Savoring Time: A Taste of Delhi from Royal Kitchens to Street Vendors

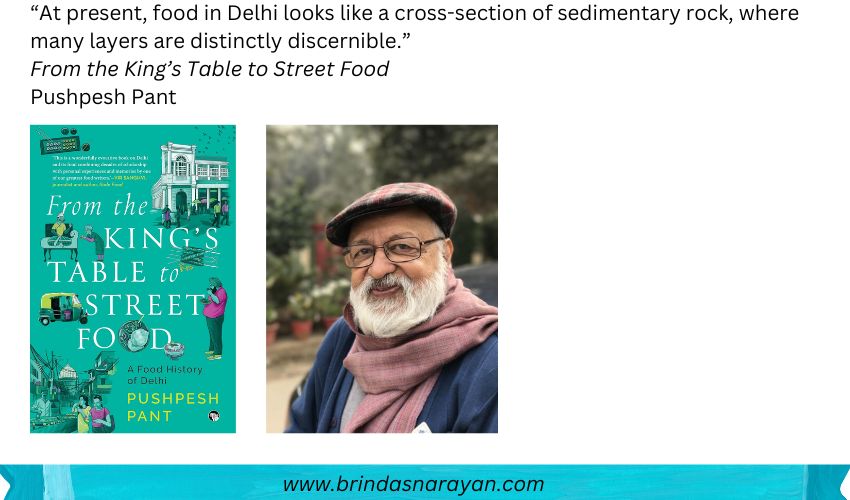

From The King’s Table to Street Food, as Pushpesh Pant acknowledges in his Preface, is not just a history of Delhi embedded with recipes and foodies stories. Nor is it a food book, layered with nuggets of history. Rather, it’s a memoir of his time in the nation’s capital, where he started out as a student, watching the place morph over decades into the kaleidoscopic jumble that it is today.

Epicurean Echoes of Indraprastha

The work was triggered by an unusual ask: when he was asked to curate a menu based on foods eaten in the Mahabharata, when Delhi was Indraprastha. This was part of a program that was cheerily branded “the kitchens of undivided India.” As an academic who taught International Relations for forty years at JNU, the project appealed to his scholarly and gourmet instincts.

After all the epic is embedded with foodie tidbits. Take Bhima, who assumes the disguise of a cook, during the year of the Pandavas’ camouflage. While the fierce mace-wielder is personally fond of ladoos, there’s no doubt he could whip up other dishes. Well before fitness mantras were in vogue, the Bhagvad Gita slots eaters into three types: Satvik, Rajasik and Tamsik. Indicating that we are what we eat. The heartwarming tale of Krishna and Sudama, where the latter brings the poor man’s “rice-choora” to Krishna, suggests that the “riches of poverty” were dearer to him than lavish treats whipped up by the well-heeled.

All this research on foods eaten by the Pandavas, not just in the palace, but also while foraging in forests, whetted Pant’s appetite to knead history, food and memory.

Nostalgic Flavors from Pant’s Past

The adage goes that music often invokes the past. Maybe foods do that too: draw out memories, of places and times that can feel wistful. As a young boy at home, Pant exulted in flavors from Delhi being ferried by visitors who brought Sohan halwa and multihued Sindhi halwa. These sweets were bottled up and rationed over many days, recalling how nothing was ever as plentiful as it might be for many today.

On trips to the capital, his family would saunter through Hanuman Mandir, a space jostling with color, noise and enticing objects: “cheap toys, tinsel, bow and arrow sets, cardboard swords covered with foil, kaleidoscopes, and ‘dark glasses’ made with thick paper and tinted film.” It feels incredible to re-enter that pre-technology era, when paper and cardboard items were thrilling and magical. From there, Pant’s father would cart them to Wenger’s, where they would be treated to patties and pastries. Naturally, forbidden foods were more enticing: chaats and tikkis from street vendors, that their father shunned for being germ-ridden.

When Pant later moved to Delhi in 1965, he stayed at a mess. At that point, the country was riddled with food shortages. Everything was strictly apportioned. Pant had to flash his ration card at the canteen to add himself to the register. Most dishes, reminiscent of potato famines in other parts of the world, were made of the ubiquitous aloo, with only a few dishes being cooked each day. Pictures of folks starving in places like Bihar seeped into the collective consciousness. Yet there were sporadic joys: of dipping into food scenes, like into a dhaba where chewy tandoori rotis were doled out with dhal for a mere 70 paise.

Legacy of Triveni Tea Terrace

Eateries like the Triveni Tea Terrace was frequented by many. Run by Puran Devi Acharya, the Terrace was always impeccably run. With a spare menu consisting of a few simple dishes, the establishment exuded hygiene and consistency. Their keema, matar, phulkas with shami kabab and cheese toast were dished out by smartly outfitted waiters and cooks, bustling with customer-friendly smiles well before the notion of “customer service” had entered the business lexicon. Perhaps, it was the old-fashioned ‘Athithi Devo Bhava’ that operated there.

Makhan Singh, a waiter there, later worked at the home of the journalist Vinod Dua. In the manner of Kolkata’s well-known addas, the place attracted actors and theatre personalities including M. K. Raina, Balraj Pandit and others. One could also watch Manipuri dancers at a small amphitheatre that used to overlook the eatery. Walkways in and out of the building served as galleries, featuring artists like Gieve Patel, Bhupen Khakhar and Rameshwar Broota.

Brews and Banter

Iconic messes like Nair’s Mess, operated out of a servant’s quarters, carting flavors from the South to Malayali and Tamil clients. The Nair’s spicy rasams beat soups at high-end joints. The India Coffee House hosted stalwarts like the barefooted MF Husain or the freedom fighter, Dr. Ram Manohar Lohia. The Coffee House, known fondly by its clients as PRRM (“Price Rise Resistance Movement Coffee House”), not only brewed low-cost coffees, but also sparked frothy arguments. At the Sapru House canteen, over samosas and steamy tea cups, one could spot Gulzar, in his trademark white kurta, or even the PM, Jawaharlal Nehru. In such spaces, waiters knew what particular clients needed, ferrying those dishes without waiting for orders.

Beyond Biryani: Delhi’s Diverse Bites

Knowledge of Delhi’s food history tends to be dominated by Mughlai cuisine, by the rich, dry-fruit laden, aromatic stuff devoured by royals inside Mughal palaces. This book hopes to correct that. Since, as Pant observes, there are so many other influences in the city’s past, including Turko-Afghan, Awadhi and Punjabi culinary styles.

In the modern history of Delhi, the ruler Alauddin Kilji has been villified in historical records, especially for his raiding of the Chittoor fort, where he was apparently besotted with Queen Padmavati who then committed sati to avoid being kidnapped. Kilji’s other traits are less well known. He was very conscious about controlling the prices of essential commodities and foods like wheat, rice, and even lentils. He ensured too that barley, which was mainly used by lower income folks, was always cheaply available.

Mohammed bin Tughlaq, infamous for impetuously shifting his capital from Delhi to Daulatabad and then equally impulsively re-shifting it from Daulatabad back to Delhi, hosted lavish feasts inside his palaces. Round breads, probably similar to naans today, were accompanied by rich meats cooked with onions and ginger, sambusak, pulaos and halwas, all of which appears in jottings by Ibn Battuta, who visited Delhi then.

Such bustling in the kitchens persisted during Akbar’s reign. Akbar himself didn’t care much about fancy foods and ate simple meals. But his advisor, Abul Fazal, loved food. One of the designated “nine gems” in Akbar’s court, Fazl wrote books like Aini Akbari and Akbar Nama.

Akbar’s kitchen had about 400 cooks from places like Persia and different parts of India, forging together cooking styles, such as Turkish, Afghan, Indian, and Persian. Ingredients ranged from ducks and waterfowl to the best vegetables and fruits. Typical meals included poori, dal kachori, and various kinds of baked breads, sherbets and kormas. Soups were called Aash. Mughal nobles, in turn, competed to impress guests with variegated feasts.

Old Flavors, New Plates

Contemporary Delhi might be a far cry from those times. But even chains like KFC and McDonald’s have been compelled to change their offerings to cater to local appetites. And some of those older ways of cooking and feasting have come back, as new-age chefs plunder ancient recipes to evoke not just childhood memories or a forgotten city, but also different ways of tasting the world.

Pant is a delightful storyteller. He recounts the origin tales of spaces like Moti Mahal (founded by three friends who survived the Partition, and accidently met at a liquor joint), the story of the ubiquitous Momo (the steamed street food that appeals equally to health-obsessed elites as it does to budget-conscious denizens). And takes on the mammoth and daunting task of charting the sheer explosion of food scenes that makes it difficult to pinpoint what ‘real Delhi’ food is or ever was.

References

Pushpesh Pant, From the King’s Table to Street Food: A Food History of Delhi, Speaking Tiger, 2024