In the Footsteps of Color: The Story of Badri Narayan

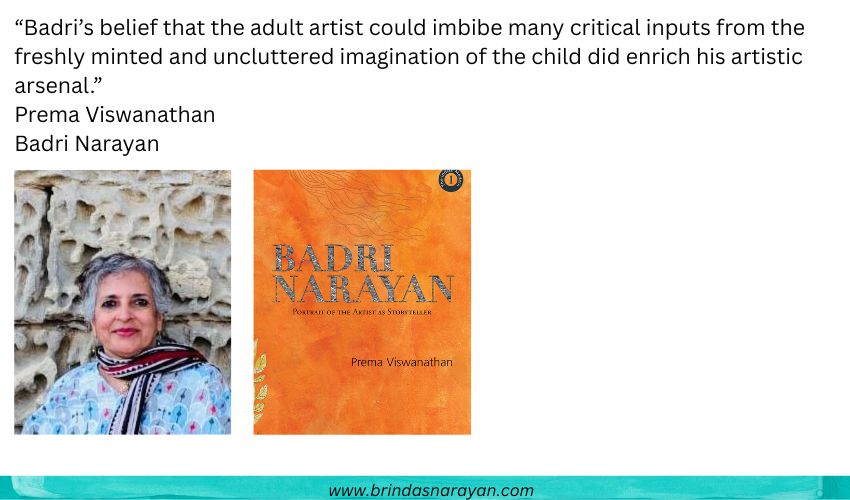

In his book on Creativity, the Hungarian-American psychologist, Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi traces the contrarian traits that make up Big-C creators: folks who reshape their domains, push boundaries and leave lasting dents on culture. The Indian artist Badri Narayan would certainly embody the psychologist’s view that creators straddle paradoxes with a felicity that might elude others. In Badri Narayan: Portrait of the Artist as Storyteller, Prema Viswanathan deftly evokes the soft shades and brittle textures of one of the nation’s extraordinary artists.

Early Stirrings of an Artist

Born in 1929, in pre-Independence India, to a family that was once-wealthy but later slid into penury, Narayan started dabbling with a practice that was widespread across Indian households: the drizzling and dotting of rangolis in his grandmother Nacharamma’s home. Losing his mother to TB at the age of 13, he also had to cope with a mostly absent father. Later in “Drawing for Father”, he seems to have made peace with his parent’s “volatile temperament and irresponsible nature.”

Withdrawing into himself, the child Badri was often found drawing pictures on the floor. Deeply influenced by his grandmother and mother, he absorbed and radiated a “feminine energy” in his androgynous persona and in his works.

Shaped by Diverse Forces

Leaving home at the age of 16 to work as a clerk at an ordinance factory in Secunderabad, he was like Einstein and Ramanujan, indifferent to institutional trappings and formal credentials. Perhaps he could withstand the grunge work since he had his rich imagination to compensate. All along, he sketched, wrote poems and stories. His first story was published by the Illustrated Weekly of India when he was 19.

Despite possessing a mere school certificate, he was an avid learner. As a child, he trudged barefoot from his home in Chikkadpalli to the Asafia State Library to soak up volumes on history, anthropology and mythology. Such wide-eyed curiosity was to linger with him through life. Even as he abjured prevailing or dominant trends, he sponged up impressions from everywhere: from the low-brow and high-brow, from the East and West, from the past and present. His paintings drew from a Mumbai water-melon seller or vegetable vendor as much as they did from the French Henri Matisse or Marc Chagall.

Minimalist Life, Maximalist Works

A minimalist when it came to his life and personal possessions, he was noticeably exuberant in his works. Like a stereotypical artist, he wore a “trademark khadi kurta.” Deeply influenced by Gandhi, he mimicked the leader’s spartan belongings and slick storytelling. Impressed by how Gandhi had with a few elements – his spectacles, walking stick and semi-nudity – rebuked Western materialism and the Empire’s pretensions, Badri bought into his idea of non-violence. When the artist himself faced fractious situations, he tried to adopt “non-retaliation.” Like the Mahatma, he felt at ease with the working classes and with those who made the most of little. When Gandhi was killed, Badri grieved like he had lost a parent and even published a poem in The Illustrated Weekly, expressing his anguish. The leader had filled a void created by his mother’s early death.

Narayan had other resonant inspirations. His vision was steeped with Indian miniatures, Japanese practices, Buddhist folklore, Puranas and scenes from his window in Chembur. While he did not travel much, he stayed a voracious reader. Moving to Bombay in the 1950s, he chose not to join the Progressive Artists Group (PAG). While he did relish long conversations with Gade, Francis Newton Souza and KK Hebbar, he retained a critical distance from PAG. He seemed to prefer the role of an onlooker, watching the ferment from the sidelines. He felt, at that point, that PAG members were overly shaped by the West, a view he retracted later.

His own storytelling modes were rooted in Indian traditions. Some paintings deployed a “monoscenic” approach, wherein a single scene could be a stand-in for the whole story. At other times, he used a “synoptic” mode, where multiple events were collapsed into a single frame, ignoring “causality or temporality.” While he retained his distinct viewpoint and signature style – most famously, the “singing line” featured across many works – he stayed open to suggestions, including from younger generations. For instance, one of his granddaughters asked why he didn’t use brighter hues. In response, he experimented with different colours and was stunned by the results.

The Spirited Curiosity of a Child

Badri retained a childlike wonder and explorative zeal till the end. He believed that all children had an inherent artistry and we often educated them out of a capacity to imagine. He did not endorse modern “pressure cooker” modes of parenting or schooling. He taught art at the Bombay International School (BIS) for 16 years, applying the guru-shishya parampara with its emphasis on the teacher-student dialectic. He was remembered fondly by a student as “the paan-eating, kurta clad friend more than teacher.”

He allowed students’ art to blossom without imposing rules. Attracted by the Arts and Craft movement in England, he deplored the fact that modern children could not absorb the aesthetics of traditional wooden toys, and played instead with plasticky Barbies or with electronic games. One of his BIS students was the filmmaker and writer Riyad Wadia, who unfortunately died in 2003. His documentary on the transsexual Aida Banaji, A Mermaid Called Aida, incorporated symbols from his art class, like that of the mermaid.

A Marriage Marked by Strain

Though Badri’s marriage was more conflict-ridden than he might have wished for, Viswanathan observes that we can’t ignore the sacrifices made by his wife, Indira, to fuel his artistic journey. Though she emerged from a wealthy household and had a BA in Philosophy, she managed the practicalities of their home and the brass tacks of parenting. As is often the case with creative or publicly successful men of that era, their dreamy careers often imposed invisibilized costs.

Healing Rifts with Art

In Badri Narayan: Portrait of the Artist as Storyteller, the author captures the quicksilver flashes of a life amidst the nation’s mercurial history. In the context of the contemporary polycrisis – wars, climate change, economic upheavals – it would serve us well to return to Badri’s unfettered vision. Which, as Viswanthan puts it, is “the portrayal of life as a chiaroscuro of light and shade, of exuberance and equanimity, of tradition and modernity, of shunya and purnam.”

References

Prema Viswanathan, Badri Narayan: Portrait of the Artist as Storyteller, Marg, 2020