From Berlin to Jamia Millia: A Woman’s Enduring Legacy

Jamia Millia: Sparked by a Crisis

Jamia Millia Islamia was forged by a crisis. A response to Gandhi’s call for non-cooperation required an abandoning of settings funded or supported by the British. Indian Muslims who withdrew from Aligarh Muslim University had to quickly cobble together a place that would fuse modern lessons with Islamic traditions. Sparked off from inside tents, the school and university rapidly evolved as it drew the attention of various patrons.

These events in India weren’t shielded from larger, international currents. From ideas and conversations fueled by a cosmopolitan intermingling in cities like Berlin. Where a seemingly chance encounter between three Indian Muslim men and a Jewish, German lady was to reshape not only her life – but to some extent, the evolution of Jamia too. At a 1920s party held by Suhasini Chattopadhyay (a younger sister of Sarojini Naidu) and her husband, ACN Nambiar, Gerda Philipsborn met her life-altering friends.

Opera Dreams, Silent Struggles

Philipsborn, who is the focus of Jamia’s Aapa Jaan, was born in 1895, in Kiel in North Germany, a well-off trading town. Her father and uncle, who owned shops that sold cloth and readymades, were relatively well-off. The Philipsborns were “assimilated Jews” – so they were unlikely to have worn visible symbols of their religion. Later, when the family moved to Berlin, Gerda attended the opera and theatre and finished school in 1912/13. Women were not permitted in colleges yet.

Perhaps, Gerda intended to be a professional opera singer since she entered the Berlin Stern Conservatory in 1908. Maybe she also wanted to use her singing to uplift the cause of the Eastern Jews. Even in this, she might have faced resistance. She may not have been allowed to sing Yiddish folk songs because she was not Jewish enough. And banned from Wagner because she was too Jewish.

Cultural Bonds Beyond Borders

At that Berlin party, Gerda was quite taken in by the three men – all perhaps quite suave, educated in England or Germany, but also lit by an idealism to free their country and uplift their fellow-citizens. Zakir Husain, from a landowning family in Hyderabad, had studied at Aligarh Muslim University. At Berlin, he was pursuing a doctorate in economics so that he could take his learnings back to Jamia. Abid Husain had garnered a doctorate in education at Germany, while the third, Muhammad Mujeeb held a BA in History from Oxford, and had gleaned hands-on printing techniques in Berlin.

It was Gerda who widened their cultural lives in a way that wouldn’t have been possible otherwise. As Pernau observes, though a kind of Indophilia was sweeping through Germany then, this did not involve the befriending of ordinary Indians. In general, while Indians like Gandhi and Tagore were exoticized and venerated, others were disparaged.

For instance, Carl Hagenback introduced the idea of human zoos, where he had Oriental and African tribes on display in recreated “natural” habitats. John Hagenback, his son, travelled the world for these exhibits, recruiting “specimens” who would be paid for their work. A show in Berlin in 1926 recreated an Indian village with a 100 Indians, elephants, goats, monkeys and snakes. Naturally, folks like Zakir Husain were deeply offended and protested through newspaper articles.

Since Philipsborn was shorn of any racism herself, she was an important connection: “She knew people from every walk of life.”

Friendship Forges A Middle Space

As an opera singer, she mingled with musicians and artists. And with scientists through her partner, who worked with Albert Einstein. She knew Martin Buber, the Jewish philosopher and Franz Kafka, the author. Gerda escorted her friends to “concerts, operas, plays, art exhibitions and schools.” Germany itself, was at that time, in the words of diplomat and writer, Harry Kessler, “dancing on a volcano.” But there was also joy and excitement. “Life was uncertain, and anxiety led to a frantic celebration of the moment.”

Berlin was the cultural hub of Europe, filled with cabarets and cafes, pubs and publishing houses. Gerda brought the three Indians into all this. Mujeeb developed a taste for classical music, and a deep appreciation for Beethoven in particular. Abid Husain became obsessed with Goethe’s Faust and released an Urdu version at Jamia in 1931.

Countering the Orientalism washing through Germany, and aggravating stereotypes of tyrannical rulers who were cruel to women et al, the three Muslims might have painted a truer picture for Gerda, including the potential for educating Muslims through Jamia, to make them ideal national citizens.

As Pernau puts it, such interracial friendships can bridge differences and occupy a rare liminal space: “Focusing on friendship in our narratives, Leela Gandhi has argued, is a way to move beyond the easy divide between the West and the East, between the colonizer and the colonized, as if there was nothing in between.”

Seeking Her Life’s Purpose

When her friends later returned to Jamia in 1926, Gerda might have felt alone and purposeless. Her mother had recently died, her father’s business was shut down, her siblings had moved on and she wasn’t interested in marrying the “sensible” Jewish partner, and moving to Princeton, New Jersey. Perhaps she was always too spirited for that, too drawn to radical social experiments and promises of utopia. Like to the manner in which assimilated Jews were seeking to rediscover their roots in the East.

Martin Buber, an Eastern Jew, had created a collection of stories on Hasidim. The Eastern Jews believed that they were preserving a timeless wisdom in their shtetl or small towns. Buber also believed that Jews needed to move to Palestine and that the Arabs would welcome them as “brothers.”

Attracted by Buber’s notions, Gerda headed to Palestine, where a Jewish youth movement was being forged at Ben Shemen. Her stint didn’t last long. Maybe she already sensed how Zionist echoes were likely to tilt the community into unsavory directions.

Radical Devotion, Enduring Legacy

She headed then to Jamia, landing in Delhi in 1932, staying there till her death in 1943. “Like the other teachers from Jamia, she took a pledge of lifelong allegiance.” For a minimum salary, foregoing many comforts she had been used to earlier. She was called Aapa Jaan, the beloved elder sister. Even today, one of the hostels in Jamia is named after her as is the Gerda Philipsborn Day Care Center.

The book also brings other fascinating characters to light. Like Virendranath Chattopadhyay, Sarojini Naidu’s younger brother. Chatto was considered a leader of the students and a central figure in the South Asian community in Berlin. Chatto might have been admired by his young proteges but his American lover Agnes Smedley resented the way she was expected to serve these students – “wash and mend their clothes, and provide them with meals, for which she often had to go hungry herself while Chatto shared the food with the students.”

About The Author

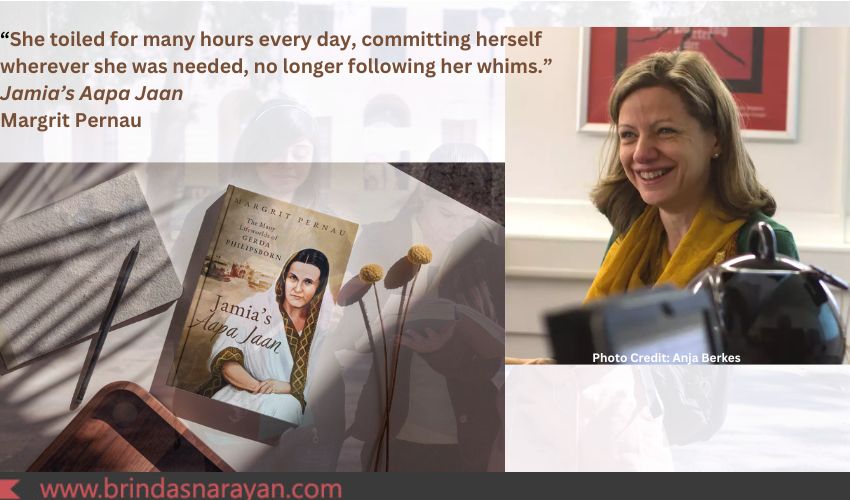

Margrit Pernau’s family has always been soaked in interrogating education. Her maternal great-grandfather was a school teacher who owned a 1st edition of Tagore’s works. Her mother did a PhD on education, her “dissertation was on the Waldorf schools and Rudolf Steiner.”

Pernau is a professional historian who brings a novelist’s sensibility to this work: evoking what it must have felt like, at times and places very different and in many ways startlingly similar to our own. It’s also heartening that we’re looking at largely male-built and male-run institutions from the lens of women who had critical, and often unsung roles in their making.

References

Margrit Pernau, Jamia’s Aapa Jaan: The Many Lifeworlds of Gerda Philipsborn, Speaking Tiger, 2024

For more about Gerda’s life, including many photos, see my 2015 article “A Physicist’s Lost Love: Leo Szilard and Gerda Philipsborn.”

http://www.dannen.com/lostlove