Shadows and Scars: Finding Love and Identity in Assam

Assam has a rich history shaped by its indigenous cultures, the Ahom dynasty’s six-century reign, and British colonial rule. The State played a pivotal role in India’s struggle for independence but has since simmered with ethnic conflicts and movements for autonomy.

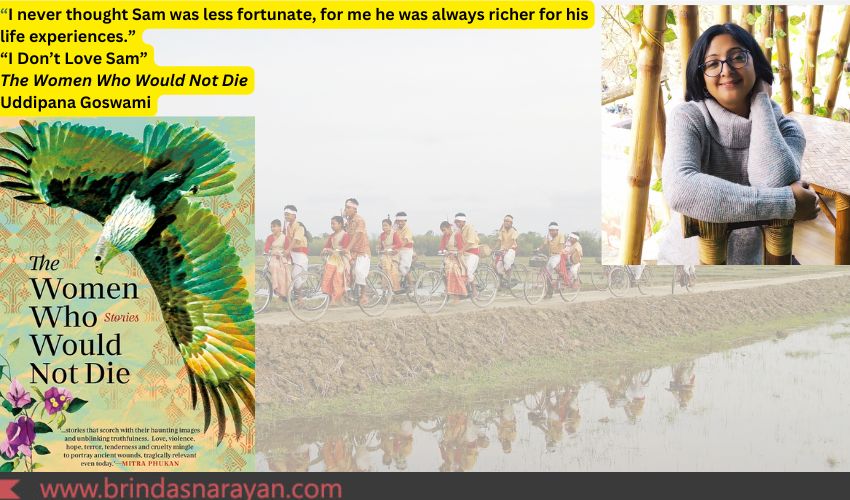

In this verdant, churning landscape, Uddipana Goswami depicts folks grappling with identity, love and the ongoing scars of never-ending revolutions. While men are also victims, it’s the women, as Goswami observes, who bear the rainbow bruises of public and domestic violence.

Forbidden Love, Quiet Rebellion

In “I Don’t Love Sam”, Jonali’s rebellion is a quiet, inward resistance against social strictures. Educated in a Catholic school, where the nuns insist on long skirts, pulled-up-to-knees socks and the banishment of all carnal thoughts, Jonali plays the “perfect conformist”, excelling in academics and in a slew of extracurriculars.

Beneath her “teacher’s pet” poise, normal adolescent feelings surge and she channels her dissent into poems that the Sisters rarely read. “My biggest rebellion, however, was falling in love with Sam.”

Shyamkanu Murmu is the original Adivasi name of the gardener’s son, whose name has been altered into the Christian-sounding, nun-pleasing Sam.

Sam and his father had lost kith, kin and everything else during riots in their town. Catholic nuns had hired many of the displaced, deploying their agricultural skills in convent or church gardens. Small-made, dark-skinned, perceptive and intelligent, Sam starts acquiring an attractive heft, as Jonali watches him from her dorm.

When Sister Theresa allows her to teach him Hindi and Axamiya, they become friends. Jonali bristles when Sister Theresa calls her compassionate for teaching “poor” Sam. The boy, after all, seems like the one who was enriched by his harsher experiences: “I always thought I was the poorer person, having nothing to offer but the false middle-class values I had grown up with and a shallow morality that had no place in real life.” She falls in love, though she is to realize later that she never really loved Sam, but loved the idea of loving Sam.

Sam does not love her back. He’s filled with derision for her, flinging terms like “oppressors”, “bourgeoisie” and “proletariat”. Later when he outgrows his communist ideology, he’s determined to reclaim his tribal identity that had been stamped out in Assam. They’re in a relationship by then, though she senses that they could never belong to each other. Sam, as he always makes clear, thinks of her as the enemy.

When they part ways, she carries a “Sam-shaped” wound inside, nursing it like a solicitous parent. After a long break, when she gets on the phone with Sam, he sounds drunk and slurry at 11 in the morning. He was partying, the previous night, with a legislator. As the politician’s henchman, Sam thinks he will climb the ranks soon, snag a ministerial berth. He talks about how this position would be a rebuke to those from his past: “You, your nuns and your people, and everybody else who always looked down upon me, pitied me, took me in so that you could feel great about yourselves. You will know.”

The hurt inside dissipates and Jonali’s free: “I did not love Sam. Not anymore.”

Escaping Hypocrisy, Embracing Chaos

In “Colours”, the unnamed narrator seeks to escape “hypocritical middle-class values” imposed by his parents, values that he thinks are suffocating and cowardly. Despite his yearning for a writer’s life, he’s coerced into a medical degree, a path he treads reluctantly and without distinction. The Kalguri tea estate, where he eventually finds work, represents not just a job, but a sanctuary—a place where he can finally immerse himself in books: in Axamiya and English works.

The tea estate, however, is no refuge from the harsh realities of the region. Dambaru, his help, becomes a tragic figure when he falls in love with Deepti, a Bodo girl. The forbidden relationship leads to Dambaru’s murder, an event that destabilizes the entire area. Deepti’s transformation from a victim to a militant embodies the brutal cycle of violence that pervades Assam, where personal tragedies are subsumed into larger political currents. The narrator finds himself tangled in a situation where boundaries between victim and perpetrator blur, where the land itself seems to conspire against peace.

Voices of Women in Conflict

In “Write Romola,” Romola’s tale, seen through the eyes of the narrator, examines the intersections of gender, class, and regional identity. Raised by a mother who juggled a full-time college lecturer job, domestic responsibilities, and a fractious marriage, the narrator grows up with a deep-seated aversion to marriage. Romola, a poor relative’s 10-year-old girl thrust into the family, becomes a companion and a surrogate mother, nudging the narrator to persist with the everyday grind of school and life.

Much later, when the narrator escapes to Delhi, she chooses to be a cultural reporter, carefully evading the “hard” news that would tether her to the grim realities of her homeland. But prejudices of the mainland towards people from the Northeast inevitably tug her to her roots, compelling her to pen a series of articles on what it really feels like to be from the Northeast. On why men in her region take to guns and bombs. Her work garners fans and eventually leads to a marriage that, even worse than her mother’s, becomes a site of abuse and disillusionment.

Romola’s death, shrouded in mystery and violence, haunts the narrator. The parallels between Romola’s life and her own become impossible to ignore—both women trapped by circumstances, both struggling to assert their identities in a world intent on erasing them. In the end, Romola’s absence looms large, a reminder of life’s fragility in a place littered with graves and missing faces.

In all these stories, Assam is not just a setting, but a character – brutal and beautiful – shaping and reshaping the lives of those who inhabit it. Fortunately the State also engenders voices like Goswami’s – razor-sharp and unflinching in their exploration of this vibrant and tumultuous region.

References

Uddipana Goswami, The Women Who Would Not Die: Stories, Speaking Tiger, 2024