From Adversity to Advocacy: Karthika Annamalai’s Incredible Journey

Heaving Debt and Doubts

Karthika Annamalai was only two years old when her father died. Stories swirl, to date, about the cause of his death. Relatives on Amma’s side insist he was murdered. Appa’s side is equally emphatic that it was suicide. All agree that Appa was laden with debt, and distressed about caring for his family: Amma, three kids, and a fourth curled inside Amma’s womb. Karthika was the third child, and on the day her infant brother was born, Appa passed away.

Amma had no time to grieve. Till then, inside her community, she had been considered “pampered”. Treated like a princess by her doting husband, who had shouldered the bread-winner’s role and also pitched in on household chores. But that past had dissolved and four pairs of doleful eyes tracked her movements now. She was swift and decisive in heaving her family to Bangalore, where quarry work was available all year around. Hacking stones was physically arduous under relentless glinting skies. Fortunately, there was a convent in the area, where the kids could be dropped off for the day.

And those were Annamalai’s earliest memories: of napping inside the convent, being offered milk by the Sisters. She didn’t really like milk, and she realizes later, that she had always been lactose intolerant. But she relished the cool interiors of the convent, attached as they were to a tree-dotted farm.

Driven To A New Destiny

One day, a white jeep landed at their convent. A jeep peopled with adults: a psychologist or psychiatrist, a doctor, two staff members. Karthika, her siblings and cousins, were subjected to tests.

She was just 3.5 years old then, too young to understand that the tests would propel her on a different, life-changing trajectory. Hoisting her from the thatched hut and dilapidated Government school that her siblings attended. Into what felt like an educational castle of sorts: a well-built, manicured campus, where each child was accorded a bed, three to five meals a day, and a premium education imparted by Indian staff and expat volunteers.

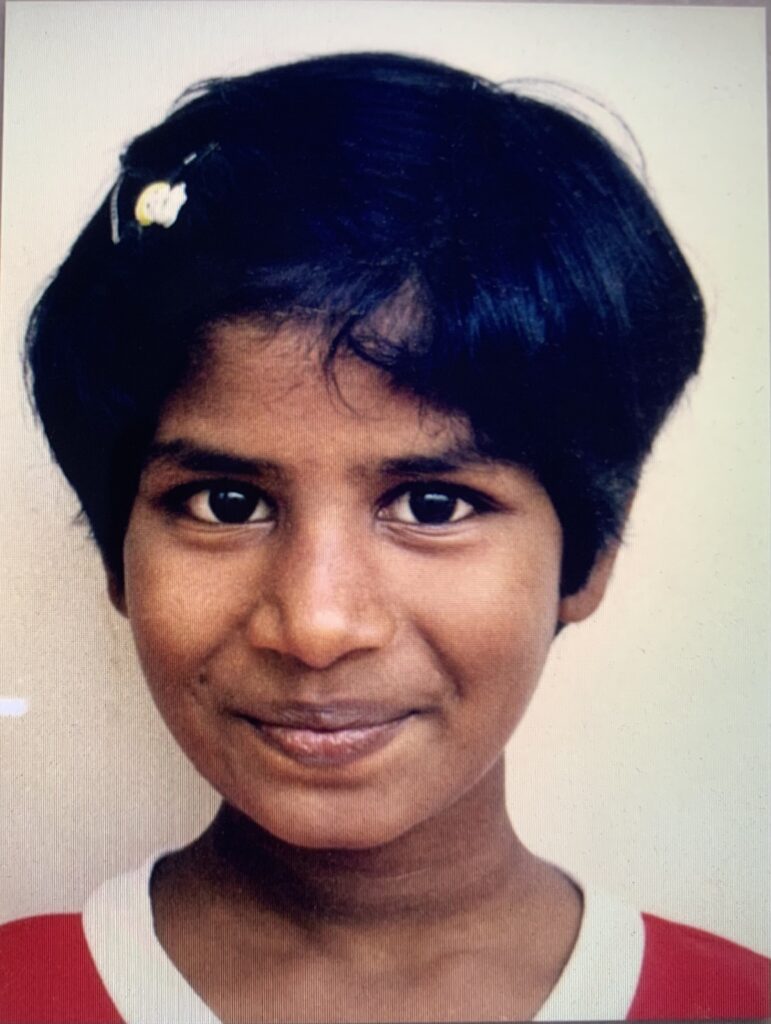

On that memorable send-off day, Annamalai was outfitted in her best dress, a white frock with polka dots, and “ugly, purple flowers” tucked inside her hair. Amma, too distraught by her child’s departure, had sent an Aunt to accompany her.

Since Shanti Bhavan, the institution that features on the much-watched Netflix documentary, “Daughters of Destiny”, had a policy of only admitting one child per family, the gap between Karthika and her siblings would balloon into a yawning chasm with each passing year. Which couldn’t be bridged merely by mastering English, or by acquiring employable skills. Like the children of upper middle-class households in India, Shanti Bhavan’s wards were tutored in the cultural codes that mark one’s standing in a hierarchical society: the vocabulary and accents, the dance and music classes, the creative and critical thinking.

Cushioned Classrooms and Harsh Homes

Annamalai was a keen learner. She soaked it all in: Newton’s Laws and Shakespeare’s sonnets, Tagore’s poems and Gandhi’s speeches. Each summer, however, she contended with the “dysphoria” between her relatively cushioned existence at Shanti Bhavan and her family’s stark deprivations. At the boarding school, water gushed through the taps 24×7, and washrooms were fitted with commodes and showers. She had toys, books, and movies to watch.

At home, Amma walked 30 minutes each way to lug back three pots of water. Everyone still defecated in fields or behind bushes. Her family struggled to cobble together a meal a day. It wasn’t just material differences. The nature of her conversations had changed in the new environment. That gap persists till today, when she visits her community, most of whom live in circumstances that have barely shifted from the past.

Beyond Charity: Advocating for Empowerment

While she’s immensely grateful to the leg-up that Shanti Bhavan has granted her, she believes that the institution should be careful about adopting a “charity mentality.” Given power differentials in the benefactor-beneficiary relationship, she suggests that benefactors should be sensitized to nuanced beneficiary needs. And accord them a greater voice over decisions that affect them.

Karthika also expresses discomfort and strong disagreement with Shanti Bhavan’s viewing of the communities they came from as “helpless”, which she believes stripped them of agency. She recalls how such a narrative led her to frame her own mother and community as incapable and lacking intelligence, despite her love and care for them. As a reflective adult, she deeply regrets holding those beliefs.

Moreover limited family visits and short vacations widened the disconnect between her and her family and community. She mourns missed opportunities for rootedness and deeper community relationships during her childhood but is now actively seeking to rebuild those ties.

And perhaps the institution should also accept that not all selectees will choose lucrative careers. For some, a job at a non-profit, or a trajectory as a teacher, nurse or musician might also beckon. She does add that team members were doing the best they could, and perhaps, they too are learning with each graduating batch.

From Bhavan to Bar

After Shanti Bhavan, Karthika cracked the competitive CLAT exam and gained entry into the National Law Institute University (NLIU) in Bhopal. Where she encountered many from the creamiest layers. Children of judges, industrialists, partners of tier-one law firms. Suddenly rubbing shoulders with wealth and power, it struck her then that the onus of uplifting her community shouldn’t rest merely with her, but with all these young adults.

While Bhopal’s law school boasted a high ranking and impressive facilities, Annamalai found the quality of education subpar. To top this, she contended with an archaic, casteist and classist mentality among some professors and fellow students, dampening her academic journey. There were cultural shocks. She was unfamiliar with foods such as momos and doklas, and her Hindi accent was distinctly Tamilian.

Fortunately, she was supported by the non-profit IDIA Law (https://www.idialaw.org/) through all this. They helped with coaching and mock tests when she set out to crack the CLAT again. Which she did. Gaining entry to one of the top three law colleges in the country – NUJS, Kolkata. IDIA also helped fund her college expenses and her living costs through internships.

Insights Into Law and Language

The West Bengal law school’s premium ranking showed because the faculty, in large part, was visibly better. In her last year, Annamalai learned about the legal aspects of impoverishment. Until then, she hadn’t dwelt so much on language and discourse. On how terming her community “poor” (a noun that saddled them with what felt like permanent deficiencies) versus “impoverished” (a verb that highlights intricate social forces that create their circumstances) makes a difference. In particular, she’s grateful to Professor Saurabh Bhattacharjee for awakening her to the legal aspects of impoverishment.

There were periods even inside NUJS when she felt socially isolated, a feeling shared by students from the Northeast. As an institution, she observes, they needed to strive for greater inclusion. Karthika noticed that “quota” students drawn from SC/ST backgrounds were housed in crowded dormitories, infested with rats and pests. During in-class conversations, she often felt like a lone voice expressing the viewpoint of the marginalized, without sufficient backing from professors.

From Corporate Law to Legacy

After NUJS, she landed at AZB & Partners, a tier-one law firm. She gained entry into such a competitive space because she also “interned like crazy,” utilizing all her breaks to garner workplace smarts. Her first year at AZB was both challenging and exciting. Moving to Delhi, and unfamiliar with its harsh winters, she landed up at the office in sandals. Soon, however, she stocked up on scarves and sweaters, acclimatizing like all others to a tough city and job.

Over time, though, she realized she was burning out inside a demanding work culture. Intense work hours and a lack of work-life balance induced mental and bodily fatigue. For Annamalai, the exhaustion was multiplied. Even on vacations, when she returned home, her family still lived without basic amenities. Working on mounting generational debt first, she hadn’t saved enough yet to move them to a better place. Something that she was able to do two years after joining AZB.

At the end of four and a half years, she shifted to a boutique law firm, Rajaram Legal in Bangalore. She cherishes fond memories of her time there. Founded by a woman leader, Archana Rajaram, the firm had everything an idyllic workplace should possess. Respect for the personality, quirks and dignity of each human being. While the work performed was as high-stakes and as exacting as that of tier-one law firms, Rajaram Legal managed to inject it with fun and camaraderie.

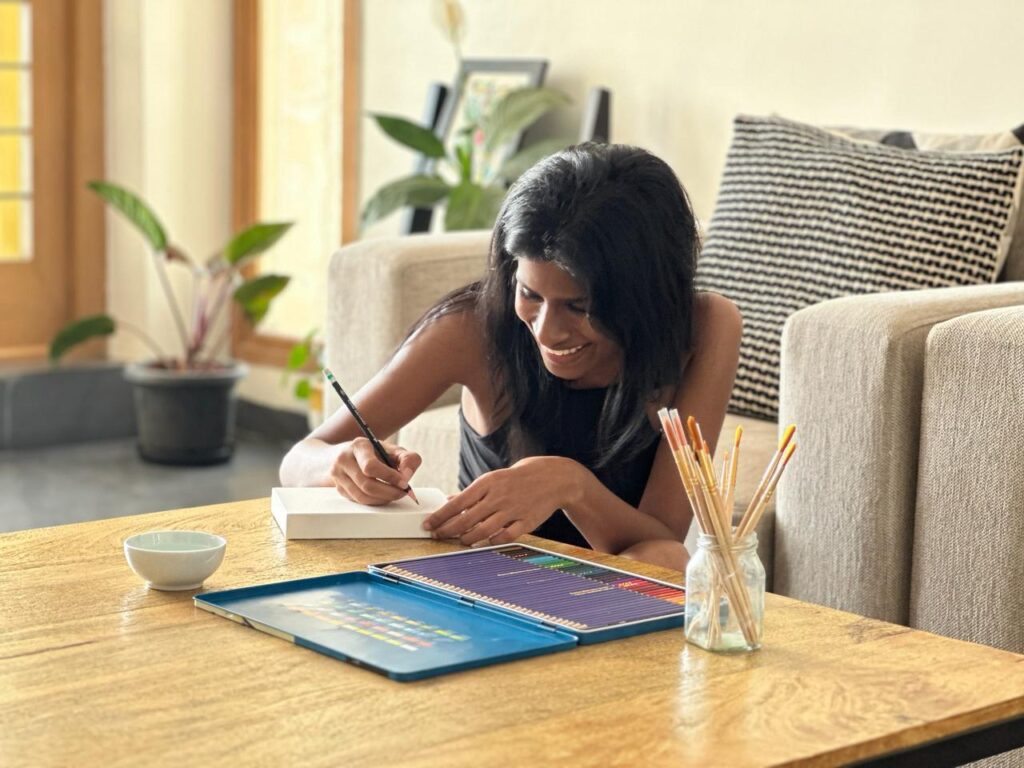

At the end of two fulfilling years in the firm, Karthika realized she needed to pursue a different career. Corporate law did not feel as appealing in practice and wasn’t leading her towards her broader goal: to make a difference to her community.

Gleaning Insights into Schooling

She moved to Ekya Schools as Chief of Staff, where she was stirred by the founder’s vision and by the impact of Ekya’s eleven educational institutions. Like at Rajaram Legal, she was drawn to the female leadership of Ekya Schools under the dynamic Tristha Ramamurthy. She continues to thrive in her new job, where she shadows the founder and gleans insights into the complexities of running schools. She’s in awe of teachers, who need to make 30 to 50 snap decisions every day. “More than a CEO,” she observes.

Transforming Her Community

As exciting for her personally, she has been able to move her family to a larger home, with all the trappings of a middle-class family. Including a large lawn. Careful not to suddenly alienate them from erstwhile neighbors, she picked a place that’s proximal to the quarry. Her mother can still walk over to meet acquaintances. But she no longer has to heave pots of water.

As Annamalai’s grown, she also appreciates Amma’s traditional knowledge, as she perhaps didn’t as a child. “She can survive in a forest. She knows what plants can be eaten. She knows how to apply first aid in case of a snake bite. She knows how to care for her children, and community, and to take that chancy decision to send one child to a remote boarding school.”

Beyond her family, Karthika aspires to usher changes into the larger community. But she plans to do this in a thoughtful manner, with a deeply felt sense of how social engineering is complex and often fraught. She wants to do this in partnership with community voices, according them a rightful agency in determining their own futures.

From abroad in the U.S., we are rooting for you Karthika!

Karthika vous aviez toute mon administration depuis la France. Espérant rencontré la belle âme que vous êtes un jour. Je souhaite à votre famille spécialement à votre maman une longue vie pour voir la meilleure que vous êtes et les grandes choses que vous accomplirez pour elle et votre.communauté.

Just watched Daughters of Destiny on Netflix today, and then googled Karthika… Such an inspiring life…. Amazing work by the people at Shanti Bhawan ….teachers, founder…support of her parents. Truly truly inspiring….would love to meet Karthika one day. Thought she might be working here in Delhi, but it seems she’s in Bangalore. All the best…. would love to see her as a PM President as she mentioned.