Transforming India’s Art Scene: Abhishek Poddar’s Journey to Founding MAP

In the throbbing, trafficky heart of our city, history and creativity collide. From ancient sculptures and textiles to modern paintings and pop culture treasures, the Museum of Art and Photography (MAP) has it all. The sleek steel facade with its embossed cross pattern spans six floors. Step inside and you’ll find galleries, cool digital experiences, a research centre and conservation lab, plus spots to shop, sip coffee, and dine on a rooftop with a killer view.

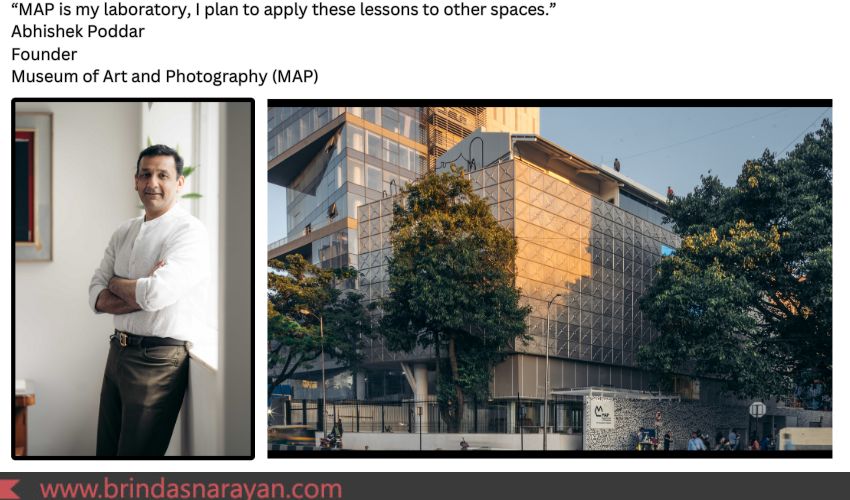

A hub for ideas, stories, and culture, MAP ignites empathy and understanding in a world that needs both. Chatting with Abhishek Poddar, the founder of this iconic space gave me insights into how his striking vision was sparked during childhood.

Early Creative Influences

Poddar’s affinity to art was seeded early. His joint family home in Kolkata – teeming with aunts, uncles and cousins – sputtered with celebrations and a stream of intriguing visitors. Classical musicians like Kumar Gandharv, Pandit Jasraj and Ravi Shankar spun their magical ragas within those walls. Which were hung with the paintings collected by erstwhile Bengali Zamindari households.

School-going Abhishek had his own opinions on those works: he didn’t quite relate to them completely. Instead, his eye was riveted by The Illustrated Weekly centerspreads, that featured Indian artists in quirky poses or performing bizarre acts, “with paint on their faces, jumping shirtless”. Soaking up their names, oddball lifestyles and distinct takes on the world, Poddar was speechless when he encountered a lanky, bearded gentleman 200 meters from his home. Looking down to confirm his hunch, 15-year-old Abhishek realized he was staring at India’s most famous barefoot artist: MF Husain.

Striking up a friendship with the painter, who stayed at his home many times thereafter, Poddar even painted a few pieces with him. It was Husain who proposed they paint together. Unfurling a canvas, he encouraged Abhishek to join him while he applied his signature brush strokes. That joint artwork, co-signed by the legendary artist and his teenage admirer, hangs in Poddar’s office today.

Forging Friendships with Master Artists

While he was a student at The Doon School, on a trip to Delhi, he visited Manjit Bawa’s studio at Garhi. The artist was not there, so Abhishek left a note for him. And dropped in again on a future visit. Coyly mentioning his earlier note, Poddar, still star-struck, engaged in a polite tete-a-tete with the master figurative painter, calling him “Bawa-Saheb”. At one point, Bawa interrupted him with: “Call me Manjit.” Abhishek demurred. Bawa was almost his father’s age, and a revered artist. Eventually, he proposed a mutually acceptable “Manjit Bhai.”

“Then suddenly he stood up and I thought he’s going to do something or show me something. But he just kept staring at me for 5 seconds, 10 seconds, 15 seconds, it must have been half a minute. So I said, ‘what’s the matter?’”

Bawa said if he was going to be called a “bhai”, they ought to embrace like brothers. And embrace they did. Abhishek invited him to his home in Kolkata. The very next weekend, the guard at home insisted he had a visitor. Poddar thought it must be one of his father’s many guests. He realized soon enough that Manjit had acted on his invitation, maybe to test his sincerity. They spent 2 ½ days together, talking art, roaming the city, visiting galleries and artists. At the end, Poddar asked him to return. He did again, the very next weekend.

Canteen Cravings to Creative Getaways

At Doon, Poddar’s flirtations with art inspired a different, roguish scheme. As boarders, he and his friends were always hungry. Desultory canteen foods could hardly fill their appetites. He noticed that some boys were merrily leaving the campus. He discovered that they were involved with the school magazine and were supposedly heading to the printer’s. Hatching a crafty means to imitate that bunch, Poddar proposed to start an Art Magazine. Persuading a somewhat unsure Headmaster, soon Abhishek and his “bhuka friends” were tripping frequently to the “printer’s” – to theatres, restaurants and pubs – till the year-end deadline loomed.

Hurriedly dispatching letters to ten of India’s greatest artists, they requested responses to print in their issue. Only one artist replied. As the D-Day approached, the Principal announced that Rajiv Gandhi would be visiting the school and launching the Art Magazine. Abhishek chuckles when he recalls the four-letter expletive that must have crossed his lips. When they had just a page left to print, they received eight artist responses. Pinning those letters as a backdrop to the launch, Poddar salvaged a thorny situation.

Unpacking Art’s Elitist Aura

Later, in life, while also heading businesses, he continued his dalliance with art, garnering pieces without intending to be a “collector.” Drawn to the works of various contemporary artists, he realized he had built a fairly large collection by midlife. On trips abroad, he noticed how large and small museums attracted large crowds with well-explained, thoughtfully curated exhibits ensuring a delightful experience. Typical Government-run Indian museums lacked the same appeal. As he puts it: “They had incredible collections, but the experience was underwhelming – poor lighting, incomplete signage, incorrect explanations, and sometimes, even dead cockroaches in display cases.”

In the meanwhile, the nation’s capabilities were being showcased in other spaces: in swanky airports, metro stations, designer hotels, snazzy malls and hip restaurants. Why, wondered Poddar, were museums lagging behind? He had also noticed another troubling trend. Even as the Indian art market spiraled to giddying heights – with some art works being auctioned for outlandish sums – ordinary folks felt alienated from art. The art world had started acquiring an elitist aura, which only the moneyed or the knowledgeable could inhabit: “You either have to be a millionaire or an art historian or critic.”

Mainstream media no longer featured artists and their works as prominently as The Illustrated Weekly, Sunday, Outlook and India Today once did. In spaces like the Louvre or the Tate Modern, bus drivers and school teachers stared at the Venus de Milo or at Warhol’s Marilyn Monroe, without being fixated on the zeroes the works would fetch. Why couldn’t Indians access their rich artistic heritage in a similar manner?

Creating Virtual Museum Magic

Determined to play an active role in creating a public space where art could be enjoyed by all, Poddar eventually settled on founding MAP, which also required substantial investments from him and supportive patrons to acquire land, construct the building and showcase collections inside a thriving, animated place. Naturally, in such an endeavor, obstacles surfaced from the outset. Their launch had been scheduled for December 2020. March 2020 brought Covid and the world-wide shutdown. With the pandemic lingering, they pivoted to a digital launch.

While Poddar himself had only a skeletal understanding of technology, he quickly leveraged the city’s coding smarts. The CTO jokes that he was elevated from his basement workstation to a corner office. While talking to a technologist friend, it struck Abhishek that a Zoom launch or webinar-style event would slide into the stale heap of similar dos. Digitally ushering visitors through the rooms and corridors of their would-be museum could attract eyeballs. And it did. While a physical launch could have hosted about 150 people in the air-conditioned auditorium, MAP’s digital launch drew 30,000 viewers from across the world.

Democratizing Art with Fun

Abhishek also observes that his lack of experience in the museum-making space spurs a fresh take. Rather than making it stuffy or pedantic, Poddar and team infuse it with pep and fun, without compromising on depth. Exhibits range from the serious to the playful, including for instance the history of Bollywood posters. Folks who missed a previous exhibit can access past exhibits with the click of a button. Their rooms are bereft of stern “Do Not Touch” signs. They deliberately feature some works that invite tactile interactions. Fostering cool fusion between art and technology, they create experiences that have never been tried elsewhere. Whenever someone approaches Poddar with an idea saying, “So-and-so has done this –” he responds with: “Why replicate it here? We should do it better and differently!”

While tickets are priced reasonably for the middle to upper-middle classes, they heed the millions at the bottom who would need an even lower rate: Zero INR. They’ve incorporated a free day every week, and Poddar has watched village folk, autorickshaw drivers and delivery persons come into the artsy castle – exactly as he hoped they would. To emphasize the democratic nature of the space, soon after opening the physical building, Abhishek invited the construction workers and their families to be their first visitors.

And accessibility? They’ve nailed it. The building, designed by Mathew & Ghosh, makes art available to all, including folks with disabilities.

Fostering Creative Collaborations

MAP also currently collaborates with top museums in other parts of the globe. They’ve hosted joint exhibitions, co-curated displays, crafted a series called “Director’s Cut” in which museum directors engage in conversations about the art world and Insider’s View, which offers private tours of special exhibitions in foreign locales. “By collaborating, we’re not just sharing art digitally; we’re also training our staff through programs with institutions like the British Museum and the MET,” Poddar explains.

Besides the museum, the team has also created the MAP Academy, the first comprehensive encyclopaedia of Indian Art, free courses on Indian classical and contemporary art, sculpture, photography and textile heritage among a plethora of topics. They’ve attracted more than 50,000 visitors each month, indicative of the thirst for knowledge about Indian art and photography.

Pushing boundaries – whether in their displays, or in the use of technology or in collaborative storytelling – seems to be working. They currently draw 8,500 to 10,000 visitors a month, with most attendees belonging to younger cohorts. He laughs: “Sometimes, I’m the oldest person there.” The interest being stoked among GenZs and younger is important to Abhishek, because the intent is to foster a museum-going culture in the country.

With MAP being a “laboratory” of sorts, Poddar hopes to take the lessons from this experience into other spaces. Like into Government museums, which can be revived with private partnerships and a contemporary, design outlook. When asked if Government museums would be open to receiving such help, he shrugs: “Maybe not, but why should that stop us? You just barge in and get it done!” Unwilling to take “no” for an answer, he intends to keep knocking on doors. He’s aware that private museums can only go so far, and it’s the Government that can engender scale. “I can’t change the country by doing it all myself,” he says, “but whether you coax, cajole, beg, plead, educate or even shame or scare them into action—whatever works—you’ve got to get the Government on board if you want to make a real difference.”

References