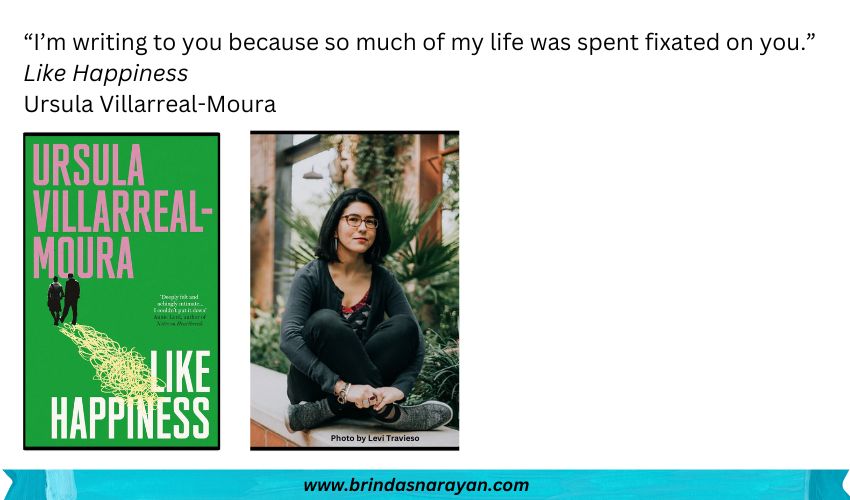

Like Happiness: The Mirage of Connection in a Post #MeToo Era

Like Happiness begins with a New Yorky scene. One that captures the stickiness and muck and strangely alluring grit of its subway rides. But also the forced physical proximity to performers whose music and moves are edged with aggressive asks. In this case, boom boxing teens whirling too close to the protagonist, as she scrutinizes her mascara in a compact. The song they are blaring is Michael Jackson’s “Billie Jean is not my lover…” Apparently, Jackson penned those words in response to fervent, escalating letters from a fan who claimed that the singer was the father of her twins. Despite his stoic silence, she kept writing in, eventually dispatching a gun and a death threat.

The protagonist Tatum Vega is also writing a letter. To a prominent Latino author, Mateo, with whom she has been entangled in a strange, complicated relationship. We listen then to her narration in the second person, the “you” being both Mateo and the reader. With the latter feeling like her sometimes confessional, sometimes finger-pointing recounting of the past is addressed to someone specific and diffuse. We are complicit then in the doings of Mateo, in the somewhat menacing thrum of such relationships.

Which started out when Tatum was a senior at Williams College, when feeling like a misfit inside the preppy, predominantly white liberal arts institute. Growing up as a lonesome reader in Texas, where she couldn’t relate to the Bible-loving, church-going sanctimony of her Mexican parents, she had always pictured Massachusetts as an exalted place. The State having spawned her favorite writers: Sylvia Plath, Emily Dickinson, Anne Sexton, Robert Lowell and others. She was sure then, at high school, that she would find her tribe at a place like Williams. In the picturesque setting with Cambridge/Oxford style tutorials and enticing proximity to writerly greats.

Choosing to major in English, she quickly realized how white the canon was. Even the problems being addressed in those novels felt trivial and unrelatable: “Almost 100 percent of the novels I was assigned dealt with Europeans experiencing romantic strife or ennui because they were bored with tea parties, or they disliked a neighbor or family member.”

At a D.H. Lawrence spring seminar, she was struck by how the author treated all his characters with disdain. In particular, a Mexican character named Geronimo Trujillo, renamed “Phoenix” to slide easily off white tongues, was dissected by the class without any references to the author’s racism. No one brought up how Lawrence had objectified Phoenix. A pearl-wearing, blonde peer summed it up: “Phoenix has skills but is disposable.” All along Tatum squirmed in her seat, her fury turning against her own cuticles, which she ripped into a blood-smearing rawness. Did anyone sense she was Mexican? Did it matter?

In this isolated, vulnerable state, she stumbled on “Happiness” – a novel by Mateo that has her taking it in like one would with a secret drug. In doses, in a blankety privacy, apportioning its pages to draw out the thrill. The elation of discovering someone who seemed to know her, speak to her, speak for her. In typical fangirl fashion, she dashed off a fawning letter to the author, expecting to be ignored. After all, Mateo by then was a legend, a heavy weight, who despite or even because of his Hispanic heritage, had the mostly white literati salivating at his sentences. He writes back. She writes again, he replies. And so on, till they switch to email and telephone conversations. Then he wants to check if she’s single. Tatum does not spot the red flags. She’s infatuated, and Mateo fills a void in her life.

This is a post #MeToo novel. Except that it’s not a black and white depiction of an abuser and the abused. Quite early in the novel, after their relationship has ended, and after Tatum has moved to Chile with a partner (in the process of coming-of-age, she also identifies as queer), she receives a call from a New York Times reporter. Who wants to interrogate her about her relationship with Mateo. Tatum is tempted to speak out but she hesitates. The journalist tells her that the once-worshipped writer has been accused of sexual assault by another woman. Online pictures confirm that Tatum had some kind of relationship with him. Tatum then reflects on that past, on herself and him, and she can relate to what the abused woman claims: “You weren’t that person with me, not exactly, but the fingerprints of our stories are strikingly similar.”

Ursula Villarreal-Moura dwells on the greys, on the ways in which Tatum might be complicit in this relationship. The power dynamics are imbalanced, as they often are in seemingly successful partnerships. Here’s an older man who’s adored by a protégé that he seems to “groom”, without her realizing that she’s stepping into a well-known trap. Just as love can foster unhealthy dependency and stoke delusions, it can also feel like a refuge. If you’re someone who’s experienced manipulation or a sense of being used, reading “Like Happiness” might compel you to say: #MeToo.

References

Ursula Villarreal-Moura, Like Happiness, One, Pushkin Press, 2024