The Seductive Perils of Time Travel

In earlier eras, those who crossed oceans to ‘discover’ new continents or forge trade linkages were exalted as adventurers and risk-takers. It takes, however, a different kind of courage to journey into one’s own consciousness, to exhume the past and imagine the future, till the present assumes the surreal fleetingness of a dream. For a few who do this with a scalpel-like acuity and never-say-die persistence, they might as the scriptures promise, cross over : transcend the mundane tugs of time and space, encountering and re-encountering past and future selves.

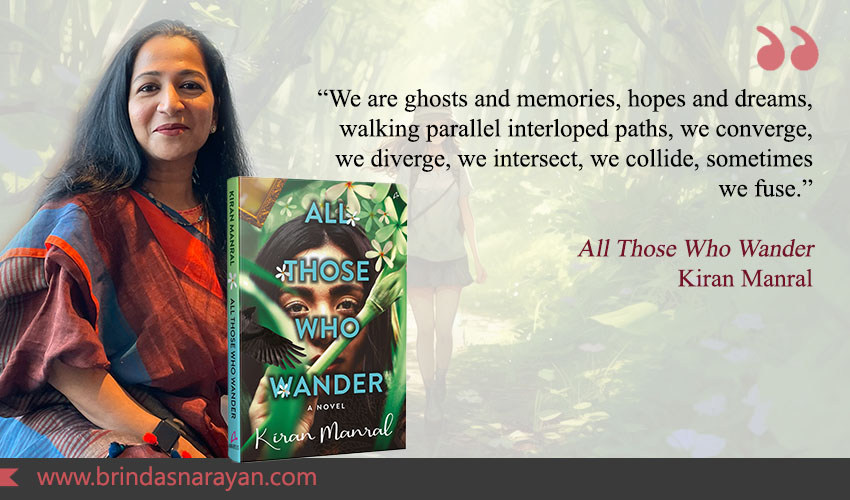

In All Those Who Wander, Nayna is born with that gift, or if you put it another way, that curse. That ability to hurl herself – usually by staring at her own reflection in a mirror – and meet with Ana, her future self who wraps her frailties in a seemingly thick hide, who floats in a seductive ether untouched by societal mores.

Or maybe it’s the other way around. It’s not nature, but nurture: it’s not Nayna who travels into the future, but Ana who visits the past. She had, after all, been groomed into that kind of life. To shun mainstream tugs after witnessing the dissolving of a dead marriage, with the only kind of exit that her father could conceive of: by jumping off the terrace to his sprawling end, urging his slip of a child to follow.

It was a command that Nayna did not heed, but it was a scene she would revisit, again and again, wondering how everything might have turned out if she’d obeyed. Or what if her parents hadn’t been bitterly feuding all along, driving the pensive, dreamy Nayna to commune with her favorite friends: the Crow or Dog. Or with other dead people. Ana, like any adult who has had a traumatic childhood, revisits the trauma on a repeat-loop. But her time-traveling ability also permits her to re-enter the past and alter it.

With chapters intentionally organized to diffuse like a dream, with scenes segueing into each other like waves, with overlaps and retellings of the past, with ever-so-tiny or large shifts in the sequence of events, this is a story that washes into you. And tugs you into the tidal eddies of Ana’s life, into memories scarred by the embittered and always-enraged mother, who “hated touching and being touched.” Then again, Mandira (Nayna/Ana’s mother) has a past too, and you empathize with her lifelong resentment, her confinement inside a box-like public sector flat, her understandable chaffing against a hastily conjured marriage to a repulsive man.

But the repulsive man is a good father; maybe even a kind soul, who fathers a daughter who isn’t really his, with seeming affection. Who wants to ferry her along on a final journey, away from a mother whose rage coils inwards and outwards, her words always lashing or hissing.

Manral is a lyrical writer. Her descriptions of India past and present, of Mumbai and Bombay, might have felt longer if handled by someone who lacks a similar deftness with words. By inhabiting the poetic Ana/Nayna, whose ongoing sadness is not just plaintive, but strangely melodic, Manral paints even the drabness of a Mumbai housing society with vivid strokes. In, “the incestuous cauldron of crumbling four-storey buildings hiding crumbling lives, fading hope and diminishing dreams,” residents come “from all over India, from the small towns of Bihar, from the paras of Kolkata, the mofussil towns of the Gangetic plains, the earnest academic homes of South India…”

In Einstein’s Dream, the MIT physicist Alan Lightman bends time into different shapes. Into a circle or a stream or a jumble, where effect precedes cause. In a similar manner, Manral tosses time, making it sometimes sticky, and sometimes so frolicky, it can be flicked aside as one would a single moment. After all, if time isn’t the tedious linear march that we’re all conditioned into experiencing, everything becomes weightless. Including, or especially, man-made sorrows.

Acutely aware that all the women in her book are subject to patriarchal terrors – the mother, Mandira having been forced into an unhappy marriage, compelling Ana to live with an unhappy mother, and then be confined or liberated by her lover – Manral robs time of its gender-neutral quality. Because time, like space, acts differently on different people. And since women have usually been more curtailed – inside kitchens, in drab flats and domestic lives – they cast away the only dimension that feels occasionally pliable.

As women (or others at the bottom of any hierarchy) know, time crawls for those who are physically or psychologically imprisoned; or sometimes does exactly the opposite. Speeds up when days are a blur, when one week follows another with metronomic predictability. Fortunately, for Ana, there’s another Greyness that she can leap into. An in-between space that might await all or any of us, if we look deeply enough at ourselves.

All Those Who Wander is a reminder that adults do not have to forgo the magic that might have led their child-selves into secret gardens. As Ana reflects, “We were doomed to forget magic and lose our belief in it as we became adults.” Fortunately, as Manral shows, that’s not true of all grownups. Investing her tale with Borgesian make-believe, she depicts how fluid and dismissible everything, everywhere actually is. Not just societal mores but even the laws of physics. If you stare long enough at a watery mirror – like in that teachy Greek tale – you might be yanked in by the very being you love or detest the most.

References

Kiran Manral, All Those Who Wander, Amaryllis (Manjul Publishing House), 2023

One thought on “The Seductive Perils of Time Travel”