India’s National Anthem: Its History

The oldest national anthem in use today is “The Wilhelmus” of the Netherlands. Though Jana Gana Mana was adopted more recently (in 1950, to be precise), it’s more widely known. It might even feature as the globally most popular national anthem. To begin with, it’s sung by the immense swathe of voices that people our nation. It’s also played across the globe, at events organized by our scattered diaspora, its familiar strains evoking our lofty peaks, glistening waterways and shiny seas.

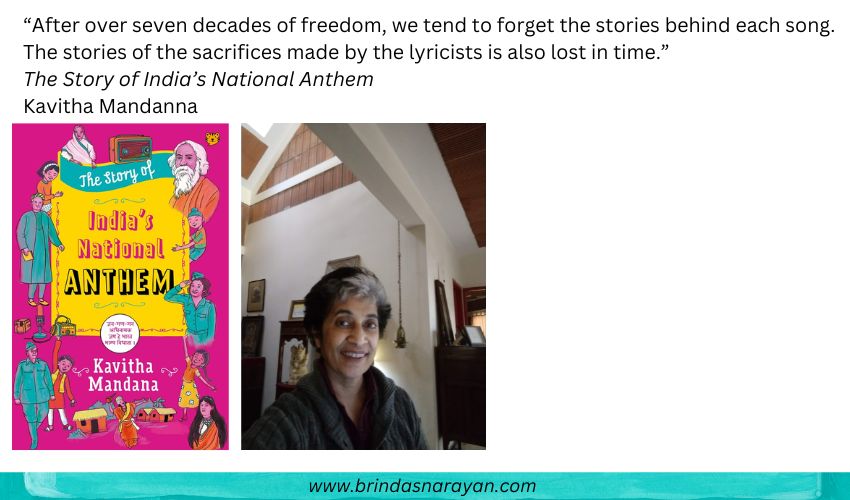

The adoption of this particular song wasn’t a given. In The Story of India’s National Anthem, Kavitha Mandana traces its origins and stokes a curiosity about our past in young adult (and adult) readers. What are some little known facts that one can glean from this book?

While many boomers and Gen Xers might be familiar with Rabindranath Tagore, I’m not sure if he’s accorded the space he deserves in school history lessons. While there are many reasons for why he should loom in the national imagination, perhaps one of the many pronounced ones is that he penned our anthem. And fashioned its transcendent plea, mirroring the philosophy that underscored his life and work.

Since he died at the age of 80 in 1941, he didn’t live to see the country achieve independence. Nor did he know that his song was later adopted as India’s anthem. Perhaps none of this would have mattered to him. What he might have desired fervently was for his universalist, humanistic vision to seep into every heart.

A Short Sketch of Tagore’s Life

Born in 1861 in Jorasonko, Tagore belonged to a well-off, aristocratic family. His grandfather, Dwarkanath Tagore, had veered from the pathway of his caste (they were Pirali Brahmins, a subcaste of Brahmins that were associated with a Muslim fakir) to become a businessperson. Cleverly partnering with a Britisher, he was an equal partner in Carr, Tagore and Sons. As a mining and shipping magnate who also ran huge estates, he lived a lavish life and even met the Queen.

As the 13th of 14 kids, Rabindranath was particularly drawn to nature, preferring to spend time at Shilaidaha, one of the family’s properties surrounded by acres of green. He composed many of his stories and poems here while contemplating its murmuring, tree-laden vistas. Needing to stay in touch with a host of people, he often wrote letters. And frequently encountered the village postman, Gaganchandra Das, a Baul musician, singer and lyricist. Recognizing the postman’s talent, Tagore even published many of his compositions in the family’s newsletters and magazines.

Though Tagore was knighted by the British Empire, it was an honour he returned after the horrific Jallianwalah Bagh massacre. In 1913, he was also the first Indian to be awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature. Bizarrely, no Indian writers have been awarded the prize since, a void that highlights the unfamiliarity of the Nobel jury with the riches embedded in our various languages.

A Divisive Law Fuels Two Tagore Songs

In response to Lord Curzon’s infuriating “Divide and Rule” imposed on Bengal in 1905, the Congress launched the Swadeshi movement. Non-violent and violent protests erupted across India. A stirred Rabindranath wrote “Amar Sonar Bangla” – a moving ode that emphasized the commonality between Bengalis, the shared heritage and beauty of their tidal State. With a porous, fertile mind that could draw inspiration from any source, he chose to set Amar Sonar Bangla in tune to one of the Baul postman’s compositions. The first 10 lines were to be adopted by Bangladesh as its national anthem in 1971.

Congress was planning a Committee meeting in Calcutta to pressurize the British to roll back the partition. In 1905, Rabindranath Tagore had published “Bharata Bhagya Bidhata” in his father’s newsletter, Tattwabodhini Patrika. The song endorsed Tagore’s belief in a people’s victory, in a force more powerful than the divisive British that could unify the nation. His niece, Sarala Devi Choudhurani, set it to music and trained a group of students to sing it.

Tagore called “Bharata Bhagya Bidatha” the “morning song of India” as he felt it heralded a new phase in the freedom struggle. It was translated into English and performed again at a Congress Committee meeting in 1917.

An Ill-Timed Crowning

In December 1911, Viceroy Harding had to contend with targeted killings occurring across India. In the midst of all this, he chose to organize the Delhi Durbar, to crown George V and his wife, Mary, Emperor and Empress of India. Unlike in previous Durbars, this time the Royals wanted to show up in person. A temporary tent city was erected in Delhi. While all princely rulers attended the controversial crowning, Gopal Krishna Gokhale and Bal Gangadhar Tilak expressed their dissent by boycotting it.

In December 1911, George V announced that the Bengal Partition would be rescinded and that the capital would shift from Calcutta to Delhi. In a ceremony to ostensibly thank the King, a school choir sang “Bharata Bhagya Bidatha.”

Vande Mataram As a Close Contender

In 1905, after the British had partitioned Bengal, people started singing Vande Mataram as a protest song. Especially on college campuses. Moreover, people were reading the serialized version of Bankim Chandra Chatterjee’s Anandamath. That story spoke about how some warrior monks defied British soldiers by bellowing this song. The British were so shaken by this, that RW Carlyle, the Chief Secretary banned the song with a “Carlyle Circular” – but students and the public continued to sing it. If students were expelled from British institutions, new swadeshi schools and colleges welcomed them. “Who would have imagined that a song embedded within a larger work of fiction would have the power to rattle the British?”

Subhash Chandra Bose’s INA movement preferred to sing Vande Mataram, but this did not appeal as much to Muslim and Sikh soldiers. Lakshmi Sehgal, head of the women’s wing in the INA suggested the more syncretic “Jana Gana Mana” and Tagore’s Bengali original, translated into Hindustani, became the INA anthem in 1943.

Eventually, on 24th Jan 1950, Rajendra Prasad chose the Hindi translation of Tagore’s song as India’s anthem.

Voices Cannot Be Confined

Before it was sung anywhere else, “Jana Gana Mana” was first sung in Doon School in 1935. The school itself was founded by Satish Ranjan Das, and was meant to be modeled around Eton and Harrow in the UK. Rabindranath Tagore was not a huge votary of Doon as a concept, since he felt it was too elitist.

Mandana’s deft work, illustrated by Dhwani Ved, also touches upon the advent of the phonograph and the manner in which Tagore’s own singing of Vande Mataram was captured on it. Or of the Congress Radio, which started broadcasting from 1942, beaming songs like Vande Mataram and Saare Jahaan Se Achcha to millions of Indian listeners. Just a week before the first radio broadcast, Gandhi had addressed a crowd at the Gowali Tank Maidan at midnight. He was soon arrested and thrown into the Yeravada jail. But the British couldn’t stop his voice from reaching millions just a week later, on radio.

This book is a reminder that poems and stories, art and music matter. They have been and always will be the means to overcome seemingly intractable forces. As the author reminds us, Tagore was the instrument through which our national anthem billowed into being. The poet elegantly phrases this in The Gitanjali, “This little flute of a reed thou hast carried over hills and dales, and hast breathed through it melodies eternally new.” Tagore is long gone but his song and its message will forever resonate.

About the Author

Kavita Mandana has penned several children’s books. Her short stories have appeared in anthologies and in textbooks. Her writing and illustrations have featured in the Deccan Herald children’s supplement.

References

Kavitha Mandana, The Story of India’s National Anthem, Talking Cub (Speaking Tiger), 2025

Thanks Brinda… for this great write-up!

Regards,

Kavitha