Greening Homes and Workplaces: YourGreenCanvas Brings Walden Into Cities

Henry David Thoreau: The Possession of an Unusual Sensibility

At an early age, Henry David Thoreau realised he was going to be different from other members of his family. There was inside him a sense of the simultaneity of time, of the past and future melding into the present. Born in 1817, at Concord, Massachusetts, as the third of four kids, Henry was a quiet and thoughtful child, often lost in his own reveries. His spirited and firebrand mother, Cynthia, noticed that Henry often lay awake after being put to bed. Once when she asked why he didn’t try to fall asleep, he said he had been “looking through the stars to see if I couldn’t see God behind them.”

He may not have known it then, but he possessed a writer’s “double vision,” a capacity to inhabit his own world while also inhabiting the realities of others. He could imagine, as few others could, the plight of the displaced Native Americans, the depredations against nature as forests were cultivated into fields, the irony of a free nation that still upheld slavery. He was trained, at an early age, to recognise bird sounds. But already the mystical warbles of the outdoors were being broken by the raucous sounds of an industrial park. He knew, even as his country was being remade, that such renewal foretold a new kind of extinction.

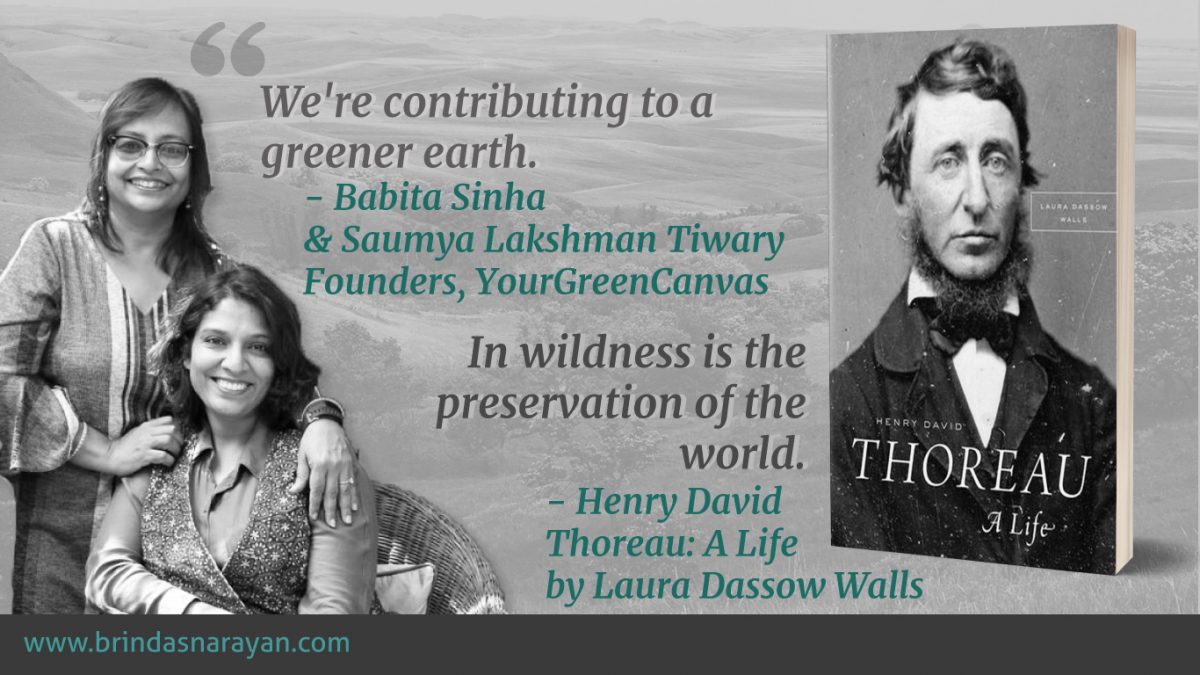

YourGreenCanvas: The Partners Discover a Shared Interest

Since embarking on their greening enterprise (http://yourgreencanvas.com/), Saumya Lakshman Tiwary and Babita Sinha dwell on the stirrings of a similar sensitivity to every tree felled to make way for the rising pylons of progress. Like the time-bending Thoreau, both partners carry memories of greener pasts to infuse their current vocation with greater significance. Saumya’s grandfather was the Chief Conservator of Bihar, with a mandate to preserve the state’s forests from the onslaughts of modernity. Her mother was a Botany professor, who enjoyed communing with plants. Babita’s father was the Director of the Central Potato Research Station, known popularly as the ‘Potato Doctor’. Her mother was a school teacher, with a profound interest in gardening.

Perhaps, as a reflection of the material anxieties that propel most middle-class Indian families towards reliable ladders of success, both women did not consider pursuing Horticulture or Botany or any other ecological field. Instead, they were nudged into corporate careers, with Saumya foraying into Human Resources and Babita into Technical Writing. Though they might not have been conscious of where their real interests lay, they weren’t sufficiently compelled by their mainstream stints to return after maternity breaks.

Having befriended each other as neighbours at an apartment in Koramangala, they embarked on joint family holidays abroad. On such trips, they found themselves entranced by images that others might disregard: the curly twigs of a bush in Norway or the driftwood on a beach. A terrarium workshop in London confirmed what their ikigai might be: an enterprise that offers “greening” solutions –products like terrariums, container gardens, lights with plants, as well as garden development and maintenance services.

Henry David Thoreau:The Memorialised Retreat Into the Woods by Walden Pond

Unfortunately, for Thoreau, it was a tragedy that inspired his ikigai. In 1842, Henry’s older brother, John Thoreau, died of a tetanus infection at the age of 26. Soon after John’s death, Thoreau sunk into a depressive state, staying in bed for a month. This was a period when everything around him, the world, even nature, seemed to heighten the alienation of his spirit from his body. To make himself whole again, he felt mere walks in nature were insufficient. He needed something more powerful, more radical. He needed to stop and listen, to ripples in the breeze and waters, to fluttering leaves, to messages from his dead brother.

Once he had decided to semi-retreat into the woods, to live by himself, inside Nature, Thoreau set about building his own cabin besides the shimmering Walden Pond. “The result was a light and airy house,” surrounded on all sides by trees. He also planned to grow his own food and cater to his other simple needs. Mainly, he was shutting himself in order to write. And he certainly became more prolific than he had ever been outside Walden, finishing two books, the first about his trip on the rivers with his brother, John, and the second, the iconic Walden. For once, everything about him felt integrated, his life and his work, combining into an elegiac composition.

YourGreenCanvas: Blurring the Divides Between the Outdoors and Indoors

Like Thoreau’s historic cabin, the YourGreenCanvas studio conveys the aura of a ‘transterior’ (a word coined by the designers James Durie and Nadine Bush) – a space that obliterates boundaries between the outdoors and indoors. Inside their sunlit, glass-walled living/working space, spidery leaves, emerald mosses and olive-green climbers dispel the concrete monotony of the I.T. city. Sinha and Tiwary have even designed a small plant ‘mural’, with real plants thrusting their living spirits from a moss-embedded wooden frame.

Sensitive to the urban constraints of space and time, YourGreenCanvas fashions “greens” that accommodate different needs. Their terrariums – glass enclosures that hold jade-green succulents, ferns and even twisting Ivy – require only the slightest maintenance. They emphasise how plants can be fitted into the smallest of spaces – tiny terraces or balconies, on a kitchen shelf or living room wall – or across sprawling grounds. They usher greens not only into homes, but also into workplaces, creating plantscapes for offices and co-working spaces. Besides playing a critical psychological role by their sheer presence, plants also filter air and absorb pollutants.

YourGreenCanvas also conducts workshops that teach people to make their own terrariums. They encourage dabbling with plants, even for novices. “Don’t worry if a plant dies,” says Saumya. That was one of their first, harsh lessons in the new business. That some plants, despite careful nurturing and optimal conditions, will die. Perhaps plants teach us, in the most compassionate way possible, that life is always intertwined with death. On the other hand, Tiwary and Sinha emphasise the thrill of watching your first plant sprout to life, and then reach magically towards light.

Henry David Thoreau: Communing With the Wild

Like the founders of YourGreenCanvas, one of Thoreau’s deepest and most profound observations while living at Walden, was to discover and experience for himself, a kinship with the “wild”: “I was so distinctly made aware of the presence of my kindred, even in scenes which we are accustomed to call wild.” Legends started growing around him, of the manner in which he summoned squirrels and birds to his side, with mere whistles. He started communing too with plants, not merely from an aesthete’s viewpoint, but also as someone who needed to feed himself. He realised, even in Nature, there was no avoiding conflicts, dislocations, violence. The very human traits he was trying to self-examine and perhaps dislodge, were also abundant in the animal and plant worlds.

YourGreenCanvas: Perceiving the Glimmers of a Brighter Future

For those of us dismayed by vanishing greens, the partners point to countering forces. They note that many millennials and young kids are interested in plants and gardening. Tiwary and Sinha are, in turn, motivated by other global green gurus – many of whom share their expertise on social media. One of their inspirations is Patrick Blanc, who has built improbable vertical gardens, breathing life into dead walls. Another is Monty Don, a British horticulturist who also hosts a gardening show on Netflix. Even as the demands of a burgeoning city encroach into the greens of our erstwhile Garden City, enterprises like YourGreenCanvas gently and creatively usher them back.

After all, as Thoreau realised in an experiential fashion, humans are inseparable from Nature. As Walls writes, “the mystery that surrounds us, that touches us, that even caresses us, is us, all of us…”

References