Extraordinary Undercurrents in Ordinary Bengaluru Lives

We live in an age in which there seems to be a surfeit of extraordinary people. Superstar founders, sportspersons, writers, singers and stand-up comedians. Even failures in various fields have acquired an aura of extraordinariness. In such times, encounters with the opposite – with folks who are self-consciously ordinary feels both startling and even strangely spectacular.

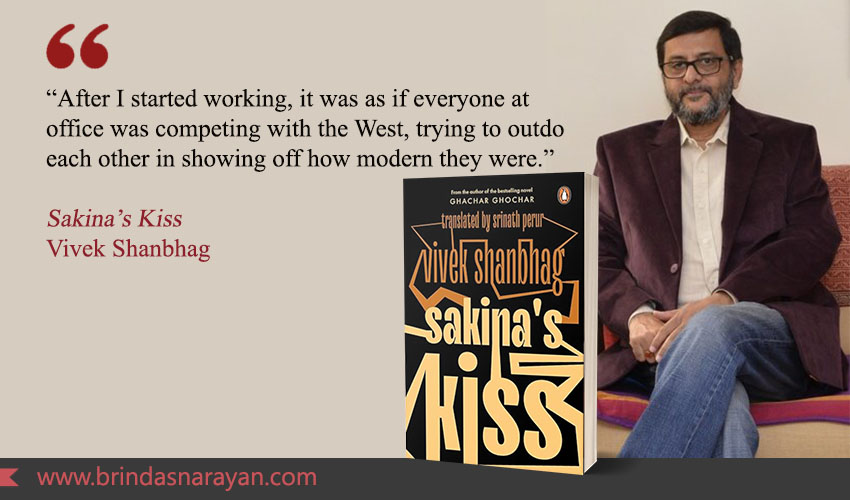

Vivek Shanbhag, like Chekov and Kafka, recognizes that the averages or mediocres can be mined for social or psychological insights, as the outliers rarely can. It’s in their seemingly humdrum everydays that one discovers the interplay of complex forces: globalization, the criminalization of the political class, the affable violence of caste and gender relations.

Of course, Shanbhag’s intent might be more straightforward: to tell a page-turning story. But as a sharply observant literary writer, who is carefully attuned to subtle changes in his character’s environs, his novels can be considered an authentic guide to a city that no longer knows itself. Where flux is the only constant, and where even the middling folks sense that disorder always lurks at the edges.

When the rather surly protagonist of Sakina’s Kiss searches for something trivial – a carpenter’s visiting card, in this case – his poking about mimics the doom scrolling of digital natives. He falls into a rabbit-hole of remembrances and what-could-have-beens, alighting on one-time quotes scribbled into notebooks, into possible and past selves. He too, like others in his generation, who maybe overawed and unnerved by a changing terrain, is aware of an ongoing chipping away of the only thing that once felt stable: himself.

In All that is Solid Melts into Air, Marshall Berman had dwelt on the disorienting tugs of modernity: “To be modern is to find ourselves in an environment that promises us adventure, power, joy, growth, transformation of ourselves and the world — and, at the same time, that threatens to destroy everything we have, everything we know, everything we are.” It’s a kind of vanishing that Venkataramana is woefully aware of.

To begin with, there’s the diminishment of his name. The extravagant mustache-twirling Venkataramana, who might have been a charismatic force in his village, finds the “ahs” in the middle and end carelessly pruned by North Indian peers at his engineering college. Just like that Venkataramana becomes Venkatraman. And we can’t be blind to power relations here. It’s the North Indian tongues that do not care to flicker across South Indian extensions – not because they can’t, but because they don’t need to.

Later, at impatient, scurrying offices, Venkatraman is shortened to Venkat. The protagonist imagines that if he had traveled to the U.S., he would have been further truncated: into a Disneyesque Venky.

At midlife, it’s not the name changes that bother him as much as his own acquiescence: “Perhaps the transformation of my name says something about the path I have travelled, and my easy acceptance of it something about the firmness of my convictions.” It’s in such seemingly superfluous details that Shanbhag packs in so much: the shame at being outdated and old, the thrill of new aspirations, the flattening of regional flourishes into a crisp and clipped homogeneity.

Venkat has a steady career. He’s gradually climbed the ranks at various companies, but never reached far enough to possess a view from the top. He wonders what life would look like from those high perches. His wife, Viji, with an MSc in Maths also works for an IT company.

Though their first meeting was “arranged”, thereafter they met a few times before getting engaged. Venkat liked to think of himself as a “liberal” – as someone who wasn’t mired in caste or rituals. That, of course, is a conviction that’s going to get tested, as the novel progresses.

At their honeymoon, they both discover a shared interest: in self-help books. An aspect that they are both embarrassed to reveal and discover: “Those who read such books will understand the self-doubt and shame that accompany being seen reading one of them.” Ironically enough, they had each carried a copy of “Living in Harmony”. But they also realize the fallacy of a “self” that exists outside the influence of externalities. For if they are indeed, from thereon, living in harmony, should they credit the author or themselves? And, is everything they say and do coming from a “true” inner self, or from some smooth-talking, glib guru?

Soon enough, differences start emerging. Viji is more flippant about these books, while to Venkat, they are veritable bibles. Or rather indispensable guides to urbane workplaces, to city-bred and Westernized colleagues. But the self-help books can hardly offer pointers to the sudden twists and turns that life and their spirited and combative daughter will subject them to.

The novel, which reads like a thriller, starts with an unexpected knock on the door and the entry of two strangers. Two boys who claim to be friends of Rekha, their college-going daughter. The somewhat naïve, tax-paying and salaried couple are hurtled into a more surreal realm: of gang wars, and gun-toting reporters. Like in Ghachar Ghochar, Shanbhag quickly introduces a sense of foreboding. Where it feels like no one is really shielded, because darker elements are only a door knock away.

Moving between the village and the city, Shanbhag sketches family tussles, intergenerational conflicts, betrayals over property and the ongoing reduction of women into objects. All this with a touch of humor and empathy for Venkat, who turns out to be an unreliable narrator. And I must add here that Shanbhag is particularly deft at creating shifty characters whose vacillations are reminiscent of the dilemmas faced by Raskolnikov in Crime and Punishment. And fortunately for our digitally-addled age, he does it in far fewer, tautly-written pages.

While I read the English version skillfully translated by Srinath Perur, I can imagine how the Kannada original would offer a different set of riches: the interplay of dialects, the frisson of class, caste and gender beaded into words. Many inhabitants of the nation’s IT city contend with complications. But one of its biggest gifts maybe writers like Shanbhag, who can turn those troubles into something beyond the ordinary.

References

Vivek Shanbhag, Sakina’s Kiss (translated by Srinath Perur), Vintage, Penguin Random House India, 2023