When an MIT Philosophy Professor Has a Midlife Crisis

In the 1999 film, American Beauty, the protagonist Lester Burnham embarks on rather stereotypical responses to what one might term his midlife ennui. He trades his unexciting Toyota Camry for a zippier 1970 Pontiac Firebird, and lusts after his teenage daughter’s best friend.

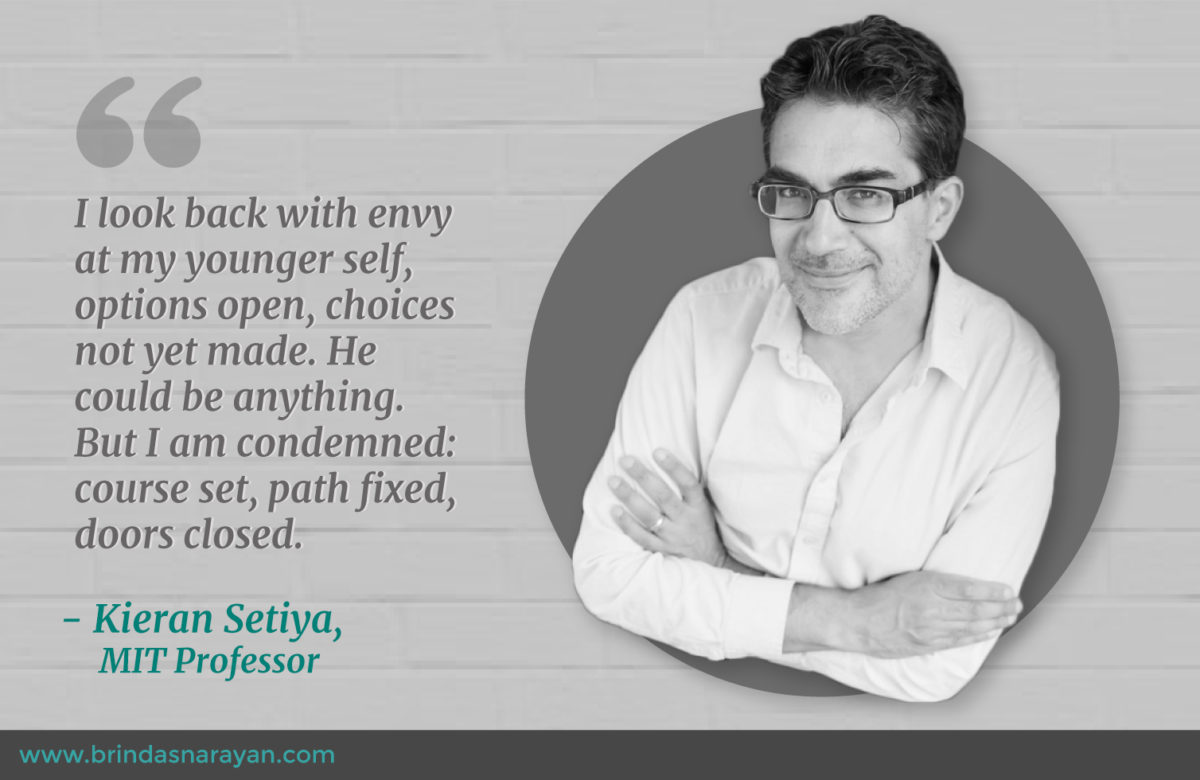

Kieran Setiya, who is currently a philosophy professor at MIT, rejects such a cliched return to adolescence – a sports car, an extramarital fling, marijuana or an impulsive career change. In his book, Midlife: A Philosophical Guide, Setiya journeys through his own ‘crisis’, using the frameworks and tools of his field, to analyze both the causes and answers to a decline in satisfaction that marks midlifers across geographies and cultures.

It is of course, both puzzling and ironic, as the Prof himself points out, that he even seems to face a crisis. After all, he seems to have it all: financial stability, a peaceful marriage, a child, and a tenured position at a prestigious university. He even thinks his career choice is best suited to his temperament and intellectual proclivities. Yet he senses futility in his actions – publishing more papers, writing more books, teaching more students. In other words, more of the same.

He’s aware that the feeling is engendered by a sense of his own mortality. After all, at midlife, despite whatever we do to camouflage the signs of aging – dye our hairs, fix our teeth, botox our wrinkles, replace our knees – we cannot hide the stark fact of our own inevitable deaths. On the other hand, the idea of living forever, even in perpetually youthful bodies, does not hold appeal. How would we deal with the tedium of infinity?

A Social History of the Midlife Crisis

Before shining a light on his personal dilemma, Setiya charts the history of the ‘crisis’ as a social phenomenon. The midlife crisis is a modern, 20th Century notion. The idea of midlife representing a low-point did not exist in popular American or global lexicon, till Elliot Jacques used the term, for the first time, in his 1965 essay titled “Death and Midlife Crisis.” In the earlier century, midlife was largely perceived as a pinnacle in life satisfaction, because one was assumed, by then, to have achieved a certain mastery or competence in one’s field.

In her book, In Our Prime: The Invention of Middle Age (2012), Patricia Cohen conjectures that the increasing mechanization of work and the adoption of industrial measures like ‘productivity’ and ‘efficiency’ may have led to a devaluing of older workers, as companies demanded the stamina and energies of younger bodies. Moreover, the large-scale unemployment of older workers during the 1929 American Depression strengthened the categorization of such people as ‘unemployable.’

After Jacques’ iconic article, the sense of a ubiquitous crisis was perpetuated further by the bestselling book, Passages: Predictable Crises of Adult Life (1974) by Gail Sheehy. Through the 70s, most members of the American public believed the crisis was widespread. To confirm this, in 1989, the MacArthur Foundation commissioned a large-scale study to verify the anecdotal evidence depicted in books and articles. Surprisingly, they reported it wasn’t significant. A later study found it seemed to afflict only a quarter of American midlifers. Though a quarter still comprises a reasonably large population, when the results of the decade-long study were published, a Washington Post article carried the headline, “Midlife Without the Crisis.”

But after psychologists had lost interest in distressed midlifers, in 2008, two economists (David Blanchflower from Dartmouth University and Andrew Oswald from the University of Warwick) revived the idea of a more pervasive crisis. Studying a much larger population across 72 countries, they discovered a “gently curving U”, a shape that held across genders and cultures. They found that people were generally happier when younger and when older, but less so at the “crest of the hill.” Later, similar curves were observed among great apes (including chimps and orangutans), indicating not just social or cultural, but biological drivers.

Lessons from the Lives and Thoughts of Early Philosophers

Accepting the inevitability of such a crisis for most midlifers, Setiya digs into the lives of earlier thinkers like John Stuart Mill. Mill, who was schooled by his father at an extraordinarily intense pace, was by the age of twenty, already a significant contributor to British philosophy and political economy. However, just when he had already achieved more than other young adults of his era, Mill suffered a nervous breakdown.

Like Setiya, Mill decided to analyze his own crisis. His first conclusion was that one needs to have an object (or purpose) in life besides the pursuit of one’s own happiness. In other words, Mill felt that happiness should always be a side-effect or by-product of some other striving. He also spent time reading the poetry of Williams Wordsworth and gleaned from the poet’s words, that there was value in tranquil contemplation. Mill realized that one should not only pursue activities with ameliorative value (leading to improvements in the world or gains to the self), but also in activities with existential value (like just thinking about a beach or watching honeybees).

The German thinker, Arthur Schopenhauer, separately ruminated on the irony inherent in outcome-driven projects. After all, outcomes are a manifestation of desire. A person without desire might be bored with everyday tedium and the lack of change or movement. On the other hand, the person with desire is also inflicting pain on one’s self. After all, desires, till met, seed dissatisfaction. So, Schopenhauer concluded that one is doomed to swing between ‘boredom’ and ‘dissatisfaction.’ While this may not be limited to midlife, the tugs between the status quo and novelty at this stage, are more deeply felt.

Impulsive Changes May Not Be the Solution

While Setiya believes that it is not too late to embark on a career shift at midlife, he warns against change for its own sake. He notes that “the appeal of change itself can be deceptive.” In a 1970s British TV series, a middle-aged man fakes his own death, quits his job and flees his family. He then returns to the same life, but this time, he’s newly energized because it seems to be of his own choosing. Setiya observes that a hankering for change might represent a yearning for an earlier stage in life when one had more options. That sort of nostalgia for a past filled with choices is an inevitable human condition. However, while regretting certain decisions or paths taken, we are unaware of the details of unchosen lives. We do not know the nuances, or the “fabric of everyday existence,” and hence some of those untrodden paths might have been the wrong ones anyway.

Even Setiya, who at one point, wanted to be a poet, and then a doctor, but eventually settled on teaching philosophy, does not believe he’d have been happier in those other professions. Yet he’s conscious of a persistent dissatisfaction or emptiness in his current life. Extending the thoughts of Mill and Schopenhauer, he also turns to Buddhist philosophy and even to the famous dialogue in The Bhagvad Gita, where Krishna exhorts Arjuna that “motive should never be in the fruits of action.”

The Professor’s Prescriptions for A Fuller Midlife

Setiya concludes that the solution to his crisis lies in paying more attention to the present without seesawing between nostalgia for the past or yearning for the future. He distinguishes between his work-related projects, which he describes as being ‘telic’ (or goal-driven) in nature. (Telos is the Greek word for end). Since his work is outcome-based, his work-related tasks are self-destructive. Each time he reaches an outcome, the project or activity ceases to have further meaning. For instance, in the case of his teaching, if a particular batch of students have been taught, that job is ‘finished’ till the next batch arrives. Similarly, an article or book, when published, no longer fills any ongoing purpose in his life. After the euphoria of achievement fades, one faces a recurrent dissatisfaction or boredom.

He decides then, that he must consciously engage in atelic activities as well – for instance, taking a walk in the park, or conversing with friends, or playing a game or pursuing a hobby. The ideal solution, would be to also reframe his work-related ‘telic’ activities into ‘atelic’ ones – to pursue them for their own sake, regardless of outcomes. Steve Jobs also enjoined his audiences to pursue work for sheer pleasure, when he said, “the journey is the reward.”

While Setiya’s injunctions can work well for someone who does not strongly feel that a different career (or some other form of change) is necessary to experience such pleasure, his directives are less fitting for those who need to change the “what” in order to change the “how”. How can one usher changes at a stage when everything is precarious: family finances, relationships, viability of an alternate career? Or when a crisis is thrust on you? Since midlife is a cultural terrain I happen to inhabit, I am intrigued by the evolving contours of its landscape and shall explore this and other questions in future posts.

Bibliography

Setiya, Kieran, Midlife: A Philosophical Guide, Princeton University Press, Princeton, 2017.

Cohen, Patricia, In Our Prime: The Invention of Middle Age, Scribner, New York, 2012.