Withstanding the Ravages of Love and Life

Namita Gokhale is unafraid to break story rules. In a fleeting meta moment, she acknowledges her distaste for bow-tied endings: “My quarrel with the short story is precisely that it imposes a false order and symmetry on events, forcing impressionable young minds to anticipate a similar state from the inchoate mess that is life.”

She can do this, of course, because her prose exudes a slickness, a deft dipping into and out of profound themes: love, loss, grief, memory, parenting, identity. Of the aggravating and also soothing intertwining of past, present and future. Like the Himalayas that she sometimes hovers over or meanders inside, her characters absorb life’s seasons, tucking each passing day or event into the folds of their being.

A Revised Take on Life

In Love’s Mausoleum, a divorcee who had trained herself to overlook her husband’s affairs, slights and betrayals, was taken aback when he asked for a divorce. He was ultra-rich and gullible, a philanderer trapped by the honeyed charms of a money-grubber. With her bitterness curdled inside her, she’s compelled to visit the Taj Mahal, the famed monument to love, while ashen memories swirl inside. As a historian, her mind wanders into the unstated crevices of Shah Jahan’s much publicized obsession with his wife. She wonders, as any woman might, about their sex life. And if Mumtaz really relished being constantly pregnant: “Seven living children, seven dead, in twenty years.”

The protagonist is childless. She thinks too, that their marriage would have held together – however tenuously and falsely – if they’d had kids. Though the infertility was her husband’s, she can’t help shouldering remorse. And a grating guilt.

Such grey thoughts, however, are broken on the drive back to Delhi. By another sudden memory. As a young child, she had learned classical music from Ruma Devi, an aristocrat who had brazenly gleaned “thumris and dadras” from prostitutes. Copying her Guru, the protagonist had absently smiled at the shriveled tabla player. When the Guru left the room, the man pounced on her, planting an unwanted kiss on her confused lips. She had felt culpable and complicit. And like many children, tormented by imagined fallouts. That she might get pregnant, that she might infuriate her parents.

She realizes now, with razor-sharp clarity, that it wasn’t her, but him. She wasn’t the perpetrator, he was. She was a victim, as she had been too of her husband and his doting mother. Symbolically, a rainbow glistens across the sky. Sometimes that’s all it takes for the clouds to give way and a new self to shine through: a shift in perspective. Not a schooled looking away but a compassionate looking at.

Among Riverine Twists

Vatsala Vidyarthi is both a “literary” and a “literal” lady. When she’s dispatched to Rishikesh by her advertising agency to discover “real India”, she also finds a man. And herself. All this while peddling an incense-cum-mosquito mat. With a keen sense of how things can be simultaneously tragic and absurd, surreal and humdrum, Gokhale observes how the sacred river is harnessed by marketers: “The Ganga, which had already endorsed products as diverse as soap and mineral water, remained for her the river of her childhood samskaras.” So yes, the multipurpose mat too, is named “Ganga.”

Overtaken in the pilgrim town by a Slavic stranger, Vatsala senses that she has forged a “cosmic” and otherworldly connection. Except that she wakes up naked and to the stark emptiness of her purse. She’s been robbed. Was that all it was, her desires succumbing to a lustful opportunist? But before you sigh for her shattered trust, read on. Gokhale engineers bends and twists that mimic the sinuous Ganga, depicting how hope can eddy into unexpected spaces.

Misplaced Compassion

The Day Princess Diana Died has a Delhi lady frankly acknowledging that perhaps the world is making too much of a fuss. After all, Diana was just one more human being whose life was snuffed out on that day. She was striking no doubt, a real princess who was princess-like, but should this evoke grief in cities as distant as Delhi, among folks who only knew her as a magazine cutout or television image? Yet, when the narrator is remonstrated for her lack of compassion, she notes how their apartment liftman has also died. When she tries to raise money for his family, no one seems to care.

Confronting the Roughs of Grief

In The Habit of Love, a young widow has to confront her past even as she shepherds her two daughters over a vacation in the Himalayas: “The past inhabits the future just as the future looms over the past.” As her daughters spot and rename constellations, she journeys through a rougher terrain, wrestling with internal demons. Eventually reaching that point of self-awareness, which can lead to catharsis or a tiding through: “The name of the mountain was grief.”

Epic Lessons from Life

The narrator in Whatever is Found in the World starts translating the Mahabharata. Only because she wants to give her life some structure. She’s afraid of collapsing into midlife nothingness, without some purpose that would infuse her days with a thousand tiny tasks, without some large project looming. While she’s not a Sanskrit scholar, she appreciates its precise grammar, noun declensions, verb conjugations and eight cases: “The greatest philosophical truths can be assimilated with startling brevity in Sanskrit.” Then there is the Mahabharata itself, the ur-Text with its universal conceit: “Whatever is here can be found in the world. What is not here will not be found elsewhere.”

Nonetheless, she abandons her translation while drifting from her British archeologist boyfriend to an older man she meets on an alopecia support group. While almost tiding through Covid together (spoiler alert: he doesn’t survive the pandemic), she emerges with new insight: “If true love is trust, if true love is understanding, I had found it in this world with him.”

In a collection that also wanders into the inner life of a stone, Gokhale shows us that love, loss, grief, repentance, the sturm and drang of human existence will endure. What we might yearn for in an age when billionaires plot their escape to Mars are earlier times when “humans knew the silence of stones and could listen to their wisdom.”

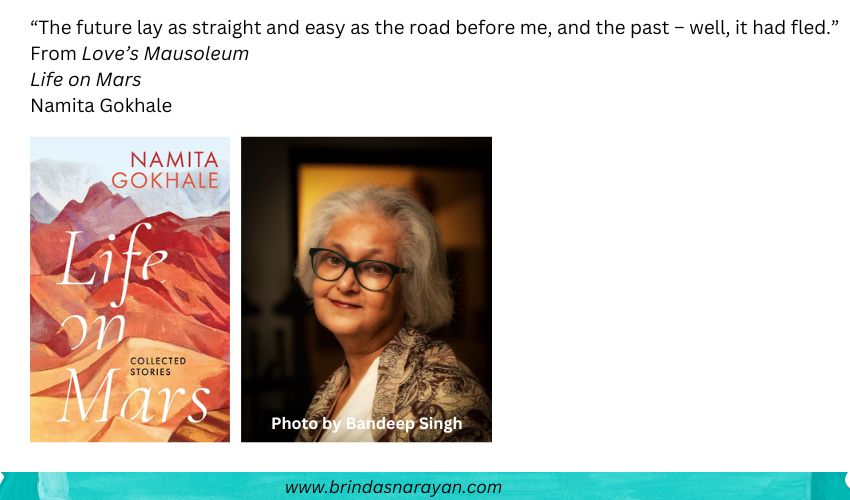

About Namita Gokhale

Gokhale has penned many works after her startling debut, Paro: Dreams of Passion. She won the Sahitya Akademi Award in 2021 and the Sushila Devi Literary Award in 2019. She’s also a co-founder and co-director of the marquee Jaipur Literature Festival.