Chemicals and Basketball: Navigating Identity in Appalachia

Neema Avashia grew up in an America that wasn’t typically inhabited by folks like her. West Virginia wasn’t where most Indian Americans headed. Asians constituted a miniscule 0.5 % of the population in a state that birthed televangelists and country singers. Quite inevitably then, her family abided with the palpable dread of a targeted, suspected minority. Their jitters ballooned after 9/11. So much so, that her father affixed a “giant American flag” on their door.

She was never sure if such signs of belonging were quite enough. After all, she herself had been slapped as a kindergartner: “…in West Virginia there were only two categories that seemed to matter when it came to race: White and not White.” This did not mean that relationships were perennially fraught, or precluded intermingling between races. In large part, her family had woven itself into the fabric of the region, living inside a gated neighborhood that housed the managerial staff of chemical plants. Her father was a doctor employed by Union Carbide, and fondly called “Doc” by friends and neighbors.

Loyal to Chemicals and Community

“Doc” had grown up with a reverence for chemicals. Posted as a young medic in an Indian village, he lacked the means to buy anti-rabies shots to treat bitten villagers. Rather than helplessly watch patients foaming at the mouth, then die in a ghastly manner, he laced milk bowls with arsenic to kill village dogs. By her father’s ethical reckoning, humans versus dogs wasn’t a debate. So it was with other chemicals: DDT to vanquish malaria-carrying mosquitos, pesticides to save crops. As Avashia puts it, in her father’s worldview, “Chemicals prevent illness. Chemicals spur our nourishment. Chemicals save lives.”

Her father had a short fuse but was also “generous, and neighborly.” For instance, he’d cart back free prescription meds from India, where drugs were cheaper, to dole out to needy folks. Or conduct free physical exams on all kids on his street. He might have been breaking some rules in doing all this, but as a result, Avashia gleaned that he had an “ethics of place.” Which was not so much about “rules” but about the consequences of actions.

In 1984, when Union Carbide had to rapidly respond to the Bhopal gas leak, her father was dispatched as part of the “crisis team.” He was the global face of the company during one of the worst humanitarian disasters ever. And forced to defend his American employer against the barrage of infuriated attacks from Indian media and Bhopal’s hapless victims. As Neema observed, “he sided with the company that signed his paycheck over the country of his birth.”

Voicing Principles as a Teacher

Avashia also practices an ethics of place as a teacher in Boston, where she’s more involved in the lives and trajectories of her school students than most educators would be. Till 2013, she was a kind of model teacher and teacher trainer. She was even recognized as one of “Boston’s Educators of the Year.”

Appointed to a more influential position in the superintendent’s team, she was privy to budget cuts that would damage critical programs. In the Arts and Special Education, for instance. When she spoke to a newspaper about this, she was given a warning: unapproved interactions with the media could lead to her firing. She did not relent and complained to the Teachers’ Union, whose leader then contacted The Boston Globe. Marked out as a trouble-maker, she found the Committees more responsive to her demands. Unlike her father, she realized that one did not always have to align with one’s employer to gain power.

She and her father have rarely had emotional exchanges. Usually, their interactions have been transactional. When she tries to write scenes that involve her father, “I see him in monologue: My dad speaking, me listening…”

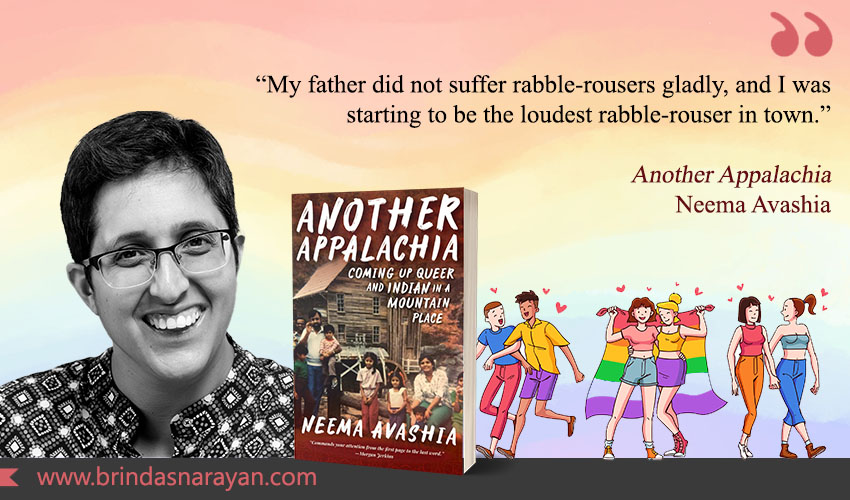

Her father still has an absolutist’s faith in chemicals, as she does in education. In 2018, when her school faced closure, she protested loudly and dramatically. “My father did not suffer rabble-rousers gladly, and I was starting to be the loudest rabble-rouser in town.” Of course, she’s also aware that her own privilege (earned by her father’s faith in chemicals) imbues her with the courage to speak up for her disenfranchised students. Conscious that she too is implicated in her father’s past, she leverages her voice for student issues that need her support.

Throwing Basketballs Underhand

When Avashia was a child, her immigrant parents did not understand basketball. They did not see the need to support her game. But Neema tried out anyway, despite being gawky, short, and the only girl in an all-boys team. She’s grateful that her coach Mr. Bradford picked her and took a particular interest in her game. Since there was no way she could land the ball in a basket by throwing overhand, he suggested she try it underhand. Her teammates mocked her, calling it “Granny style.”

Basketball was a means to enter the mainstream culture in Virginia, an attempt to forge a belonging. She was reluctant to try the underhand shot however, reluctant to stand out in the way she played the game. After all, the whole thrust behind her playing was to stop standing out. Once, in the heat of a real game, she flung the ball as instructed and scored two dizzying points. The crowd erupted in a cheer, chanted her name. She experienced a heady success. Mr. Bradford had her in his team for three years, then recruited her as an assistant coach for younger teams. Riding in his jeep with other team members made her feel more American than any other experience could have.

Grappling with Red/Blue Divides

Most people have left the place now. There are hardly any friends and neighbors left. The few who are around seem to be old and dying. Just like the neighborhood, with many windows boarded up, flaunting “For Sale” signs, the grass erupting between gaps in the concrete.

She confronts a political divide between people she loved as a child and still does as an adult, while contending with their disparate and rather shocking political and social beliefs. She had always deemed of a certain White West Virginia couple as her own grandparents – a Mrs. B and a Mr. B. Now she watches the old Mr. B spew hateful invective on FaceBook, with racist, anti-immigrant messages, and she wonders if he ever thinks of her or her family when he posts his views. On the other hand, she still loves visiting him, drinking sweet tea in his house. She can’t forget how Mrs. B, who died of cancer, had fed their family specially-cooked vegetarian meals every month. Mr. B has always been loving and polite to Neema.

But she doesn’t dare come out in his presence, doesn’t introduce Laura as her partner. She’s appalled but also understands how West Virginia was once a blue state and has now turned red. After all, the economy has been hollowed out after many chemical companies shut down. The past does seem greater in these states. She empathizes with the anger of current residents. But she can’t endorse their homophobic, racist, Trump-thumping views. She learns, like most West Virginians, to stop discussing politics when it’s uncomfortable.

Another Appalachia brings to light an Indian American experience that is unlike many set in the East or West Coasts. Immigrant narratives are often entangled and knotty, but Neema contends with the added complexity of growing up queer in a place that seems to have few people like her. This perhaps is the best part: she does not write with anger or denigration, but with generosity and grace that we, as readers, would do well to imbibe.

References

Neema Avashia, Another Appalachia: Coming Up Queer and Indian in a Mountain Place, West Virginia University Press, 2022