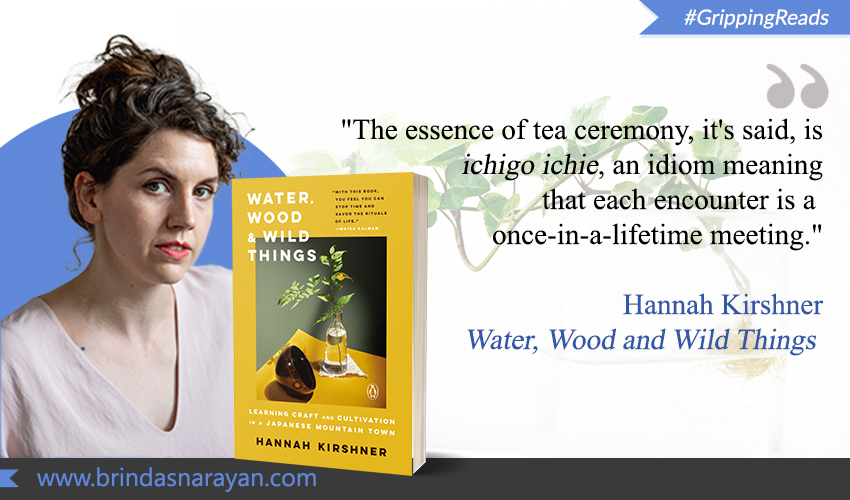

A Brooklyn-based Artist Dives Into Japanese Crafts

About Hannah Kirshner

As someone who grew up on a farm outside Seattle, and then studied painting at the Rhode Island School of Design, Hannah Kirshner might not have predicted the manner in which her life was to be braided into another culture and country. Not even when she first visited Japan at the age of 22.

The journey that led to her first book, Water, Wood and Wild Things has such a spontaneous, go-with-the-flow aspect to it, that can be best described as a happy busyness or busy happiness. And the actions that spurred her travel and her occupations while in Japan seem characterized by a peculiarly Japanese quality. In writing this book, Kirshner seems to have found an ikigai – a pleasurable occupation that also fulfills one’s material needs.

Visiting Japan As A Biker

She first visited Japan to participate in a bike messenger race. For those who are unaware about the makeup of bike messenger races, these are contests held at various world cities to champion the speediest courier cyclists – in other words, the delivery persons and messengers who use cycles to navigate cities and deliver parcels and letters. In these contests, participants are given pick-ups and drop-offs, like they are in their everyday jobs. During that first Japan foray, Hannah felt immediately welcome inside the biking community. She even stayed with fellow-bikers at a “share house.”

A Sake Evangelists Visits New York

Most foreigners hardly talk of such acceptance inside a culture that is explicitly xenophobic. But Hannah returned with unusually warm memories of her trip. Later, one of her Japanese biker friends asked if he could send a friend to stay with her in Brooklyn, New York. Eager to repay the hospitality that she had received earlier, she acceded at once. And so the “sake evangelist”, Yusuke Shimoki landed at her doorstep. As it happened, Kirshner was throwing a party for friends, and Shimoki, who had carted a variety of sakes (Japanese rice wines) in his suitcase, handed out his nuanced picks in special ceramic ware.

Hannah herself was working as a bartender in America, but she was relatively ignorant about sake. Shimoki, on the other hand, was an expert. He even owned a sakegura or a sake bar in Yamanaka, Japan and he invited Kirshner to work with him there, as an apprentice.

Returning to Japan to Apprentice at a Sake Bar

In a short while, Hannah found herself in Yamanaka, which literally means “in the mountain” in Japanese. In those misty heights, suffused with the smell of cypress and sake, Hannah started her apprenticeship – with an intent to glean a deeper understanding of Japanese food and drinks. Located in the Ishikawa region, Yamanaka is a town with only about 8000 inhabitants.

Relatively slow to “develop” in comparison to other parts of Japan, Ishikawa also harbors ancient traditions and practices. In this place, artisans make famed ceramic ware and farmers cultivate rice. Yamanaka is also known for its woodturning crafts, an activity that draws students from Japan and outside. All this makes it a magnet for travel writers, high-end chefs and tourists. Besides, its hot springs have drawn visitors to the area for 1,300 years.

Meeting People at The Sake Bar

Starting out at Engawa, the name of the Sake Bar, which means “porch” in Japanese, Hannah ended up spending the next four years dividing her time between Brooklyn, New York and Yamanaka in Japan. Naturally, as a foreigner, she evoked much interest and curiosity among the bar’s customers. Who included a wide range of people, like the petite 81-year-old Mrs. Kobayashi, who quaffed a “sake, whisky and a beer.”

Hannah’s sheer ongoing presence in a remote town had them mesmerized. “Sometimes they don’t even want to talk to me. Looking is enough to tell their friends about. It gets worse when the regional paper comes to interview me. Foreign woman works at sake bar, they report.”

Besides, she was also struck by Shimoki’s devotion to his sakegura. The bar owner “doesn’t seem bothered that he has time for nothing else: his work isn’t separate from his life – it is his life.” Sake is heated to different degrees, with each temperature affecting the flavor. At first, all types of sake tasted similar to her. “But only a week into my stay, I could distinguish all sorts of subtleties and aromas of persimmon…kelp…pear…pine.”

While at first, she soaked herself in the “poetry of fragrance and flavor of sake”, she soon moved on to other activities. After all, as she puts it, Engawa was also a “place for chance encounters.” At the bar, she met a wood turner, a paper artist and a man who made charcoal in a hand-built kiln.

Broadening Her Learning

Eager to learn a host of other activities and crafts – including the tea ceremony, wood turning, mountain foraging, making traditional charcoal, cultivating paddy and hunting wild boar – Hannah infiltrated a few all-male spaces that were out of bounds to Japanese women.

Aware that she herself was privileged as a foreigner and possibly as a white-skinned woman, Kirshner even dwelt on her guilt. Was it right for her to gain entry when the local women were denied such opportunities? On the other hand, she realized that she wasn’t there to speak for them. She accepted her role as a witness and writer, to merely soak in the landscape with its raw beauty, and ancient (if problematic) traditions. And to record what she imbibed and observed, so she could transmit her experiences to others. As she writes, she was there “to learn about what they do and not to change them. Fair or not, the rules are different for men and women.”

While performing various crafts, she realized how meditative such activities could be. She observed that “[if] you pay attention, tools and materials tell you how they want to be used, but often we get preoccupied with words, thinking too much about what we’ve been told instead of what is right in front of our eyes.” She was also the kind of person to immerse herself intensely in anything she did. “My nature is to dive deep into something for a time – roller derby, bicycle racing, pastry baking, cocktail bartending – until I feel as though I understand it enough.”

Of course the traditions themselves were not static. As Nakajima-san, one of her woodturner friends said: “Tradition is dynamic. It’s not something in the past, but something we are always creating. I want to make forms that will have significance one hundred years from now.”

And it’s cross-cultural exchanges like these, wherein one culture imparts some of its methods to another, that are equally significant in recognizing something that a polarized world forgets: our shared humanity. Written with a poet’s attentiveness and a haiku-like spareness, Water, Wood and Wild Things reminds us that we ought to raise our sake glasses to just that!

References

Hannah Kirshner, Water, Wood and Wild Things: Learning Craft and Cultivation in a Japanese Mountain Town, Viking, 2021