Between Tea Leaves and Tensions: Growing Up in Barbari, Assam

In the lush surroundings of Barbari, “a small town with a big population” nestled close to the tea garden of Kalguri, the narrator grows up in a world that feels relatively cushioned.

Barbari, with its inhabitants arriving in waves – some intentionally imported to labor, others displaced from troubled borders – can serve as a microcosm of Assam’s intricate social tangles. During the Raj, the white managers were on top, followed by Bengali Babus, with a few Axamiya (or Assamese) at the clerical periphery. The tea plantation owners, all white, lived in distant geographies, isolated from the lands that fueled their wealth. Later, when those plantations are managed by brown men, the properties remain fiercely guarded by high fences and barbed wires.

The narrator, who belongs to an Axamiya family, is shaped by a bucolic and seemingly tranquil setting, with her father claiming forest lands outside the tea estates, becoming in the process, a “virtual zamindar”. Everyone is so busy with building homes and tending to lands, simmering tensions in the State hardly ripple into their lives.

But legacies of the Raj linger. Her brother, on a dare, once shook hands with an American manager at the tea garden, a moment of awe and disbelief that led him to refrain from washing his hand for a week, trying to preserve traces of the foreigner’s touch. The narrator harbors a deep-seated fear of her school principal, Suren Dadu, who instills an inferiority complex in the Axamiya students, reflecting larger social hierarchies at play.

The Baganiya, tribals imported from Central and Eastern India to work in slave-like conditions on the tea estates, toil as agriculturalists on these converted lands. East Bengali peasants, skilled agriculturalists, are also tugged into this complex tapestry of labor and survival. Moti, a Marwari merchant in the town whose prosperity balloons from business to business, views the growing presence of Miya – Muslims from East Pakistan – with suspicion.

Still childhoods can seem idlyllic, oblivious to fissures imposed by grownups. In her school, attended by kids from “Axamiya or Bodo or Miya or Bihari or Bengali or Baganiya or Nepali” families, students mingle without heeding differences.

As the narrator grows older, she secures an MA from Gauhati University and becomes a history lecturer. Her husband, a dedicated folklorist, travels frequently for research, leaving her with the cozy tedium of a kind marriage with little companionship. When her husband warns her of an impending implosion in Barbari, she’s rattled that her childhood place, her peaceful town could shatter like other places in Assam.

She recalls an instance at school, when she could not protect her classmate Bhikhu from the casteist bullying of a Sanskrit Master. Who had let loose a volley of slurs at Bhikhu, asking him to vacate his seat for the narrator, who had arrived late, but who also happened to be the daughter of a powerful man.

She had bawled helplessly then, bewildering the master and not appeasing Bhikhu. She had felt culpable then, and feels culpable now as smoke curls up behind them, as they rush to leave their burning town. “Whoever it was, I was responsible for his death and the many deaths that would follow once we were safely on our way to Guwahati and the rioting began.”

References

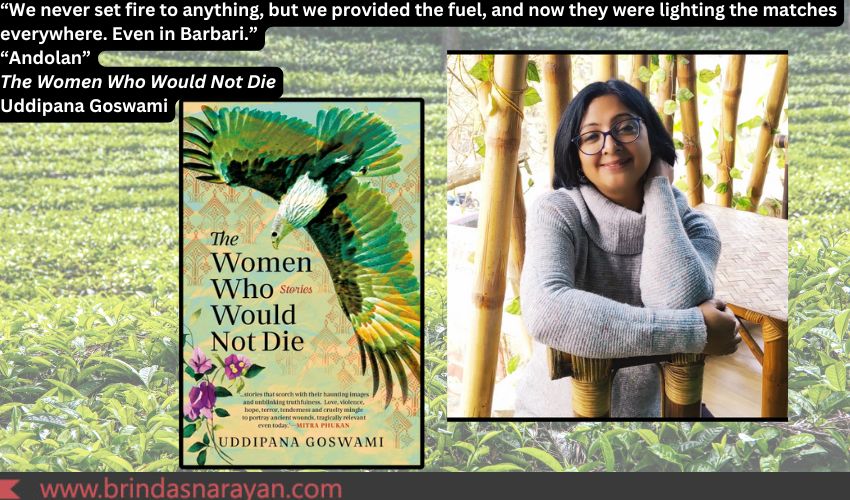

Uddipana Goswami, The Women Who Would Not Die: Stories, Speaking Tiger, 2024