Lessons that Gandhi Absorbed From His Grandfather and Father

When studying an intensely public figure like Gandhi, one wonders, as one often does with contemporary celebrities or bigwigs, about his behavior in the private sphere. Restless as Mercury offers glimpses into the leader that only those in the closest circles were privy to: namely, his friends and family. Moreover, in typical Gandhi fashion, these incidents are brought to light by Gandhi himself, in a voice that is forthright, expressive and hauntingly melodic.

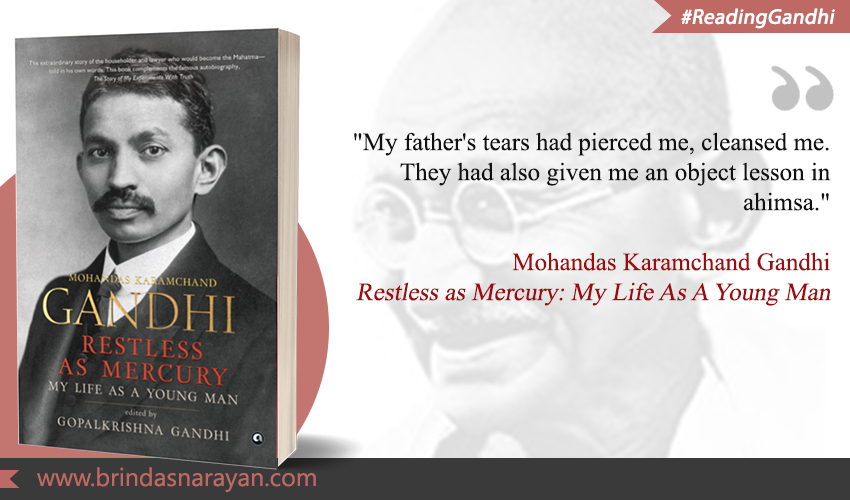

Though Gandhi often dismissed his dexterity with words, relegating himself to the lowest rungs of the writerly ladder, especially in comparison to the more lauded and lyrical Tagore, there is an enticing musicality to his sentences. This book, edited by his erudite grandson, Gopalkrishna Gandhi, is worth diving into, not just to understand the leader’s origins and makeup, but as an evocative guide to those times.

The following are some of my personal takeaways about Gandhi’s grandfather (Ota Bapa) and father (Kaba Gandhi) from the Mahatma’s autobiography:

Gandhi’s Sharp Observations of his Family’s Character Traits

Fiction writers are encouraged to show rather than tell. What’s the difference? “It was a hot day” would be an example of “telling” – of presenting a dry fact. “She couldn’t twist the bottle open. Her hands were clammy” – would be “showing” that it’s a hot day, without saying so. In general, showing works better on TV.

I don’t think Gandhi wrote any fiction, but if he did, I would imagine him belonging to the televisual tribe. Why do I say this? Because when you read his autobiography, you get a sense of sharply observed characters, whose interior traits are divulged by their actions and speech, and not just by dull exposition.

Knowing what Gandhi gleaned from his grandparents and parents throws light on forces that shaped the leader. As the author Robert Fulghum advises parents about their children: “Don’t worry that they never listen to you; worry that they are always watching you.”

Gandhi’s Grandfather or Ota Bapa: Loyal Till the End

Of his grandfather, Uttamchand Harjivan Gandhi or Ota Bapa, he notes his fairmindedness and loyalty. Despite Ota Bapa devoting his life to the Rana, when the ruler died, the Queen dispatched a throng of strongmen to capture his house. The Diwan escaped to a neighboring region, taking refuge with the Nawab of Junagadh. While there, he always salaamed the Nawab only with his left hand. When the Nawab questioned him about why he did so, he responded that his right hand “remains pledged to Porbandar.” He demonstrated such fealty despite being betrayed by the Queen.

Gandhi’s Father or Kaba Gandhi: Staunch and Defiant

Karamchand Gandhi or Kaba Gandhi, was also a Diwan of Porbandar. And later, a Diwan of Rajkot and Vankaner. Like his father, Ota Bapa, Kaba Gandhi was also “uncompromisingly loyal.”

Once, in Kaba Gandhi’s presence, a British Officer spoke disparagingly of the ruler in Rajkot. At once, Kaba Gandhi objected to the remark. The Britisher was infuriated and he commanded the Diwan to apologize. Kaba Gandhi refused to do so, and was held in detention. Even in confinement, when he refused to relent, he was eventually freed.

One immediately senses how Gandhi himself was to mimic this particular action of his father’s, many times over, and with much greater impact.

Kaba Gandhi: Honest and Detached From Money

Moreover, Kaba Gandhi was so incorruptible, that when the Rana himself offered him some land, he refused to accept it. When the ruler asked him to think of his sons, Kaba Gandhi was still adamant in his refusal. Eventually pressured by some members of the family, “he accepted a mere strip of ground four hundred yards long.”

When he died at 63, Kaba Gandhi was left with very little money. Besides being fastidiously honest, he was also immensely charitable. As Gandhi notes: “Money had no fascination for him.”

Ashamed Of His Father’s Carnal Desires

Kaba Gandhi had four wives. The first two died early, leaving a daughter each. The third wife was “incurably ill,” and bore no children.

Apparently, Kaba asked for her permission to marry again, and she sort of taunted him, saying that he could, if someone was willing to marry him. She implied that he was too old to find someone. In response, Kaba said he would find a new wife in 24 hours. And he did.

“With all my reverence for my father, and perhaps because of that reverence, I have not been able to forgive him for this. It showed that to a certain extent, he was given to carnal pleasures, for he was over forty when marrying for the fourth time.”

The fourth wife was the young Putlibai. Mohandas Gandhi was her fourth child.

Kaba Gandhi’s Involvement In the Household

For a man of his times, Kaba Gandhi was progressive in other ways. For instance, he helped with running the household, and even with supposedly feminized tasks like cutting vegetables.

Even during official meetings, he would continue chopping vegetables with a dicer as he spoke to visitors.

Perhaps, Gandhi’s own future espousals of the “dignity of labor” might have stemmed from watching this.

Kaba Gandhi’s Disgust with English Attire

Once when he had to meet with a British Governor at a Darbar, Kaba Gandhi was compelled to wear stockings and “whole boots.” Even as he donned the foreign attire, Gandhi observed the “disgust and torture on his face.”

Much later in his life, Gandhi rejected Western attire with dramatic effect.

They Were Men of Action, Rather Than Being Bookish Sorts

Both Ota Bapa and Kaba Gandhi did not seem academically inclined. Though they held powerful positions, their learning was primarily experiential, rather than bookish. Of his father, Gandhi observes: “Of learning he had something like ‘five books worth’”.

In the last year of his life, based on advice of someone, Kaba Gandhi started reciting shlokas from the Bhagvad Gita. But all along, Gandhi noted, he had Jain, Muslim and Parsi friends, with whom he engaged in deep discussions.

Gandhi’s Remorse and A Confession to his Father

During his adolescence, Gandhi started smoking beedis with a relative, even stealing “coppers” from servants to fund his habit.

But beyond this, another incident fostered greater remorse. His meat-eating brother had run up a debt. To pay this, Gandhi suggested they remove some gold from a wristlet worn by his brother and sell it. They did so, to settle the debt.

Gandhi was afraid of verbally confessing this to his father. Instead, he wrote out his confession on a slip of paper and handed it to Kaba Gandhi. At that point, the older Gandhi was ill and bedridden. He read his son’s letter and with tears rolling down his cheeks, he tore it up. In other words, he did not remonstrate or rebuke him. He absorbed Gandhi’s guilt and hurt him acutely by not shouting.

Of this scene, Gandhi says: “Rama’s arrow heals even as it hurts.”

Watching his father being hurt by his misdeed was more piercing to Gandhi than his anger would have been. “My father’s tears had pierced me, cleansed me. They had also given me an object lesson in ahimsa.”

This incident might have seeded his lifelong belief in the power of nonviolence. On its capacity to inflict hurt on the other, by deliberately withholding one’s response.

References

Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi, Restless As Mercury: My Life As A Young Man, Aleph Book Company, Delhi, 2021 (Edited by Gopalkrishna Gandhi)