Kyunki Saas Bhi Kabhi Bahu Thi: A Contemporary Look At Indian Mothers-in-Law

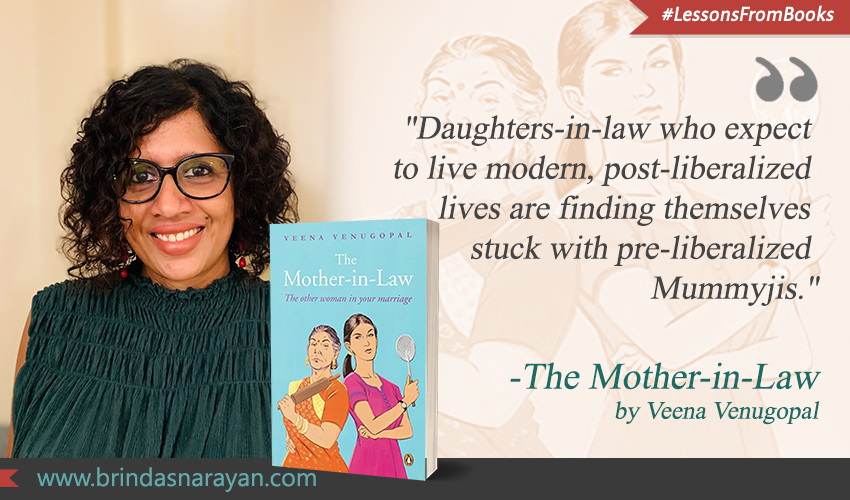

I always knew my own mother-in-law was uncommon. Uncommonly progressive, tolerant and kind; a gentle, mindful presence who stayed remarkably non-judgmental during the humdrum bickering that most couples engage in. So reading The Mother-In-Law by Veena Venugopal, an absorbing account of contemporary saas-bahu dynamics in India, was both alarming and dampening. When embarking on her research, at first, Venugopal set out to write a funny book. One filled with comical clashes between mothers-in-law and daughters-in-law. With the material she gathered, she felt she could not adopt such a light-hearted approach. The stories reported by the daughters-in-law were shocking, heart-wrenching, infuriating.

Despite the social liberalization that was expected to follow economic liberalization, Venugopal reports that the saas-bahu relationship might have regressed, turning the hands of the cultural clock to an earlier era. Most Indian women are more educated than in previous generations. Many work in technology companies or are professionally trained as doctors, lawyers, architects. “Mummy-ji however is stuck at Mughal-e-Azam.” Ironically, many of these mothers might have raised their own daughters to be independent and liberal, albeit with a warning that such freedom might be snatched away by marriage. But Mummy-jis (the typical North Indian term for a mother-in-law) do not expect daughters-in-law to have been raised in a similar manner.

One of the positive changes is that parents of daughters are, in general, more supportive than in earlier generations. They often encourage their daughters to assert their values and stake out their spaces. As a result, however, the parents also become a target of the Mummy-jis’ ire. Venugopal says that a common first abuse that is hurled at daughters-in-law usually takes the form of: “What kind of an upbringing have you had?”

Like in any unequal power relationship, the saas-bahu kinship swivels around control. Even as patriarchy is being worn down in public spaces – active empowerment of women in workplaces, the #MeToo movement, diversity in Senior Leadership and on Corporate Boards – it continues to rear its head in private spaces, and unsurprisingly through women. The mother-in-law wants to control many aspects of the daughter-in-law. In traditional families, this includes choosing the daughter-in-law to begin with, without awarding adequate agency to the man and woman in question. Such control can then seep into other aspects of the daughter-in-law’s persona: her appearance, and especially the clothes she wears: “There is no fashion police stricter than the Indian mother-in-law.”

While salwar kameezes and sarees are generally kosher, many daughters-in-law are forbidden from wearing jeans, capris, skirts and so on. Modern women are then forced to resort to subterfuge. Exiting the home in the approved salwar-kameez and quickly changing clothes in the car, on the way to the party and then back again, before re-entering the home. As Venugopal wryly notes: “Many urban Indian women are adept dressers in the car.”

There can also be another type of mother-in-law, someone who wishes to flaunt a “hip” supermodel bahu, but who also exercises control in other ways. In this case, she gifts her daughter-in-law gym memberships and urges skin bleaches or other “beautification” procedures so that the bahu fits into a type that she can show off.

Another more significant dimension of contention is work. Even in the 21st Century, many mothers-in-law insist on their bahus quitting jobs as soon as they are married. This partially accounts for the “leaking pipeline” when it comes to the retention of working women across sectors. Many quit before reaching middle management. Even some of the mothers-in-law who had been working themselves, apparently impose new boundaries on their bahus. Neeta Aunty, who used to be an air-hostess zipping across countries, insisted that her bahu spend time at home, getting to know her husband rather than immersing herself in a career.

What are these homebound women supposed to do? Domestic chores. When the Austrian Carla married Ankit, her saas encouraged her to help with housework. But Carla balked at the fact that Ankit would not share in any of the tedious cleaning or dishwashing. When he was once found in the kitchen, washing dishes at Carla’s insistence, the saas chased him out with a snarky: “Do you want to wear a sari and bangles too?”

According to a survey conducted by the International Research on Women and Instituto Promundo, a whopping 86% of Indian men believed that household tasks ought to handled entirely by women. India fares among the worst countries, when it comes to the equal sharing of domestic chores. Even Rwanda, where the corresponding figure is 61%, does better. In Brazil, it’s 10%.

The intensity of such views, among men and mothers-in-law vary within India, along geographical lines. With the North, in general, being more patriarchal than the South. “In both the issues of dress code and work, the north Indian Mummy-ji takes a much stronger stance than the south Indian Amma.” But oppression or abuse cuts across socioeconomic classes. Payal, who has often walked out of her marital home because of conflicts with her mother-in-law, lives in upmarket Worli. Arti, in Kolkata, “who isn’t even allowed to sit on the sofa in her husband’s house, or accidentally step into the air-conditioned room,” is tortured not only by her mother-in-law, but also by her highly-qualified sisters-in-law: “Her three sisters-in-law are all postgraduates – one is a PhD in fact – and employed in high positions in prestigious organizations.”

What do the husbands usually do in such situations? “…his favorite strategy is to pretend that these tensions don’t exist.” Moreover, the Indian fetish for a male child extends into the mother-in-law’s obsessive attachment to her son. Mummy-ji often frames him as a flawless being, whose character is being tested by a witchy daughter-in-law.

Venugopal herself watched forty hours of saas-bahu soaps for research. Interestingly, among the daughters-in-law she quizzed, “the ones who watched the shows most keenly were the ones suffering from having the worst Mummyjis.” She also spoke to bahus across the country, getting a sense of what it feels like, to inhabit some of these households. The following two stories are among the milder and less horrific ones that populate the book:

Rachna: How I Met My Mother-in-Law

“At the movie hall, Rachna sat in between mother and son. But Gaurav wouldn’t even hold her hand because his mum was there.”

Rachna was literally wooed by her mother-in-law, even before the son entered the picture. She bumped into this kind Auntyji at a sangeet ceremony, without knowing that the lady had another scheme brewing. Over the next few months, Rachna was asked out on several lunch and movie dates, all with Auntyji. She and her roommates even started receiving five-tiered home-cooked meals on occasions. Over time, Auntyji had let drop the existence of “Gaurav” – the potential groom in London. By then Rachna was already 28 and open to the idea of an arranged marriage. She started thinking that maybe befriending a potential mother-in-law was not such a bad idea, after all. Surely that was better than not liking the guy’s mother to begin with?

Over time, Rachna was almost smothered by Auntyji’s continued wooing. Even after her son had arrived from London, Auntyji accompanied them on their first date, occupying the table next to the couple at a restaurant. Rachna found she was granted very little alone-time with Gaurav, who also seemed remarkably phlegmatic about his mother’s overweening presence. Moreover, he didn’t seem as invested in the relationship as Auntyji; when Rachna pointed this out, he was defensive about his mother’s involvement. Disregarding niggling worries, Rachna got engaged. Auntyji was gradually taking over minute aspects of her appearance – the clothes she wore on different occasions, her beauty appointments, her gym workouts. Despite such red flags, Rachna eventually married Gaurav.

Payal: The Family that Eats Together

“The secret to the longevity of joint families lies in pretending things don’t happen.”

Payal and Parag had what one would call a “love marriage.” Parag ran a car dealership in Payal’s apartment, and after a few meetings, they started going out with each other. The romance eventually blossomed into a proposal and then there was the much-awaited mingling between families. In this case, Payal’s father had warned his daughter about Parag’s parents; he didn’t think they would be an ideal cultural fit. He had brought up Payal to be independent and assertive, but he felt that Parag’s conservative family might not brook her modern views or lifestyle. By then, Payal was deeply attached to Parag, and she thought living in a joint family, in a duplex apartment setup, would not be such a big deal. She was supposed to live with Parag’s brother and wife in the upstairs flat while her in-laws were to live downstairs. This seemed like a tenable arrangement. There was, however, a catch: a shared kitchen.

The kitchen, writes Venugopal, might not have seemed like a contentious terrain to an outsider. After all, the family employed a maharaj (cook) who dished out foods according to various dietary preferences. The problem was that the shared kitchen enabled control and interference in each other’s life. For instance, Payal and her husband often liked partying late. Her saas often berated her for getting up at odd times, for going out or spending more than she needed to. Later, when Payal became pregnant, things came to a head, and there were occasions when Payal almost stormed out of the home, ready to quit the joint family setting and even the marriage.

Payal learned, over time, to temper her wins and moderate the furor. In the early days of the marriage, her saas allowed jeans, but Payal teamed it with kurtas to make it acceptable. Adopting the frog-boiling-in-water analogy, she gradually wore shorter and shorter tops, eventually moving onto sleeveless ones. Even with the tougher and more fraught battle over getting an independent kitchen, she started by acquiring a fridge. Then a stove. Till eventually, she had her own kitchen and maharaj to boot. At this point, Payal and Parag have settled into a more peaceable equilibrium, with their two daughters flitting between their apartment and the grandparents’.

Advice to Daughters-in-Law

Gleaning lessons from her interviewees, some tips that Venugopal offers to daughters-in-law include:

a) Ensure that your spouse remains supportive of your space and views. Because, according to Venugopal, “[in] many of the stories, husbands who don’t stand up for their wives often end up destroying their marriages.”

b) And it’s dismaying that something like this still needs to be articulated in the 21st Century, but “stand up for your right to have a career.”

References:

Veena Venugopal, The Mother-in-Law: The other woman in your marriage, Penguin Random House, 2014