Contemporary Britain Through the Lens of Twelve Black Women

Remember Shankar Mahadevan’s Breathless? The Booker-winning Girl, Woman, Other has that quality of indefatigability to it. It’s like the author has all these tales packed into her, and she narrates them in a gush, so speedily, so fast, she can’t brake her telling with spoilt-sport periods. Since Evaristo, as she admits in interviews, is more deft with poetry than she is with prose, she does what many creatives are asked to do: leans into her strengths. And forges the whole novel in a singular sing-song, that’s part poetry, part prose. This is not stream-of-consciousness writing, because it’s carefully crafted. Her run-on sentences squiggle and zigzag across pages that ooze a calibrated lightness.

For a book that weaves together the stories of 12 black women, whose lives overlap and intersect, with some tied more closely and others only loosely connected, Evaristo’s distinct patter works. This book, after all, is addressed to a particular type of reader: “For the sisters & the sistas & the sistahs & the sistren & the women & the womxn & the wimmin & the womyn & our brethren & our bredrin & our brothers & our bruvs & our men & our mandem & the LGBTQI+ members of the human family.” Which should theoretically encompass all readers, except one can envision some turning away with “not for me” sighs.

Honestly, you shouldn’t. Because even if you forget Evaristo’s characters or the minutiae of their lives, the reading of this book will linger like a tart aftertaste. It’s a window into modern-day Britain like no other – embodying how terms like “multicultural” or “diverse” are too bland, too stale to describe the teeming variety of experiences in the island nation. Just to give you a flavor:

There’s Amma Bonsu, a radical, socialist, feminist who’s currently in her fifties. Who at one time, with her black theater partner Dominique, dwelt in the fringes, poised to hurl “grenades at the establishment that excluded her.” Now she’s, self-consciously, a part of that establishment. Her play, The Last Amazon of Dahomey plays at the National, when the theatre gets its “first female artistic director.”

Life on the margins was never easy, or pleasant. After living in sordid squats, then in a “former office block” with vegetarians, Hari Krishnas, punks, anarchists and radical feminists who predictably fell apart, after couch-surfing with friends, Amma savors her midlife stability: The homeownership, the 19-year-old daughter, Yazz, who was fathered by a gay professor, Roland. The utter commonness of her middle-aged worries. Like when will Yazz be back from her night out? And why can’t that girl wear a helmet when she’s out biking? Doesn’t she know the difference between:

“a/ getting a headache

b/ learning to talk again.”

Or Yazz, the rebellious daughter, who’s very clear about her ambition. She plans to be a columnist in a “globally-read newspaper because she has a lot to say and it’s about time the whole world heard her.” She’s also, like many daughters, amusingly snarky and laser-eyed about her mother’s success. She observes how Amma was once a struggling artist like her other theatre mates. But having now made it, she’s “very snooty” about the rest.

“….as if she alone has discovered the secret to be being successful

as if she hasn’t spent way too many years of her life watching crap television while waiting for the phone to ring”

As Evaristo knows, parents can hoodwink anyone else, but rarely their own sharp-tongued, always-watchful kids. Yazz notices the gentrification of London, the posh gastro-pubs & champagne lounges taking over working-class bars, where people used to bemoan Maggie Thatcher and the miners’ strike over sloppy beer spills. Equally, she notices her mother’s easy acquiescence to the new settings. Her ease with the “artsy hotspots” where once she might have turned up her hippie nose.

Yazz is equally dismissive of her parsimonious gay father, who has money for Cartier-Bresson photographs and ultra-fashionable suits. But not enough to pay her college fees. She steals high-denomination notes from jackets racked up in his walk-in closet. And pries into his secrets:

“…you never know people until you’ve been through their drawers

and computer history”

Then there’s Carole, the banker. Her blackness erased as much as it can possibly be, “her straightened hair scraped back into a martial topknot,” “her eyebrows plucked with calligraphic flair.” She lives in a world far removed from that of her college friends, or her own striving mother’s one-time struggles. Who was an educated immigrant from Nigeria, but was forced like many educated immigrants into domestic labor. Carole’s eager to leave that behind, as she rides glass elevators into an “orbit of equities, futures and financial modelling.” She stacks her shelves with self-help books that dish out can-do American messages. Like “if you project a powerful person, you will attract respect.”

This is a book that breaks rules. It’s populated with characters who straddle times and generations. But it’s also plotless. And filled with oodles of back story (another writer’s no-no). Yet it works. It’s a Booker win that feels richly deserved.

References

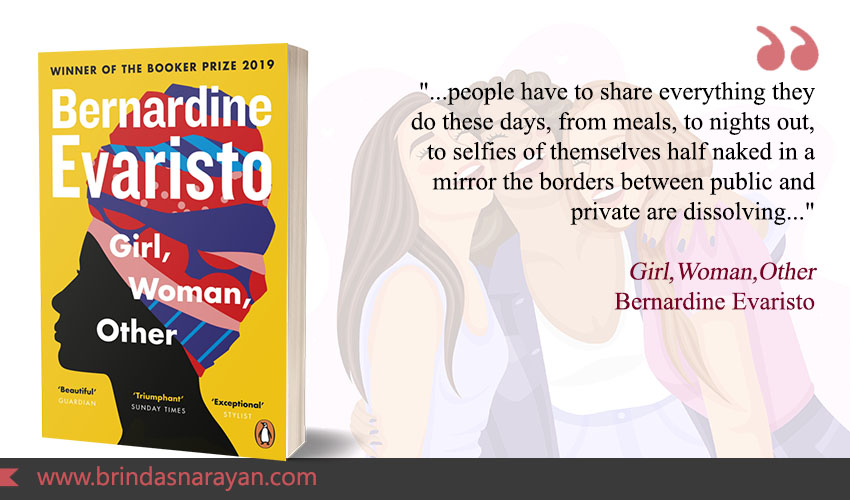

Bernardine Evaristo, Girl, Woman, Other, Penguin Random House UK, 2019