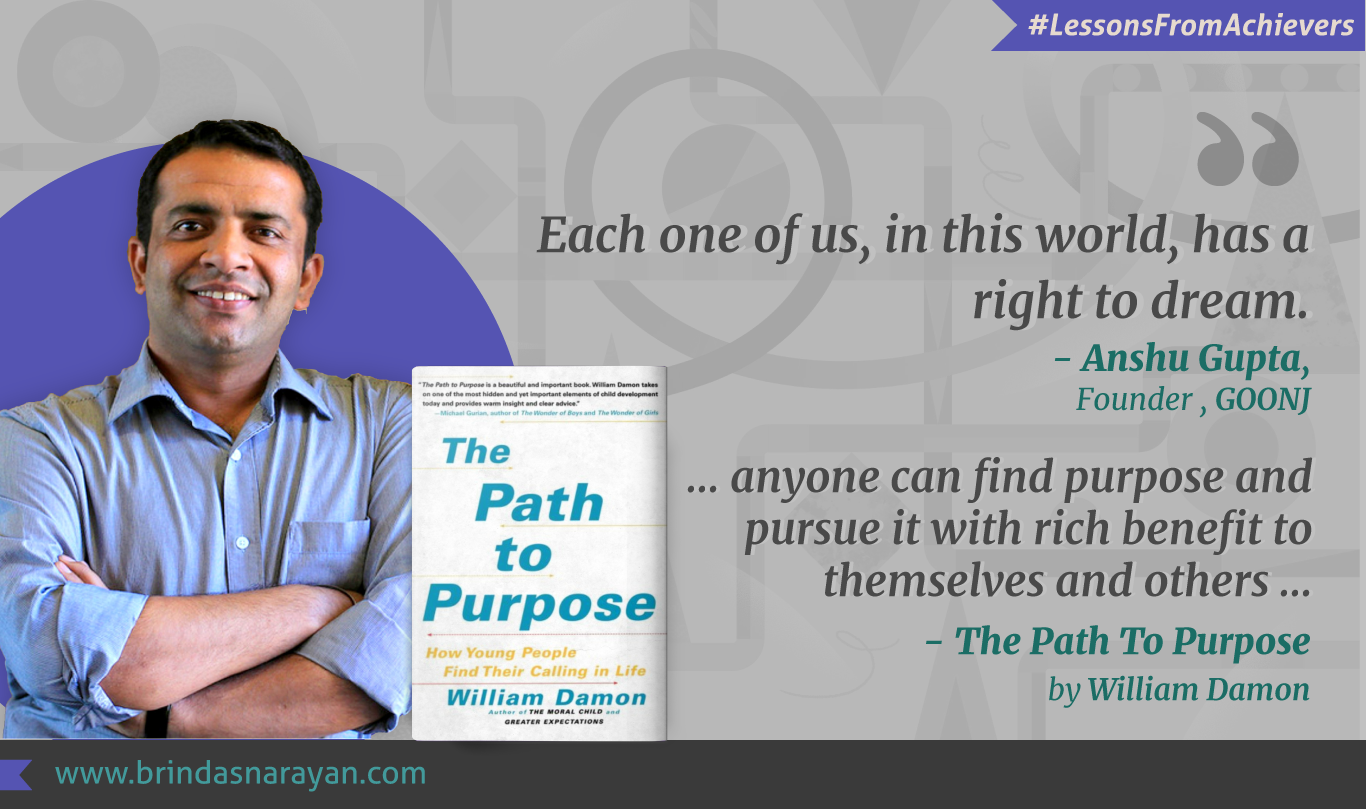

Anshu Gupta, Founder of GOONJ, Charts a Purposeful Life

Anshu Gupta: Brought Up With a Social Conscience

Well before he was on his path to forging rural-urban interactions and the kind of straddling across socio-economic classes that the country desperately needs, Anshu Gupta, the founder of GOONJ, had started formulating his own notions of human dignity. Born in Meerut, Uttar Pradesh, and as the son of a Government Officer on a transferable job, he grew up in the “smallest possible places.”

Like in Banbasa, a town, which as per the 2011 census, had a population of less than 8000 people. Situated in the midst of dense jungles teeming with wildlife, the town had many of its people residing in its forested peripheries. Another place, Chakratha, was stippled with conifer trees and exuded a hill-station’s aura. But none of these tiny places featured on tourist maps, and so Gupta really had to rough it out in ways that kids growing up in larger, more endowed cities can hardly relate to.

For instance, in some of the schools that Gupta attended, there was no basic stationery or sitting mats even. Moreover, one had to always walk to school, since there were no other means of transport, or no motorable roads leading up to the school premises. Some of the barebones schools that GOONJ currently works with remind Gupta of his own spartan childhood.

One of the striking aspects of his early years was that, because of the compactness of the towns in which he was brought up, schools were less segregated by class than they are in larger places. So the boy who used to deliver milk at Chakratha was also a schoolmate. Moreover, his parents consciously modeled respect for people belonging to lower income groups. His mother, always deeply supportive of their own household help, served her staff hot tea before they started work. His Dad engaged with rickshaw-walas to drive improvements to their lives.

As a family, they also had to tide over trying periods. Despite such ups and downs, his mother emphasized the need to maintain one’s dignity. She said even if one possessed only a single knicker, one should wash and iron it before wearing it to school. The psychological imperative for each person to fortify his or her own dignity was to imprint itself in Gupta.

From The Path To Purpose: Many Young Adults Seem Adrift

In addition to ensuring his education and the cultivation of moral values, Gupta’s parents seemed to have fostered a social awareness that was to fuel his career later. Unfortunately, many young people do not seem similarly fired up by local or global problems that would benefit from their intervention.

William Damon, who is currently a Professor of Education at Stanford and the Director of the Stanford Center on Adolescence found a strange affliction among young adults and teenagers. A fairly significant number, despite being exposed to greater career opportunities than previous generations, seemed to suffer from a grievous apathy or disinterest. These included people who had successfully completed college degrees, but who then returned to parental nests (or not), and seemed disinclined to pursue any path that might lead to financial or personal fulfillment.

As Damon puts it, “disengagement or even cynicism has replaced the natural hopefulness of youth.” In a survey that Damon conducted among 12 to 22-year-olds, a quarter reported that they did not have any “aspirations at all.” As an example, one of his interviewees, who was a freshman at college, said: “I don’t really have goals for my future. What’s the big deal about that? It would be fun to travel. I’d like that, especially if I could get someone to pay for it.”

And this is not just an American phenomenon or even limited to a privileged set that might tend to feel entitled. The British Government even fashioned a term to describe the group: “Young NEETs” (“Not in Education, Employment or Training”). The malaise has been reported in many other countries, including Japan and Italy. Such widespread unconcern or listlessness has not even been triggered by a lack of economic opportunities. The overriding worry is that, in the long term, such drifting along without a strong sense of self-worth, can fuel anxiety and depression. As Damon puts it, “there is a powerful link between the pursuit of a positive purpose and life satisfaction.”

Anshu Gupta: Kick-starts GOONJ

While his upbringing might have been one of the factors, other experiences, consciously sought, also imbued Gupta with his life purpose.

As a post-graduate student at the Indian Institute of Mass Communication (IIMC) at Delhi, he was still tugged by his social conscience. In 1991, an earthquake ruptured the Gharwal and Uttarkashi regions in Uttarakhand. Thousands of homes were shattered and at least 768 people were reported killed. Instead of remaining inside the confines of his safe Delhi hostel, Gupta headed to the disaster site. This was, he says, his first real exposure to rural India, and to perilous mountainous terrains. But what moved him more than anything else, was the resilience and generosity of the affected. Despite being rendered suddenly homeless and surrounded by the shards of a previous existence, the victims were determined that the visitor from the city should not leave without a hot tea.

Around then, he was to encounter another sight that was to engender a deep internal shift. Habib Bhai was a rickshaw-walla in old Delhi, who used to pick up unclaimed corpses, of homeless people who had died in the extremely cold climes they were exposed to. Gupta spent ten days, immersing himself in the lives of Habib Bhai, and his six-year-old daughter Bano, who confessed that she sometimes had to cling to dead bodies in order to keep herself warm.

As a future journalist or communications expert, he felt deeply drawn to the story being enacted in his presence. Earlier, in Dehradun, he had not witnessed such poverty, such skeletal living on footpaths, the vagaries of migration, and so many uncounted deaths outside hospitals. He felt like he was witnessing aspects of the country in a way he hadn’t earlier.

After his IIMC degree, like most young adults, he headed into a corporate career. But by 1999, he felt like he had enough of the corporate world. For one thing, he was eager to shed his tie and black shoes. While he did have positive memories of his last organization, he felt his own talents were not being optimally leveraged. He then boldly decided to quit and start something else. He could have applied for other jobs, since his experience in the telecom industry commanded significant value. But he knew, in his case, such a job was unlikely to be fulfilling.

Besides, his earlier brushes with the street-dwellers continued to niggle. He wrestled with the unconscionable irony that someone in his position could spot, but rarely interrogated: that there are people with excess clothes and materials, and others in this country, who not only have too few, but are even dying because of a lack of blankets or warm layers.

He did not have any exposure yet to the social space or to NGOs. Like most salaried employees, he was unaware that a new organization needed to be registered first. Even as he started GOONJ as an informal outfit to distribute clothes from places where they were piling up as discards to areas pockmarked by scarcity, serendipitous forces seemed to aid his efforts.

For instance a friend visited his home, and asked him if he had registered his setup. The visitor, who happened to be a Senior Govt. Officer, asked Gupta to meet him the next day at his office. When he headed to his friend’s office, Gupta realized that his friend himself was the Registrar of Societies. Without wading through red tape, Gupta completed the necessary paperwork and got GOONJ registered as a formal organization.

Currently, GOONJ, which reaches into 27 states in India and employs about 1,200 people – some full-time, and some who work on a piece-rate basis – moves materials from spaces of surplus to places of scarcity. Comprising of a labyrinthine logistical setup, the organization has established collection centers in all major cities, and partners with several other NGOs and volunteer organizations to dispatch goods where they are needed most. Of course, the materials are filtered, cleaned, sorted and repurposed, ensuring that they are handed out in a condition that is always cognizant of the dignity of the recipient.

In return, people in rural areas contribute their labor towards solving their own infrastructural issues – which might include building roads, schools, wells, bridges, toilets or servicing some other local need. So far, their initiatives have culminated in several hundred infrastructure projects across thousands of Indian villages.

From The Path To Purpose: The Makeup of Purpose

When so many countries are in need of social entrepreneurs like Gupta, what accounts for the inertia or disinterest among so many young adults?

One of the contributors to this phenomenon can be high parental expectations, which compel kids and young people to overachieve in every sphere, and then to discover that colleges and workplaces are not as utopic as they were led to believe. As Laura Pappano, an education writer, put it in a New York Times article, “We are pushing kids to do so many things to get in, so what do you do when you get in?” College admissions or breaking into some cricket team are wrongly seen as ends in themselves. Such short-term aims do not cover up for the absence of a larger purpose.

The purpose need not always be ambitious. It can be as simple as raising a family or teaching a few kids or even cultivating one’s own vegetables in a small garden plot. But preferably, it should positively impact others or the world around us, rather than just bolstering one’s own wealth or status. Truck drivers, farmers, waitresses and janitors can find as much meaning in their work as white-collar workers. As Damon puts it, lofty purposes can be “found in the day-to-day fabric of ordinary existence.”

In the bestselling The Purpose Driven Life, Rick Warren says that those who come close to fulfilling God’s purpose for them on this planet are more likely to be motivated and fulfilled, despite setbacks and hardships. While religious faith or even spiritual ends can serve as a purpose, one of the issues confronting younger generations is that churches and other religious organizations no longer serve as moral tugs. Secular purposes can just as easily fill the vacuum, but they don’t seem to be enticing many in the younger cohorts.

Usually people who pursue ideals like Beauty, Compassion, Justice, or Truth are likely to feel more fulfilled than those who merely garner hedonistic experiences or chase materialistic goals. While Damon is not downplaying the significance of financial security, he questions “the glamorization of money for its own sake.”

Anshu Gupta: Touching Real Lives

After intentionally eschewing a material pathway for himself and his family, Gupta has won a litany of awards and featured in a slew of national and international publications. To name only a few of the honors he has received, an Ashoka Fellowship in 2004, an inclusion in the Forbes list of India’s most powerful rural entrepreneurs in 2010, a Schwab Foundation Award in 2013, the Ramon Magsaysay Award in 2015.

Yet perhaps some of his most memorable encounters are still forged inside villages and on city streets. There was one time, when Gupta, his wife and then 12-year-old daughter Urvi, were distributing blankets at night, between 10 p.m. and 1 a.m., near Nizamuddin in Delhi. After receiving a blanket, one of the recipients started calling out to them, and chasing their Maruti 800 car. The man had one leg missing, and he was running behind them on crutches. When he neared them, he threw his hands up into the air and said, “This is my Eid.”

That instance really touched Gupta and evoked memories of Munshi Premchand’s stories: “These are the small things which are actually not small. This is the soul.”

From The Path to Purpose: The Eternal Quest for Meaning

The turn towards meaning or purpose, is also fueled by accounts like Viktor Frankl’s Man in Search of Meaning. Despite the loss of all his intimate family members, and having to withstand unimaginable horrors inside Nazi concentration camps, Frankl was resolute about surviving. He had fashioned his own life mission: to draw lessons from his experience and to write about it. He later propagated ‘logotherapy’ to help people find a purpose in life and fortify their mental wellbeing.

Lives like those of Viktor Frankl and Anshu Gupta show us that creative and generative pursuits, propelled by deeper callings, are not easy; but maybe, as Damon suggests, such uphill battles against impossible odds, are the path to happiness.

References

Damon, William, The Path to Purpose: How Young People Find Their Calling in Life, Simon & Schuster, 2008.