Ganga Unbound: A Feminist Take on an Ancient Epic

In her previous work, Kaikeyi, Vaishnavi Patel had dwelt on the point of view of a much maligned character in the Ramayana. Unsurprisingly, or perhaps not coincidentally, that character was a woman. A mother who had her virtuous stepson, Ram, banished to the forest in order to seize the throne for her own offspring. That at least is the most common or familiar version, but it’s one that Patel subverts in her feminist retelling of the well-known epic.

River, Warrior, Woman

In Goddess of the River, Patel narrates an origin story of The Maharabharata, choosing to spotlight Ganga – the bubbling, effervescent, untamable river. Ganga’s brief descent into mortality gives rise to one of The Mahabharata’s more formidable and layered characters, Bhishma. As a self-sacrificing warrior who chooses to remain celibate, Bhishma leads the Kauravas into a battle that he holds misgivings about. In the process of exhuming these epics and reimagining them, Patel centers women who have, to date, held marginal roles, unlike Sita or Draupadi, whose stories have been frequently retold.

Unleashing Ganga

Right from the start, Patel embeds the narrative with an ecological consciousness. When Ganga tumbles down to earth in a free-spirited frenzy because humans pray for her, she says: “I did not know that when humans pray for nature, they pray for something to control.” On the way, she’s caught by Shiva, who seems to tame and control her. He argues, that if he hadn’t done so, she might have destroyed the world. Bristling like most women would inside patriarchal cages, Ganga wonders if such destruction would have been worse than the ongoing violence inflicted by humans.

Fierce Currents, Fierce Love

She’s entranced by the earth when she arrives, its landscapes, its greenery, its rocks and soil, its rough terrains. Displaying her own riverine agency, she doesn’t just go-with-the-flow. Rather, charting her own path and those of her snaking tributaries, she uproots communities who move to her banks. With her are the eight Vasus, semi-divine creatures, human like but not human. They frolic by her side, filled with light and stars and magic.

When an enraged sage curses the eight Vasus into assuming human births, Ganga pleads for their reprieve. Instead, she too is cursed into mortality, morphing into a brooding, mysterious woman destined to mother the eight Godlings. Depicting how motherhood can be both terrifying and profoundly rewarding, Ganga’s own journey is filled with horrific sacrifices. After all, without her king husband’s knowledge, she drowns the first seven infants soon after birth. Returning them gently to her own waters, so they could re-inhabit their freer spirit selves. This almost feels like a mother’s urge to re-induct an infant into her womb, to protect and perhaps control its fate.

Defiant Waters Speak

Given that women are often depicted as passive breeders, rather than as agentic creators and destroyers, Ganga’s story reminds us that power stems from choice. Stopped by her husband from killing her last child, Ganga thereafter watches and also shapes the rise of duty-bound Bhishma, the eighth son who returns to her banks to quench his filial thirsts. As a mortal, she revels in dalliances with Krishna, the boy-god who imbues her with hope and peace, but who will later fight her son, embodying how battles are rarely fought between the righteous and the wrong, or even between this side and that.

This is not a cold, dispassionate account of a river’s birth, life and death. Of its powers to flood cities or to suddenly recede. Ganga is emotive, spilling over with feelings, though she cannily masks her intentions from her husband, Shantanu. In a role-reversal that undermines Shantanu’s kingly authority and his possessiveness over his pregnant wife, he’s not permitted to ask her questions. Patel clearly hopes that the reader does not adopt his restless and glum silence. But is provoked by this book to do exactly that: interrogate ancient tales, since the ramifications on thought and culture filter into the present age.

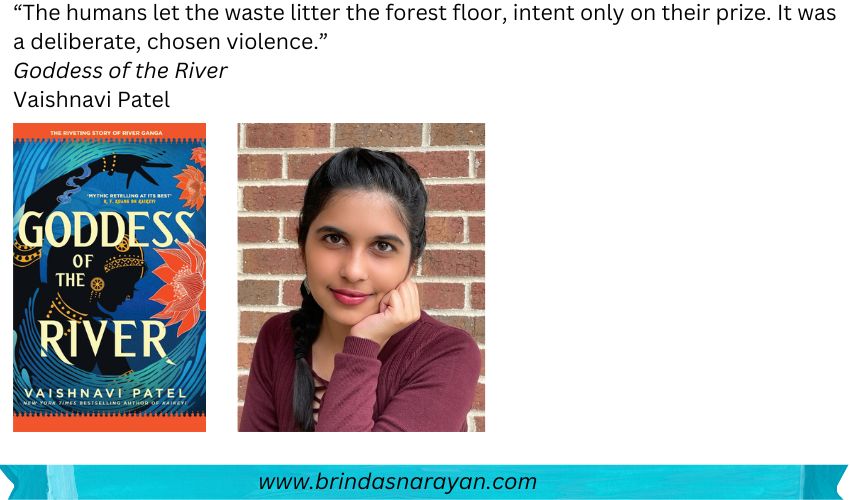

About the Author

Besides being a writer, Vaishnavi Patel is also a lawyer. She focuses on constitutional law and civil rights. She has a new book releasing in June 2025 titled Ten Incarnations of Rebellion.

References

Vaishnavi Patel, Goddess of the River, Hachette India, 2024