Can’t: An Original Take on Contemporary Womanhood

Nena is allergic to water. So she has an annual bath. By first embalming herself in petroleum, then dunking a cold water bucket over her head. To survive this yearly ordeal, she wraps herself in layers of cotton, even as she quickly rids her body of the smallest drops of moisture. Since, as Nena herself acknowledges, human bodies are mostly made up of water, being allergic to water implies that she’s also allergic to herself.

Can’t is a story of a woman who embarks on a strange and bold journey. To visit the sites of her husband’s infidelities, to meet the people he might have had affairs with. “She was going to hunt them down, these ghosts in her marital bed, and haunt them right back, one by one.” Nena, who’s currently in her 70s, is accompanied by a 17-year-old boy, who’s also the novel’s narrator.

Her marriage story starts out like that of many young women: hitched up too young, carrying Mills & Boon or romcom dreams into a marriage that unpeels like the slow shedding of a snake’s skin. The experience being flaky, dry, reptilian. But perhaps Nena should have seen the signs.

If only she hadn’t been so heart-wrenchingly young. Or guileless. After all, even on the first night, of her hastily arranged marriage, the husband oozed with resentment. It was a jealousy that turned him away from his made-up and distinctly more erudite bride, his insecurity morphing into a pathetic refusal to touch her: “As it is, her flawless diction, pedantic literary references and blind faith in the goodness of mankind struck terror in his heart.”

He leaves her the next day, does not return for six months. Does not send word. She decides with a plotting friend to surprise him in the city. To visit his shabby urban pincode. Inevitably he’s not home. In the morning, when he finds her waiting, fallen asleep on a bench, he’s furious. He fumbles with a reason for his night outing. He was away with an old aunt. Someone he needed to care for.

She returns, contrite, apologetic. It’s her fault, after all. Always. She shouldn’t have bothered him like this. She shouldn’t have set out on such a dangerous journey, interrupted his busy work, however imprecise and murky it seemed. On the way home, the friend and she are silent. “The giddy-headed giggles of the onward journey were ripples of shame in their bloodstream.”

Now, when she visits the area inhabited by that mythical “elderly woman,” a shopkeeper tells them what they already know. That the area had been occupied once by “women of ill repute.”

When he eventually does summon her to the city, she wonders if she should have arrived with exit money stitched into a hem. (Like a servant of hers has done, and uses, bizarrely enough, rather too soon.) It’s clear that he sees her as a “trophy wife,” someone who makes him look respectable, despite their occupying “separate bedrooms in separate wings.” Whatever she does, she can’t seduce him. Can’t attract so much as a glance or touch from him.

At a party, she hears of his other interests from another man. Of their being two suitors for one woman, her husband being one. In those days, women who worked, office-going women were “considered fair game.” When she confronts him, he denies everything. Forcefully. Strongly. She intentionally shrinks her sights, stops taking in the evidence.

Later, when she meets the rival lover of “Jaan” – the woman two married men were chasing, she learns that her husband was a rapist. As a predatory boss, he had insisted that the woman spend hours with him in the office, attending to his petty needs. Then he raped her, driving her to suicide. She had been in love, all along, with the other man.

To make matters worse for Nena, when she bumps into the ex-rival, he flashes a ring, gifted by the woman, to confirm her love for him. That dazzling diamond ring had been Nena’s once, gifted to her as a child by her father, later stolen by her husband, who had then given it to his love object – with the woman in turn bequeathing it to her true love. Life is not just a circle, but a twisted, knotty one.

The duo meet one of Nena’s best friends in Japan, who was groped by the said husband, on a car ride, while her own husband sat in the front seat, by the driver. The cheek of the man. Who hadn’t even bothered to woo her friend, to ascertain her acquiescence: “As if sitting next to him had been foreplay enough.”

And then the servant, who vamoosed too soon from her husband’s home. At that point, she hadn’t wondered why the woman had been in such a hurry to leave. Now she knows. When they wind their tortuous way to the woman’s house in a remote village, she’s already dead. The mother says she returned from their home with AIDS, refuses to reveal more. She says there’s no baby, in response to a persistent question from Nena. As if this journey were to recover an orphan that her husband had left behind. For her to claim.

Later, a young girl gets inconveniently pregnant. Her husband’s involved in politics by then, he needs to keep his reputation intact. Nena shepherds her to a risky abortion, despite the doctor’s warning that the pregnancy is advanced. Nena waits outside, while the girl’s escorted into an “airless ultra-bright chamber.” The baby’s snuffed out, but that’s not the end of it. By that evening, the girl bleeds to death. Nena’s husband has a stiff drink to wipe this off his conscience.

By then, many other women land up on the doorstep, with paternity suits. All of whom Nena deftly dismisses, with money and words of advice. Like stay away from sleazy men. What she doesn’t need to add is men like her husband. “In this way, [they] led parallel lives in the greatest of harmonies.”

She also tells the young protagonist that as we age, we remember the past in vivid detail, and start paying less attention to the present. We are now tangled up in regrets – things we shouldn’t have said or done, rather than in actions we are taking now.

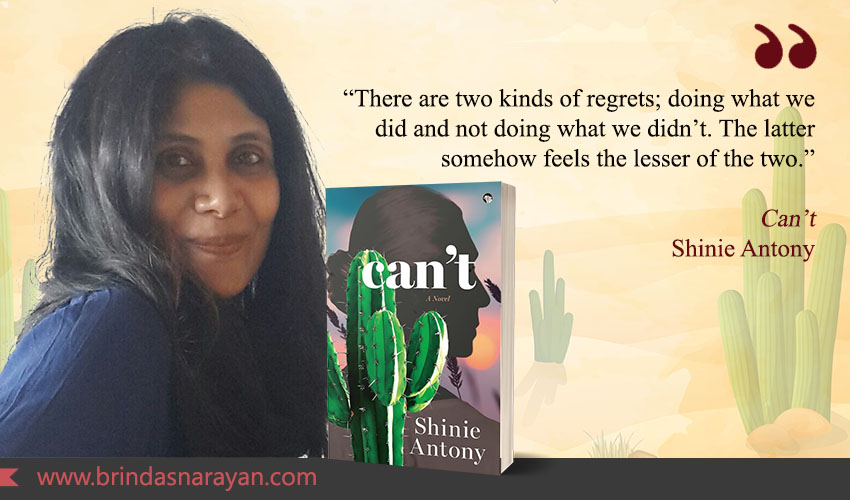

Segueing between past and present, gradually revealing Nena’s layers and secrets, Can’t is a deep, lyrically-penned portrait of contemporary womanhood. There’s something Nena can’t do. And something shocking that she does, as a result. In a country where the wedding industry is ballooning to a preposterous size, this haunting portrait of a marriage and a woman’s journey towards self-discovery and redemption will linger like a bittersweet, juicy paan.

References

Shinie Antony, Can’t: A Novel, Speaking Tiger, 2024