Shining a Light on Crime and Caste

For those who wish to pick up this book, let me start with the ritual “spoiler alert.” I’d also like to add, that to uncover “who’s done it?” is probably not the only reason to read this. The author herself seems less invested in surprising readers with unforeseen twists, than in revealing the gritty underside of a roiling nation.

Before reading this, I thought the era of employers being able to pin crimes on staff – usually on hapless drivers – might have passed. After all, can you really get away with – in this case, literally – murder, in the midst of CCTV cameras, and so many witnesses, all equipped with watchful, recording devices? Clearly, there are places where you can, as Anjali Deshpande, observes in Nobody Lights a Candle.

One needs only to drive into the outskirts of cities, or to the peripheries of towns, to remote farmhouses nestled in villages, where the community’s fear about getting involved with the police will pretty much gag witnesses into silence. Even if those folks don’t fear the police, they fear the powerful, whose invisible connections form a spidery net, from which the rich bounce back, but the poor fall into.

Deshpande infuses her detective, Adhirath, with a likeable surliness. He has reason to be irritable: as an ex-cop who’s been suspended from service for fudging records to save a subordinate. And that poor subordinate (a constable) had shot a well-known rowdy sheeter, someone that Adhirath had been yearning to nab but couldn’t, because witnesses turned mute at the sight of gruesome crimes. Like the throat-slitting of a young boy waiter, who was merely sloppy in serving dhal, spilling a few drops on the table.

Net-net, Adhirath is now at home, with his less likeable parents, his father, patriarchal, casteist, drunk and spraying curse words; his mother, equally vinegary to Adhirath’s wife, Pushpa, who’s from a lower caste. Who also works on the police helpline, and at this point, earns more than her suspended husband. “His mother talked of the rising cost of living, his father of Pushpa’s reluctant performance of chores.”

Deshpande details domestic scenes with psychological astuteness. Like the way in which Pushpa’s in-laws keep bringing up her caste, every now and then. Since Adhir and Pushpa had a love marriage, parents hurl insults at both. At him, for marrying her. At her, for being who she is. Like most women, the bahu finds verbal duels tiresome. “Pushpa rarely spoke in the downstairs room unless there were guests. Her pots and pans spoke and they said a lot of things. The tawa getting off the stove, the pressure cooker letting off steam, spoons stirring inside pots, water being poured into jugs, every utensil spoke of the mood of bahuji.”

A bored Adhirath, who doesn’t have much to do besides dropping his son off at school, hears of a woman murdered in a farmhouse. He’s not officially assigned to the case, but he’d like to keep his grey cells ticking. And find a reason to abscond from his house and the ongoing bickering between his parents and wife. Besides he lives in the kind of place, where working from home is akin to working from hell: “All around him were neighbors, gargling, abusing, spitting and staring. On the road were cars and cycles and cycle rickshaws, vegetable vendors and the sound of people haggling for pennies.”

Confrontations between village folk and the police do not yield anything. The sobbing mother of the murdered girl – she was young, working as a beautician in a salon – begs Adhirath to find the murderer. Admitting, at the end of her plea, that she wasn’t a “good” girl.

Adhirath’s uncle-in-law (Mamaji) performs autopsies. He caustically remarks that upper castes become doctors, but have nothing to do with the bodies that land up at the morgue. The “dirty” job of dismembering the dead and diagramming causes is assigned to those at the bottom of the social ladder. When Adhirath enquires about the girl who died at the farmhouse, Mamaji says she was strangled. But also that her abdomen was gashed in a straight line, precisely, as if with a ruler.

Adhir accompanies his policeman friend, Nitesh, on his investigations. Through all this, Deshpande threads her social commentary, as one often can in crime fiction, more than in other genres. Like the patriarchy that runs through the police. Of the murdered woman, Nitesh says: “She was a whore, a bitch.” After all, she worked in a beauty parlor. And everyone knows how certain massages are given, behind curtains. As Adhirath notes later, “A man’s lust and lecherousness are legitimate but in a woman the same appetite turns into sin.”

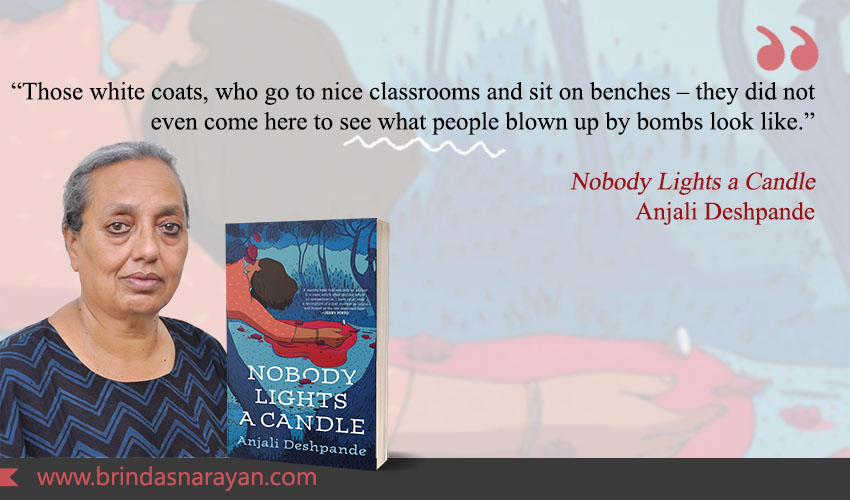

The book doesn’t end on an optimistic note. Justice is not served. A major villain is off the hook. The idealistic Adhirath is not reinstated into the police. Yet, as messy as Adhir’s marriage might seem on the surface, he and Pushpa are clearly in love. Relationships like theirs might be the only means to diffuse the stranglehold of caste. In all that darkness, there’s hope too. Written originally in Hindi, and translated into English by the author herself, Nobody Lights a Candle offers glimmers into what is and what can be.

References

Anjali Deshpande, Nobody Lights a Candle, Speaking Tiger, 2024