Voyaging From a Village to Becoming a Co-Founder of 100x Entrepreneur: Nansi Mishra’s Uplifting Story

Early Childhood in Devkali

The village of Devkali in Uttar Pradesh is located in the district of Shahjahanpur. Spanning an area of about 6.5 square kilometres, with a population of about 3035 people, it can almost be viewed as an idyllic counterpoint to the teeming density of Bengaluru. Nansi Mishra was born there, to a farmer father and homemaker mother. Although they inhabited a fairly big house, it was tightly packed with members of seven or eight families. Her father and his three brothers were dependent on their farming income. “We had just enough land to survive,” as Mishra puts it.

Along with her cousins, Mishra too started attending the village school. But her mother, whose father had been a primary school teacher, seemed to detect a certain breezy approach among the school-going lot. After all, expecting to turn to farming in the future, they could hardly treat their textbooks and exams with any kind of earnestness. How would Newton’s laws help them till their fields or water their crops? But her mother had a different kind of foresight as well. At the very least, she wanted her kids to be well-educated. She persuaded her husband to bag a job at a fertilizer factory at Shahjahanpur, a small town or tier-3 city, where they could access a better school.

Schooling in Shahjahanpur

In the town, named after the fifth Mughal emperor but sans the grandeur of his kingly courts, Mishra resolutely took to her books. She knew how her parents’ yearnings were yoked to her own future. Of how her father painstakingly jotted entries about outgoing trucks at the fertilizer factory, so that his kids could benefit from more esoteric economies.

Though the school was private, the medium of instruction was Hindi and the facilities were barebones. Without the kind of infrastructure that contemporary big-city, upper income kids are endowed with – a plethora of tutors and extracurricular classes – Mishra received commendable results on her U.P State Board Exam, ranking among the top 10% in her school.

When Mishra had completed her 11th Grade, her Bua (father’s sister) who lived in Ghaziabad, proximal to Delhi, persuaded her to move to the larger city. Her Bua sensed that Mishra had immense potential, but could hardly leverage her talents in a small town. She suggested she enroll at a school at Ghaziabad for her 11th and 12th Grades. By then, Mishra too had realized that she needed to acculturate herself to the larger city’s slang; to the kind of lingo that her city-bred cousins effortlessly tossed around, but were still foreign to her. For instance, when they casually said things like, “Let’s book a cab,” Mishra would ask: “What is a cab?”

Cities, as the social theorist Ashis Nandy observes in An Ambiguous Journey to the City, have always played more than a functional, economic or social role in the Indian imagination. They also occupy what he terms a “mythic status” – imbuing incoming migrants not only with wider opportunities, a liberating anonymity, heady metropolitan experiences but also the tongues and speech styles of the one-time colonials. Or, in contemporary times, the argot of the startup economy, the flair of the technology crowd, the methods of the media-savvy.

Landing an Internship in Delhi

With the same determination that had driven her to the top of her school, Mishra started learning the ways of Ghaziabad. Unfazed by the linguistic hurdles – for instance, when a friend asked “Where are you put up?” she did not know the unfamiliar idiom referred to her home address; still, by asking questions of her city-bred cousins and observing everything around her with a wide-eyed curiosity, she started absorbing the nuances. Overcoming the embarrassment of a newcomer, by the end of Class 12, she had forklifted herself to garner 91% on the Board Exams. Thereafter, she was admitted to Delhi University for a B.Com (Honors) degree.

Continuing to soak up the ways of enterprising go-getters, she realized that many of her peers were landing internships during their degree program. She downloaded the internshala app on her phone and filled in her details. She was afraid she wouldn’t land anything, because most positions seemed to insist on “Excellent Communication Skills” – which was a euphemistic way of saying “Excellent Communication Skills in English.” But her enthusiasm was palpable, infectious even. So much so, that the team at Babygogo – a platform for mothers and babies – hired her. She still describes that three-month internship in a coworking space – where she encountered other startup teams like Joshtalks – as one of the most thrilling phases in her life.

Her internship involved talking to about 50 to 60 mothers every day, trying to discern what they would seek from an app like theirs. Perhaps, inadvertently, Mishra was already getting sensitized to the peculiar concerns faced by parents, and mothers in particular. After her college degree, she joined Babygogo as a full-time employee. Eventually, the startup was acquired by Sheroes. She was also married by now (to the ex-CEO of Babygogo), and she and her husband, Siddhartha Ahluwalia, were awarded full-time positions in the woman-focused Sheroes.

Building a Women’s Community

Mishra’s job involved building a community centered around women’s health. Her team invited expert guest speakers – like doctors – who would conduct sessions on menstrual health, oral health, sexual health, and other topics that were often not discussed in many Indian households. She wrote articles, at this point, of her upbringing, of the manner in which her mother used to be sequestered during her menstrual cycle and made unavailable to her children. Mishra described how bewildering that was, and in retrospect, how unnecessary. She realized such communications among women-only communities bolstered the voices of those who felt like misfits inside traditional spaces, but hadn’t encountered like-minded cheerleaders so far.

Contending with a Startup and a Baby

After a couple of years at Sheroes, she and her husband moved to Bengaluru and founded 100x Entrepreneur, a podcast. They intend for the podcast to become India’s #1 in the startup and investing space. Already sponsored by Prime Venture Partners, Mishra and Ahluwalia have plans to grow the channel in multiple directions. They have also learned to constantly reconfigure the makeup of their programs to cater to listener needs. At first, they hosted many venture capitalists. But then they realized that they also needed to incorporate Founder journeys. Even while broadening their offerings, they ensured consistency by posting at least one episode per week.

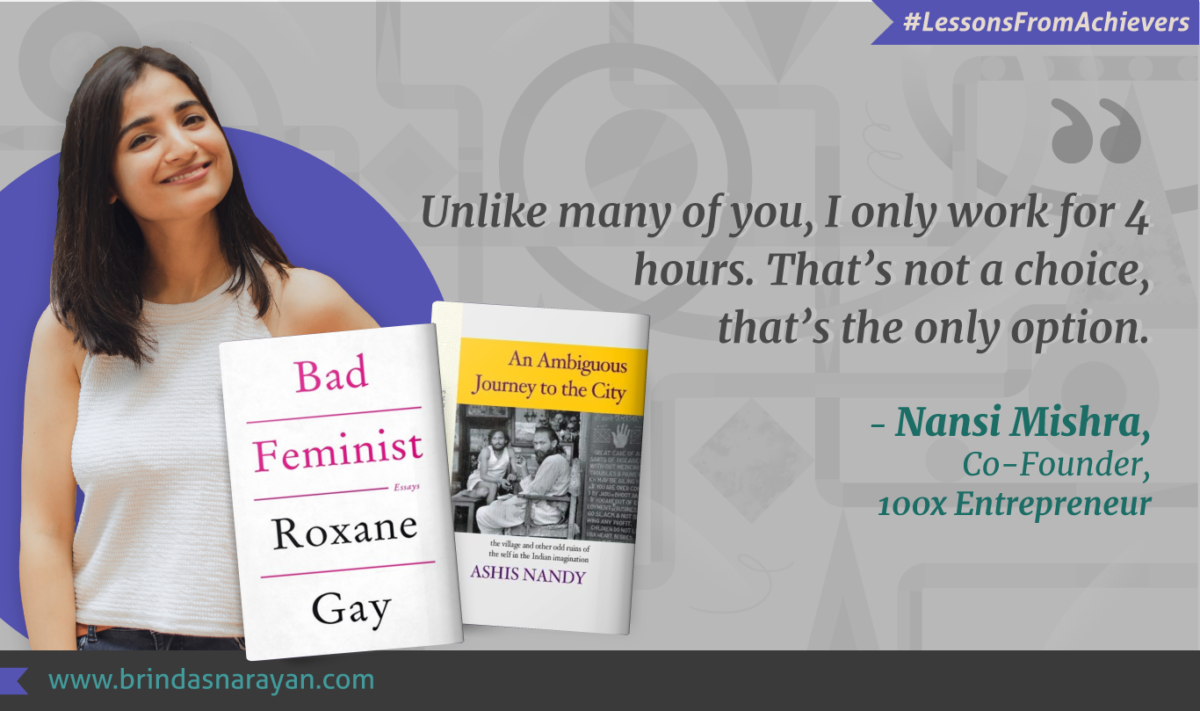

In the meanwhile, as a working mother, Mishra was also attuned to the other tugs on her time. In a heartfelt and pithily-worded post that went viral on LinkedIn, garnering more than 400,000 likes on the professional platform, she said:

“Unlike many of you, I only work for 4 hours. That’s not a choice, that’s the only option.

Being a mother of a small baby, I can’t be in one room working all day or anytime while the baby is crying outside longing for her mother. With the help of my family, I manage to take out some time.

But in that 4 hours, I make sure I am most focused and most productive because my baby is letting me work so that his mother can follow her dreams and doesn’t give up on the dreams his mother’s mother had for her ❤”

Since then, Mishra has also been designated as one of the “LinkedIn Top Voices 2021: Next Gen”, for candidly expressing sentiments experienced by many working mothers. For being, as well, a role model who was dauntlessly willing to confront her own situation and put it out there, in a manner that resonated with many.

From Bad Feminist by Roxane Gay:

With a similar kind of candor that has marked her out as a voice for people who cannot be boxed into facile categories, the writer Roxane Gay admits: “If I am, indeed, a feminist, I am a rather bad one.”

In her iconic essay titled “Bad Feminist,” Gay cites her favorite definition of a feminist. Gay herself borrowed this from an anthology titled DIY Feminism, that featured an interview with an Australian woman named Su. As Su simply puts it, feminists are “women who don’t want to be treated like shit.”

Gay argues that just as there is no essential way in which to be a woman, there can be no essential way to be a feminist either. For instance, a woman who likes to wear make-up, dress glamorously and even chooses to be a caregiver or homemaker, can belong unapologetically to the feminist tribe as much as a passionate career woman, as long as she subscribes to the notion that women should be making these choices of their own accord.

Gay observes, that for too long, feminism has been associated with certain pigeonholed ways of being: “anger, humorlessness, militancy, unwavering principles and a prescribed set of rules for how to be a proper feminist woman.”

She then candidly lays out some of the contradictions in her own life or persona. While she relishes her independence, she also cherishes having a partner who cares for her, whom she can return home to. Given that strong women are perceived as people who are not subject to emotional outbursts, Gay admits to occasionally giving into the opposite impulse: “Sometimes I feel an overwhelming need to cry at work, so I close my office door and lose it.”

Then there are other confessions. She loves reading Vogue, and not even with the eye-rolling irony that might be expected of an intellectual (and “feminist”) like her. She loves pink, in all its blushing, effeminate shades and much prefers it to black. She is ardently fond of dresses and of dressing up, with her legs shaved. She claims to possess an outright ignorance about cars, apart from being able to drive them. More than that, this is not a void she intends to fill. It’s an aspect she is delighted to outsource to expert mechanics, female or male. She admits to other Cinderella-type fetishes: “I love diamonds and the excess of weddings.”

She also says that she would really like to have a baby, and to slow down her career in order “to spend more time with [her] child.” She likes men, even as she abhors misogyny. Yet, she realizes that a thinking woman like her cannot abandon a movement that has imbued her, as it has other women, with rights that were inconceivable to women in previous generations: “I would rather be a bad feminist than no feminist at all.”

Growing 100x Entrepreneur

While still straddling her parental role, Mishra is animated about the future of 100x Entrepreneur. So far, the podcast has already featured many of the marquee names in the startup space including: Vani Kola, Managing Director, Kalaari Capital, Harsh Mariwala, Founder and Chairman of Marico, Sanjeev Kapoor, Founder and Celebrity Chef, Karan Bajaj, Founder of WhiteHatJr. and Author of bestsellers like Johnny Gone Down. Mishra admits that getting such prominent people to feature on the podcast has involved many uphill struggles. Of course, once the team had a few of the highly-reputed voices endorse their platform, others were easier to convince.

Besides hosting enlightening conversations, they have also added Master Classes with Growth Experts. Mishra is also focused on the distribution pattern, constantly scanning the data to discern growth opportunities for their channel. With a deep-seated empathy for the linguistic hurdles faced by fellow-Indians, they also plan to expand their offerings in Hindi, and maybe eventually consider other Indian languages.

References:

Ashis Nandy, An Ambiguous Journey to the City, Oxford University Press, New Delhi, 2001

Roxane Gay, Bad Feminist: Essays, Harper Perennial, New York, 2014