shore’s work:

Ukrainians Were Let Down by Their Leaders After Glasnost and Perestroika

Besides language, Ukrainian identities are also contoured by the histories of different regions in the country. For instance, many of the cohort that happened to be young and college-going when the Soviet Union fragmented into disparate, ‘new’ nations, were ecstatic about shaking off the tyrannical Soviet rule.

One of Shore’s interviewees, Jurko Prochasko, was a translator and writer, who had grown up in the Ukraine that was part of the Soviet Union. As a child, he had longed to glimpse, perhaps even possess shards of a richer past, hinted at in his mother’s memories. Though his indoctrinated teachers at school insisted that the Soviet Union had ushered in nothing but progress, Jurko believed otherwise: “It seemed obvious to him that all things from that older world – buildings, objects, art, language – were superior to what had replaced them.”

Jurko was not just attracted to ‘things’ from the past. But also to subtle gestures and expressions on older people, faint hints of a history that was being whitewashed by Soviet aggression. Or maybe it was just a revulsion towards the “Sovietness that surrounded and washed away our archaic, museum-like Galicianness.”

Though dressed in contemporary jeans when he met Shore, Jurko also lived in the past through the work he did as a translator. For instance, he translated long-dead authors like Robert Musil, Joseph Roth and Franz Kafka from German into Ukrainian. Or Yiddish authors who had been killed by the Nazis. As a young adult, when Jurko traveled to Lviv to study German philology, he was fortunate to embark on his college education at the time of Gorbachev’s glasnost and perestroika: “It meant the possibility of change, and of liberation.”

Unfortunately, for Ukraine, unlike the movements in Poland, Hungary and Czechoslovakia, their first President Leonid Kravchuk was a one-time staunch member of the Soviet Politburo. All the demonstrations leading up to his appointment seemed pointless, since the new leader was merely a member of the Old Guard.

Jurko knew, right away, that Ukraine’s trajectory was going to be more dismal than that of Poland, where the visionary Lech Walesa assumed power; or Czechoslovakia, where Vaclav Havel took the reins.

The translator also realized that he belonged to a minority inside Ukraine. Because he did not subscribe to two different extreme ideologies – Moscow’s brutal regime or the extremist “cult of Stepan Bandera.” (Bandera, who died in 1959, was a militant, far-right Ukrainian ultra-nationalist.) Jurko hankered for a gentle, cosmopolitan, liberal state, but he was living in “Europe’s forgotten fringes.” Despite a globalized celebration about the shattering of the Berlin wall, and the frothy excitement of an old system being dismantled, some countries still felt relatively friendless, unnoticed, and aggravatingly unchanged. Ukraine was one of those.

As Shore puts it: “Not being wanted was not a very nice feeling, wrote Jurko in 2011.”

The Orange Revolution (2004) Also Led to A Dismaying Outcome

In 2004, the corrupt oligarch Victor Yanukovych seized power, using all possible means. Which included rigging election results and possibly poisoning his opponent. Yanukovych, Shore observes, was an outright thug, who did not bother masking his gangsterish qualities.

In November 2004, many Ukrainians protested against the undeserving victor at Maidan Nezalezhnosti. That was the “Orange Revolution” on the spacious Maidan, which forced another round of elections in December 2004.

In January 2005, a new leader, Yuschenko, was sworn in, along with the “glamorous” Yulia Tymoshenko who became his Prime Minister. Unfortunately, things did not pan out as expected. Yuschenko and Tymoshenko started detesting each other and the corrupt ways of the old regime had started creeping back.

Jurko, in retrospect, realizes that the revolutionaries might have been naïve. They thought that handing over the country to a “good father” would solve all issues. As Jurko puts it, “And now we no longer believe in a father at all.”

“Likes” Don’t Count: Another Revolution at The Maidan (2014)

Taking advantage of the ineptitude, corruption and in-fighting inside the new regime, the old, provenly corrupt, outright thieving Yanukovych returned to power in December 2010.Unsurprisingly, his first act was to jail Tymoshenko. While his “family” (the sort of friends and acolytes that surround the mafia) started occupying gilded villas, ordinary citizens froze or starved to death. Meanwhile, gangsters extorted money from small businesses. Yanukovych himself was unapologetic about being a kleptocrat and gangster, out to loot the populace while he wielded power.

Then something changed. In November 2013, Yanukovych refused to sign a somewhat symbolic agreement with Europe. Reneging on a promise to potentially integrate with Europe really infuriated the students and young crowd – the iPhone generation – who couldn’t wait to get out of the stultifying, limited opportunities in Ukraine and move to other EU countries for internships, jobs, business collaborations, conferences or a wider life. At midnight, they started gathering at the Maidan at Lviv, drawn by the message of a journalist, who urged them on Facebook to actually show up: “Who is ready to go out to the Maidan by midnight tonight? ‘Likes’ don’t count.”

The students at Kiev were beaten by the riot police. Many parents got frantic. Yanukovych had been wrongly counting on parents to drag their kids off the streets. But he had underestimated the degree of civic frustration; because, instead, parents joined their kids. “We will protect our children,” became one of the slogans.

Some students had been hospitalized, and some had locked themselves in a monastery, fearing police retribution. Even someone like Jurko, who was no longer that young, felt compelled to participate. “It had become a revolt against proizvol – a Russian word combining arbitrariness and tyranny, the condition of being made an object of someone else’s will.”

Protesters Organize Themselves

People travelled from other cities like Lviv to the Maidan at Kiev. On the Maidan too, borders between people of diverse backgrounds started fading. For instance, academics with doctorates started talking to peasants “for the first time in their lives, and vice versa.” The Maidan, like many protest sites, became a world unto its own. People organized kitchens, tents, musicians, artists, lectures, films; cauldrons of boiling soup were accompanied by rock songs or some political lecture. It was like a city fair, a gala event with a more intense purpose. With the persistent threat of the riot police breaking in to beat people up.

The movement had drawn a very diverse set of people – left wing, right wing, socialists, nationalists, liberals and “lunatics.” But most people were there because they were fighting for a sense of personal freedom, and “choice.”

On 16th January, the tyrannical Yanukovych made things worse. He passed “dictatorship laws” which curbed more rights, including the right to gather and speak freely. It now felt like a do or die situation. While most protesters knew they were outnumbered and likely to overpowered by the State’s forces, they did not feel like they had a choice. They continued to gather at Kiev, with each one playing a role. The protest site had changed tenor too. Earlier, there was a carnival-like atmosphere. Now it became more somber, with women and children being asked to stay away.

More protesters were getting seriously wounded, not just by the police or militia, but also by thugs and criminals, who supported the President. For instance, Professor Verbitsky, a geologist, who had never been a “radical” in his life, was brutally battered to death. “He was a fifty-year-old geologist who researched tectonic movements of the earth.”

The Blurring of Time and Boundaries During Revolutions

At the Kiev protest site, what people also remembered was a strange blurring of time. It was difficult to keep track of days and dates, when one day seemed to pass to a sleepless next. As Shore notes, Ukraine is a country where a lot of Vodka is drunk. But at the Kiev site, despite the absence of Vodka, people could no longer track the passage of hours. Besides, it was so cold that protesters could not stand. They had to keep moving about in the sub-zero temperatures. Sometimes, their lips froze so much, they could not speak.

Finally, it was Poland that intervened. The Polish foreign minister, Radoslaw Sikorski perhaps risked his own life, in entering Ukraine during the uprising. To talk to Yanukovych. The Palace had a strangely “antiseptic” feel, despite the slaughter being carried on outside. Where sniper battles were being fought, where men and women, many young, some old, were being killed by whizzing bullets. Smoke spiraled towards the skies, blood spilled into the streets. Putin also had a call with Yanukovych, after which the Ukrainian leader agreed to hold elections in December 2014 and to usher in previously agreed limits on Presidential powers.

As it happened, Yanukovych did not last till December. The very next day, enraged protesters stormed into his palace, and exposed his absurd lifestyle and collections: “a boxing ring, antique automobiles, a private zoo with ostriches, and an exotic bird collection [and] a pornographic portrait of a naked Yanukovych and a loaf of bread made of gold.” Exemplifying a surprising or even stupefying restraint, the protesters did not take any of those bizarre objects with them. Leaving them instead as symbolic evidence of the tyrant’s “ostentation and absurdity.”

Russia Intervenes and Annexes Crimea

Inside Ukraine too, there were still divides between Eastern Ukraine and Western Ukraine. While most in the Western part supported the revolution, many in the East believed that the revolutionaries were fascists of a different sort. People who would impose the Ukrainian language on them, like Stepan Bandera. The novelist Serhiy Zhadan tried to convince them otherwise, but his head was bashed in, by one of the opponents.

In the meanwhile, Russian forces appeared on the terrain, as “tourists” and declared the “Russian Spring,” annexing Crimea. Vladmir Putin gave a convincing video address, saying that a vast majority of Crimeans wanted Russian rule. That he had indeed ‘liberated’ them from undemocratic forces. Shore writes: “Hannah Arendt once described old-fashioned lies as a tear in the fabric of reality; the careful observer could perceive the place where the fabric had been torn.” But with these new video-taped addresses, such tears were no longer visible. The doctoring was complete, seamless.

While Russia felt that the West (Europe) had manipulated Ukraine, many Ukrainians felt betrayed by Europe. Moreover, the Europe they had in mind, was perhaps more ideal than any of the European countries were in reality. Gandhi had long ago captured the absence of such a Europe when asked what he thought about Western Civilization. The Indian leader had responded with a mischievous and scathing: “It would be a very good idea.”

In sum, Shore found that gathering together at the Maidan pushed one to the borders of human experience, and it was impossible to emerge from such an experience unchanged. As Albert Camus puts it, there is also the strange dialectic of all rebellion. It emerges from an individual but it has to transcend the individual and “questions the very idea of the individual.” It was almost a state of transcendence, when one overcame the boundaries of one’s self and experienced an almost ecstatic solidarity with others. But such ecstasy and rapture was short-lived.

Remembering The Land of Gogol

At the end of Nikolai Gogol’s play, The Inspector-General, a country squire approached the Inspector General from Saint Petersburg with a “humble request.” He merely asked the General to tell the mighty Tsar, on his return to the capital, that there was a man called Piotr Ivanovich Bobchinsky who lived in this town.” In the end, people don’t want anything else, but to be remembered.

And so in 2014, when a political scientist called Mykola Riabchuk addressed an audience in Vienna, he did not mention that his own wife and son were in Kiev; or that his son, who was protesting at the Maidan, was at risk of being killed. When a woman asked Mykola what kind of help was needed, he responded like Gogol’s character: “Just remember that there is a country called Ukraine.”

References

Marci Shore, The Ukrainian Night: An Intimate History of Revolution, Yale University Press, 2017