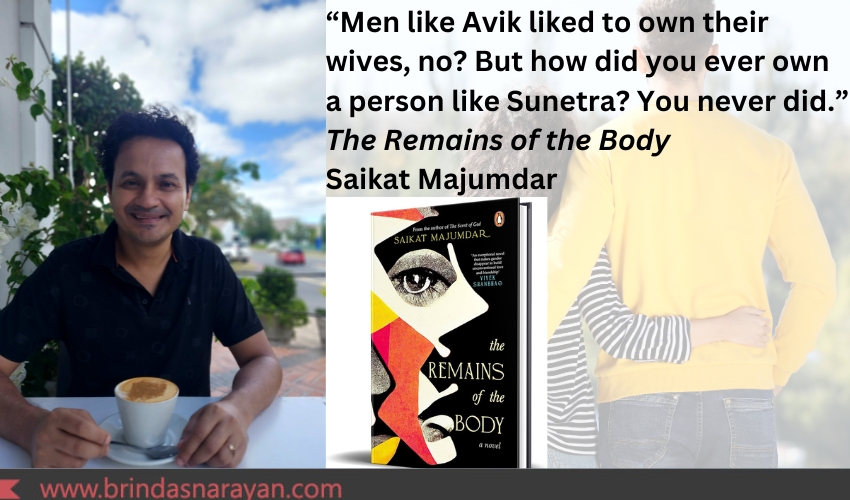

The Remains of the Body: Navigating Identity, Desire, and Belonging

We are all housed inside our bodies. Yet, many of us may not feel “at home” – perhaps because our identity or sexuality or racial or ethnic origins may compel us to feel like perpetual outsiders. At one level, Saikat Majumdar’s latest novel, The Remains of the Body, is centered around finding one’s home. In the case of his protagonist, Kaustav, a graduate student in Anthropology in Toronto, that quest for a home might have been triggered very early, during childhood, by “parents who didn’t know where he was most of the day.”

Unsurprisingly, Kaustav’s academic work revolves around homelessness and urban housing. Later in the book, a woman who tries to inhabit his worldview, or get into his skin, literally and in other ways, purloins his bedside reading, which happens to be Evicted by the Princeton sociologist Matthew Desmond. This, at a point, when she seeks eviction for herself from a bromidic, suburban existence, into a riskier but perhaps more rewarding path.

Mapping Intimacy and Desire

If bodies are our first homes, we are also subject to their geographies and histories of desire: “Avik’s body spoke an old tongue.” Kaustav is one of those rare anthropologists whose gaze shifts equally outward and inward, as curious about his unpredictable feelings and motivations as he is about the exotic or normalized “other”. In particular, he’s drawn to questioning the makeup of intimate relations, or his shifting role inside a sharply-etched “love triangle” or threesome. Constituted by his chaddi-buddy Avik, a childhood friend who at times was like a surrogate sibling or trusted confidante, Avik’s wife Sunetra – a college mate of both men – and himself.

Brotherhood Beyond Boundaries

Majumdar shines his lens on male friendship, especially among South Asian men, wherein platonic relations are often marked with an unspoken eroticism. It’s common, after all, in our cultures, to witness “straight” men link arms or playfully punch each other in ways that might be frowned upon in more rigid (for instance, Protestant) cultures. While acknowledging that there has been no “golden age” anywhere, pre-colonial settings might have licensed more gender fluidity without modern-day judgments or self-conscious labels.

Perhaps Kaustav is trying to recover a pre-modern self, a porous identity that’s open to love beyond heteronormative confines. While also heeding the centrality of a relationship that’s not characterized mainly or only by sexual needs. Like his memory-laden, explorative growing up with Avik.

Revolting Against Suburbia

Elfish Sunetra, an equally compelling, magnetic character is strong, brilliant, and also disdainful. Over time, her congealed bitterness spills into all her encounters. Her actions and remarks are pointy and knife-edged like she’s slicing and dicing her reality with a cancer scientist’s cool objectivity: “Only Sunetra could slap you without raising a finger. Just with that stone-cold sober voice.” As Kaustav learns, her resentment is justified. She has like many ultra-intelligent women, stifled her ambitions to fit into a more marriage-friendly mold.

Avik had nudged (or coerced) her into corporate research – into a path that is pragmatic but also myopic, with higher material rewards offset by deadening work. Instead of a riskier and more intellectually stimulating academic pathway. He claims he was shielding her from failure – from the ongoing frustration of applying for grants and failing to win them. But maybe he was really shielding himself from her success.

With her ambitions thwarted in this way, Sunetra despises her boxed, suburban life with Avik – his pot-bellied, middle-aged friends hanging about their home on weekends, satiated with goat curries and beer, canned jokes and reminiscences of Kolkata or Bengal: “They wanted to do nothing, all they wanted was to hear the sound of their own voices, win living room debates.” In quiet American and Canadian suburbia, immigrant dissatisfactions become enlarged. There are, after all, few other distracting sights or sounds. It’s telling that one of the most climactic scenes occurs in a snow-filled landscape, where the whisper-soft whiteness heightens the clamor of one’s thoughts.

Stability’s Weight, Freedom’s Allure

Avik represents stability and boredom, a kind of crushing sameness or comforting familiarity. Socially, he might signify immigrant success: he has a house, two cars, a job, a wife, a child, yawn, yawn, et al. Still single Kaustav deems himself a “loser” for not yet acquiring all that, but seems to possess subtler riches. Research forays into topics close to his heart, autonomy, and freedom that accompany a less encumbered life. Avik has to trudge the already trodden path but Kaustav can take dangerous detours.

Maybe Avik resents that, as flashes of forbidden or stifled feelings flit through his being. Inside a pool, Kaustav senses the heft and paradoxical softness of his friend’s body: “There was something crushing about Avik, the nakedness felt like a hug.” Majumdar shows us how bodies speak to each other in this way, a wordless exchange that draws us closer to our primitive, animal selves.

Knowing Beyond Words

Indicating that one can know without language, this is also a novel about epistemology, about the constituents of knowledge and knowing. How does one distinguish between knowing and understanding, between semantic and experiential knowledge? How does one bridge the gaps between embodied knowledge and textual or aesthetic representations?

What does it mean to know someone in the manner that Avik and Kaustav know each other? “Despite his fidgety attention span, Avik knew every inch of Kaustav’s life and never forgot a strand.” They also knew Sunetra through each other. Children are sharply attuned to such exchanges: “Children know everything, the language of the body, words you omit because you don’t think children should hear them.”

Many reviews have suggested that this is a book about sexuality. And it is. But sexuality feels like an inevitable room in a much larger home. There are many brilliant works on female friendship, like Elena Ferrante’s My Brilliant Friend, or Sally Rooney’s Conversations with Friends. The Remains of the Body fills that gap in male friendship. And also charts the story of a marriage: “It was a ferment of marriage, the toll of just nine years that made it fertile within while raising a bad odour.”

Unmasking Norms, Embracing Complexity

It’s heartening that a male writer has chosen to wrangle with domestic themes, exploring kitchen conversations and bedroom politics. While also raising incisive questions inside a taut 170 pages. Majumdar is a masterly wordsmith. His sentences never sag. They sing and prance, quiver with movement: “It always felt like Sunetra flashed something brutal at him, like a shapely machete.”

The question that stays with me, and that perhaps ought to be raised in domains outside literature is this: Is there any being on this planet who’s not ‘queer’? Who completely subscribes to constructed norms that do not reflect the diversity of human experience?

References

Saikat Majumdar, The Remains of the Body, Penguin Random House India 2024