Thrilling Tales From The Ticket Booth

Countless books feature train journeys across the variegated landscapes, towns and villages that stitch up our nation. Platform Ticket is different. It shines a rare light into a world that many travel writers fleetingly brush against: the cramped, grilled, sometimes smelly or cockroach-infested spaces from which a motley crew of indefatigable railway staff perform the numerous operations that keep our trains clacking and squealing across the world’s fourth largest network. The effervescent Sangeetha Vallat spent 14 years behind those counters, issuing tickets, collecting and giving change, filling book registers, computing fares while also conversing—yes, magically enough—with hundreds of impatient, beseeching or churlish customers.

Getting Hitched to a Railways Career

As a child, Vallat harbored a different dream: she wanted to read books. Not foreseeing a future where reading could earn a living, she opted to join the Railway Network. As the only one in her school to clear the Railway Recruitment Board (RRB) exam, she entered a two year vocational course along with her Plus 2, held inside a posh institution that seemed to signify a rosier future. Because of bureaucratic snags, she had to wait longer to receive the coveted brown envelope, confirming her Government job. To her youthful glee, the letter accompanied a free Railway pass printed on striking pink.

Dispatched to the Line’s Dusty End

At 20, she was posted to a small station, 424 kilometers from Mysore, at what felt like a bleak, deserted platform. At the small eatery – the only visible sign of life there – Mr. Shetty of Shetty’s Vegetarian Light Refreshment was stunned to hear that Sangeetha was the new Railway clerk: “You are the first lady employee in our station!” Her parents accompanied her and her Amma intended to stay on inside the spare Railway quarters. To bolster her security and also help with everyday chores like cooking on their kerosene stove.

Being Tongue-tied and Other Trials

Her workplace—‘barebones’ can hardly describe it—consisted of a blackboard and a grilled opening in the wall. Furthermore, as a Malayali raised in Chennai, Vallat didn’t speak a word of Kannada, the lingua franca of a picturesque town that was poised to test her spirit in unexpected ways. Luckily, she had friends from her cohort, who were posted at different stations. Sporadic meetings and phone chats boosted each other’s morale. She heard of her friend, Balaguru, who also fumbled in Kannada. Once, he infuriated a female customer by saying “Ganda odisu mele ticket niduttene (Once the husband beats you, I will issue a ticket) instead of “Ghanta odisu mele ticket niduttene” (Once the bell is rung, I will issue a ticket).

Such linguistic faux pas were less droll during the Cauvery water disputes. A colleague was saved from an unruly mob by a quick-thinking friend who convinced the lathi-armed crowd that he was deaf-mute (he wasn’t). Another watched a snake slither across his makeshift pillow – of registers and books – on a strenuous night shift. Such tales were exchanged at reunions to celebrate birthdays, sing, watch movies and cook together. Even years later, as adults who’ve moved on from their railway postings, they meet at resorts and play “train”: “Unmindful of the staring guests all over the resort, we do the winding railway engine, bogies, guards, etc., screaming ‘Kooooo chug chug choo choo…’”

Experiences at these forsaken and desolate stations – some at mofussil junctions, some in the middle-of-nowhere expanses, some in single-storey buildings that seemed designed for “horror movies” – were not just bleak. Or tedious.

Sparks Fly by the Tracks

On rain-lashed nights, when the power dies out and candles lit to keep the operation flickering, romances blossom. Sangeetha admits to a crush on a married boss, whose “Adonis” persona was irresistible inside the confines of their tight-knit workspace: “He never issued tickets but watched me work. I said it unnerved me to be watched, he chortled and came closer.” Once she rode pillion on his yellow scooter, intentionally donning a matching yellow kurta: “An electric burst coursed through my body. Sometimes I wondered whether it was the scooter or the SM I had a crush on.” As the only woman in the station, Sangeetha reveled in the attention of “men [who] trailed me like ants on a sugar spill.”

Toiling in Old-Fangled Ways

The work in that pre-computerized era was all manual. The process had to be gleaned in an auto-didactic manner, rather than by trailing Seniors. Apparently the Railway “maxim” hurled at newbies was “turn the page, learn the work.” Charts for all four coaches were to be inscribed, a task thrust on Vallat because of her pearly handwriting. To issue tickets, she pored over the small print on heavy books, thumbing through nine railway zones, then toting up distances and fares. Coded messages were wired across the railway network via telegrams.

Between writing out charts, filling in hefty registers and scrawling details on tickets, a few errors inevitably crept in. At such times terrorized clerks pleaded with TTEs (ticket collectors) to forgo their berths. If not, enraged customers would escalate their complaints up the hierarchy, resulting in fines or job losses. Walking the length of goods trains to survey incoming and outgoing freight, Sangeetha had her clothes torn on brambles, her limbs stung by insects. She spent hours in rat-infested goods sheds, trading ghost stories with cement-dusted workers.

Delight Amidst the Daily Drill

The job had its highs and mirthful moments: “The issuing of unreserved tickets was an adrenaline rush. We would issue hundreds of tickets in twenty minutes.”

To top it all, there was the sheer diversity of folks she met: “As a ticketing staff, I have seen a gazillion hands – stubby, manicured, burnt, albino, with chipped nails or an extra finger, dark, fair, gnarled, wrinkled, calloused, deformed…” Internal races were won and lost. Vallat was so alert and swift, asking “Ellige, Eshtu and Change Kodree,” whipping through tasks at Olympian speeds, she was known as “Express Lady.” She was even compared with Jayalalitha, who wielded power then. Since their station led to many popular Hindu temples, she encountered VIPs like the physicist, Raja Ramanna, the BJP MP, Sushma Swaraj, and the Kannada matinee idol, Rajkumar.

Lone Lady at the Station

But being the only woman was lonely and Sangeetha yearned for a female companion. When a wizened, old female porter joined after her husband’s demise, she enchanted Vallat with her “ghazals.” Sangeetha was asked to use her voice to record special announcements in three languages for the 50th year of the country’s independence: “Within a few days, my voice became the voice of the town. I felt like Ameen Sayani, the radio announcer of Binaca Geetmala.” To prank her colleagues, she announced their names on loudspeakers when they had stepped out on tea breaks.

Beats Any Travel Book

From the flippant to the serious, from the heartwarming to the harrowing – like suicides on tracks — she’s seen it all through those windows. From a woman who was timorous about weaving a two-wheeler through traffic, she “grew to be unafraid of splattered brains and limbs. But that is how life teaches us and forces us to grow, whether we want to or not.” After reading this book, you will never look at those harried or straight-faced ticket sellers with the same nonchalance. Even if you do, they can write about you, with a flair and verve that might elude the savviest travel writers.

References

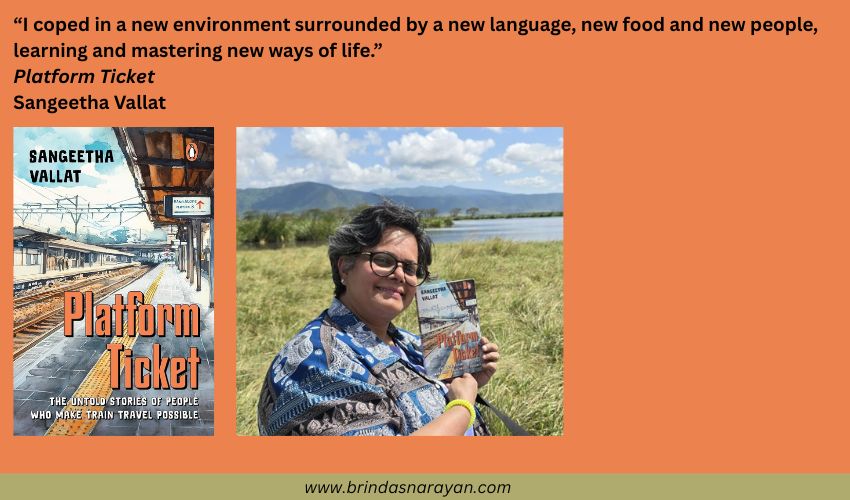

Sangeetha Vallat, Platform Ticket: The Untold Stories of People Who Make Train Travel Possible, Ebury Press, Penguin Random House India, 2025