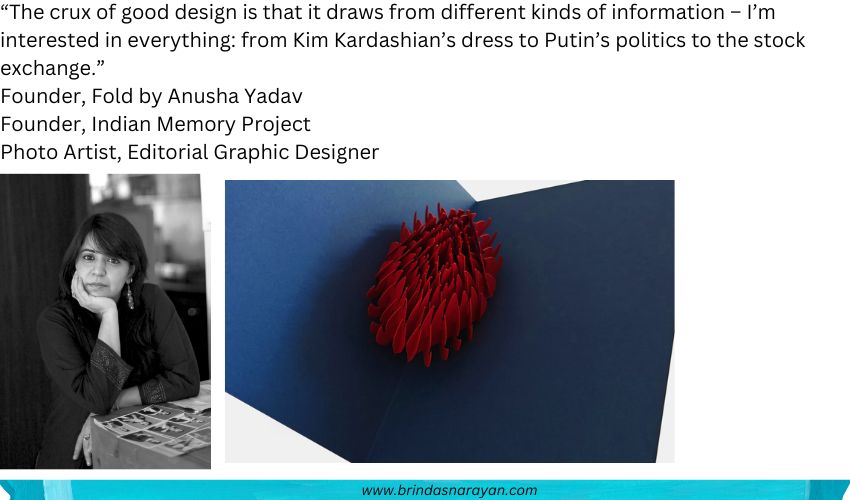

Braiding Time: Journeying with Anusha Yadav Across Cultures and Memories

Yadav’s Father: A Creative Tinkerer

Anusha Yadav was raised in a home that prized culture, creativity and hands-on tinkering. Moving across continents, from the UK – where her father studied for his PhD and taught at King’s College, and her mother worked at a lens factory – to the US, and then to India, she organically imbibed a multicultural sensibility. While she spent a large chunk of her growing-up years in Jaipur – from the age of 7 till she headed to college, she’s retained a connection to the UK as a “stepmother country.”

She cites her father as a significant influence. He embodied what the writer Elizabeth Gilbert would describe as a hummingbird’s approach to work. Unlike jackhammers that stay fixated on a particular passion, hummingbirds move from field to field, leaving an imprint on different domains. From being a professor and a scholar at prestigious universities, he started a factory, then shut it down, engaging in various side gigs before the term was in circulation.

Yadav observed him building stuff from scratch, assembling a computer from its constituent parts, or hewing limestone tiles – a physical task that the whole family engaged in. Along the way, they tided through financial troughs, so a certain tenuousness was woven into her memories. Such uncertainty was heightened by her father’s passing when she was only 12, though his willingness to toy with possibilities became her trait too. There were other intimate role models. Like her uncle and aunt, Rajendra Yadav and Mannu Bhandari, both Hindi literary stars and founders of the Nahi Kahani movement.

Vocal Contests to Design School

Anusha herself was trained in classical dance and music, so much so that she even won trophies at vocal competitions, and performed for All Indian Radio and Doordarshan. At one event, Pandit Jasraj suggested that she should move to Delhi for tutelage. While that didn’t happen, she absorbed her family’s imperative “to be really good at whatever you do.” Growing up in a smaller city, and living through constrained times, she learned resourcefulness – to make the most of whatever one has.

After the 12th Grade, she gave the fiercely competitive entrance exam to National Institute of Design (NID), Ahmedabad a go. Knowing that only 30 students were admitted each year, she had lined up backup plans. But she slid right in and as it turned out, NID was a perfect fit. She soaked up the cultural shocks and liberal ideas, despite other young adult challenges: surging hormones, conflicting emotions and classroom politics. Surrounded by incredibly talented peers and seniors, she watched folks combine skills across domains – music, art, dance, design – in a multidisciplinary manner that resonated with her.

Crafting Ads, Shifting Mediums

On graduating from NID, she gravitated towards advertising, entranced by heated debates over “the placement of commas or the percentage of magenta and cyan.” Joining Enterprise, she was struck by its founder Mohammed Khan’s fervor. She watched him tear up artworks in a pernickety pursuit of perfection, a theatrical obsession with quality that struck a chord. She noted too that the best designs emerged from collaborations between writers and artists, highlighting the value of teamwork.

Working under Gopika Chowfla, whom she describes as one of “finest graphic designers of that time,” she later moved to Chowfla’s exclusive design studio – where she worked on art and writing and other aspects of design, while interacting with clients and overseeing the end-outcome and learning to make good coffee. Later, more senior advertising profiles in Delhi and Mumbai, taught her to market effectively and communicate to diverse audiences, especially in India’s multilingual mélange.

As the landscape continued to evolve, Yadav observed that some of the original freshness, and attention to quality was diluted by formulaic approaches. Sensing a need to strike out on her own design journey, she turned to photography – a field she’d grown passionate about after working as a Design Director with PhotoInk, a studio that features legendary Indian photographers like Raghu Rai and Ketaki Sheth.

Beyond the Lens, Into Stories

With her pivot to photography, Anusha found a new mission: to make high art more accessible to the public. She believes that the art world ought to draw outsiders into a realm that often feels like an exclusive club. Her photography projects include “Impersonations” – in which Yadav captures self-portraits of herself as historic, sassy personas like Mehr-un-Nissa (Jahangir’s main wife) or Mata Hari (a Dutch courtesan, suspected of spying for the Germans) or her own grandmothers.

Or “In Tune for Fame”, where she photographs children readying for a broadcast talent contest. The pictures radiate a behind-the-scenes frisson, of child and parental yearnings for studio-lit glows. To put her subjects at ease and enable candid shots, Yadav even sang a few ditties, imparting a sense that she was “one of them.” Compared with her own childhood competitions, she couldn’t help noting how much more charged the atmosphere was, with children ferried from all over the nation, dressed and styled meticulously, imbued with burning “ambitions to be famous.”

As a photographer, Anusha is sensitive to the subject’s contributions: “A photograph is literally made between two people.”

Archiving Pasts, Curating Histories

The Indian Memory Project emerged organically from a different idea. She had planned to create a coffee table book documenting diverse wedding traditions in India. In response to what she felt was a disconcerting homogenization among weddings: “Weddings have now become like airports, they all look the same.” For this, she asked her Facebook friends to send her wedding pictures. Fortunately for her, instructions weren’t followed to the tee. Folks sent her pictures, but not just of weddings. Of grandparents on a boat in Kashmir, of relatives stranded by Partition, of two women who swiveled between dual selves: pious and submissive by day, but who scooted to a photo studio each evening to pose as the actress Nargis, taboo cigarettes between their lips. These ancient, sepia-toned images evoked poignant, forgotten pasts.

Yadav realized she had stumbled on microhistories that could be stitched into a fascinating archive. As a child, she had been entranced by libraries, by the manner in which they catalogued materials and organized knowledge. As she started gathering pictures and write-ups, labels popped into her head. She kicked off the Indian Memory Project (https://www.indianmemoryproject.com/) with 15 stories, but started receiving a flood of submissions and international press coverage: “It became a wild horse that I needed to tame.”

Forging a “value system” inspired by The National Archives in the UK and the Library of Congress in the US, she resolved that this project would not be commercial – no ads – and would exude an “elevated status.” She edited write-ups to ensure flow and structure: “They needed to begin and end neatly.” Combined with carefully curated images, she intended for the site to garner respect and infuse pride. On talking to reporters from the UK and the US, she realized that “there was nothing else like it in the world.”

Drawing media interest both in India and internationally, the project currently hosts 250 stories, that have also been incorporated into academic curricula across the globe. Yadav continues to add stories, at her own pace: “Sometimes rent-making takes priority,” she says.

Bringing Paper Visions to Fruition

Recalling a visit to the MoMA Design Store in New York in 2001, she says: “I was smitten.” Walking through that space sparked a dream to create her own store, melding great design with her passion for photography and art. After 23 years as an Editorial designer, she was ready to transition to a retail-oriented phase in her journey. This sparked off “Fold by Anusha Yadav” (https://foldbyanushayadav.com/), where paper takes center stage. She observes that “print design is cinema on paper,” where elements like harmony, melody, and typography coalesce into a narrative.

From pop-up marvels to elegant accessories and stunning, limited-edition prints – FOLD incorporates painstaking craft to morph paper. At this point, the FOLD store is online, but she envisions a physical outlet in the future. She also revisits marketing basics, adapting her erstwhile skills to a new landscape: “Creating is one thing, selling is a totally different ballgame.”

Balancing Creation with Discipline

Despite working as a creator, Yadav maintains a structured routine. She starts work around 10 a.m., with a break at 4 p.m. for resistance training at the gym, a workout she avidly endorses for all women above 40 . She hires assistants on a need-basis, rather than signing up full-time employees.

To new designers emerging from a plethora of programs, she strongly urges them to be multidisciplinary. And to stay “consistent” – to exhibit reliability, grit, commitment and attention to quality – instead of trying to be “authentic”, led by real but unreliable emotions. As Anusha observes, we are all malleable selves, inclined to change and grow in new directions. Why not allow for surprise pop-ups rather than sticking to trodden paths?