Lessons from the Self: Flaunting my Silvers – Part 1

I’m 53. Strange that such a straightforward fact, the only data point perhaps, over which I can claim to have some certainty, should feel, in the contemporary era like a guilt-ridden admission. As if one ought to be defensive for having inhabited the planet for five whole decades, bearing witness not only to the tidal shifts and miniscule flutters in our surroundings, but also in the self. As a writer, I am naturally inclined and perhaps even obligated to stay introspective and curious. And honestly, though people and places continue to fascinate me, I am equally intrigued by an elusive, shifty and hard-to-pin-down entity called “me”.

That creature and especially the burgeoning whiteness on its top has received more attention since the lockdown. Though given how the last year has ushered a Global Pause, a societal and cultural reset of sorts, it seems absurd that I would dwell on something as frivolous as my hair color. Still, if a literary great like Marcel Proust could spend so many pages on a madeleine (a type of sponge cake) dipped in tea in The Remembrance of Things Past, surely, those of us occupying the lowest rungs of the writerly ladder can accord a few paragraphs to hair.

To begin with, this was a pre-Covid decision. To stop dyeing and to start living. I even made the announcement to a gathering of cheering relatives and cousins, some of whom had already trotted down the path, and who championed the sheer practical benefits. For one thing, the relief from the monthly or biweekly rituals, that had us in thrall to salon workers or to sloppier Do-It-Yourself kits rated by fervent or flustered Amazon reviewers. One cousin said she could travel internationally without worrying about finding a place to get her hair done. Another said she was receiving more compliments now that she was sporting an “Au Naturel” look.

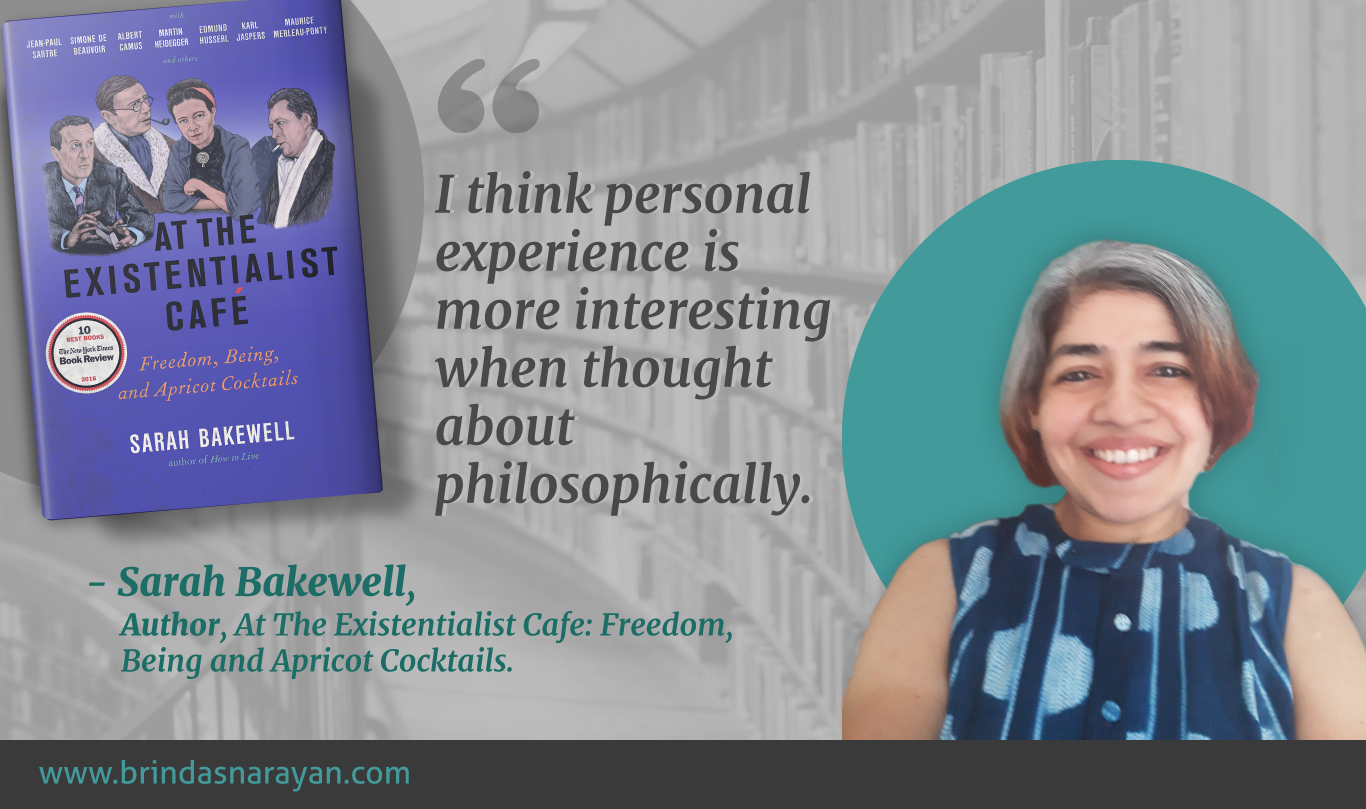

But that was only the announcement. The decision had been made earlier, in the midst of reading At the Existentialist Café, a book by Sarah Bakewell, that recreates the lives and intense discussions that underpinned the Existentialist movement, led by colorful thinkers like Jean Paul Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir. In the book, a captivating read even for those of us with no formal training in philosophy, Bakewell transports us to Paris in the early 1930s, a time of great cultural and social ferment in the French capital. And though, I was reading this inside my Bengaluru kitchen, sipping gingery tea, I was parachuted by the author’s vivid recounting, into a wildly different time and place.

From At the Existentialist Café: Sartre and Beauvoir Discover New Ways of Being

To the rue du Montparnasse in Paris, in 1932, where three young philosophers sip apricot cocktails at the Bec-de-Gaz bar. The philosophers are astonishingly young. Simone de Beauvoir is only 25, while her boyfriend, Jean Paul Sartre, is 27. They are chatting with Beauvoir’s school friend, Raymond Aron. The two seem completely engrossed by what Aron is telling them. Since all three are convening after a longish spell, they are introducing each other to new discoveries. Aron is talking about a new word he encountered at Berlin – “phenomenology.” As Bakewell puts it, it’s a “word so long, yet elegantly balanced.” The idea, apparently, was less complex than it sounded. German philosophers who were advocating this idea felt that people should, for the time being at least, abandon the old “theories” and focus on the “things” of the world. Instead of turning over theory after theory inside their heads, they should attend to passing moments as they occurred, or to the concrete “appearance” of stuff around them.

The leader of the movement, a man called Edmund Husserl suggested a new slogan for the approach: “To the things themselves.” Martin Heidegger, also a phenomenologist, said besides questioning the appearance of things, and their reality or apparent reality, they also needed to ponder the essence of Being. What does it mean, for any living creature, to exist? In other words, what did it mean for the apricot cocktail to be an apricot cocktail?

Sartre and Beauvoir, who had been looking for a new approach to “knowledge” felt completely shaken and excited by this new idea. Aron suggested that Sartre move to Berlin for a summer and study the subject further, from German sources. Sartre had been looking for a change. After all, he was bored with his life. Besides, his genius wasn’t flowering in the manner he had expected it to. He felt he needed adventures to sow the spark. So, the Berlin invitation felt opportune. After a few months there, he returned to France, and fleshed out his learnings, infused with his own “literary sensibility.” He also made the idea more internationally widespread and gave it a new term: “modern existentialism.”

In Sartre’s work, like in any novelist’s take on a serious subject, he injected the topic with the forms and feelings of life: “the thrill of a boxing match, a film, a jazz song, a glimpse of two strangers meeting under a street lamp.” More than anything else, he wanted to explore the notion of not just what it meant to be human, but to be “free.” “Freedom, for him, lay at the heart of all human experience, and this set humans apart from all other kinds of object,” writes Bakewell. Though all human beings are subject to the circumstances of their birth, and upbringing, and cultures and so on, they also possess an ability to escape these aspects. In Sartre’s own words, “none of this adds up to a complete blueprint for producing me.”

He summarized his philosophy in three words: “Existence precedes essence.” Though one might be labelled “X” or “Y” – a wife, or a CEO, or a slave, or a student – one can evade all these imposed identities, by taking specific, deliberate actions. As Bakewell observes, “I create myself constantly through action, and this is so fundamental to my human condition that, for Sartre, it is the human condition, from the moment of first consciousness to the moment when death wipes it out. I am my own freedom: no more, no less.”

Soon after broadcasting his ideas in various forms – essays, radio talks – Sartre very quickly turned into a celebrity. Beauvoir, who had her own take on existentialism also produced stories, essays and other works, and often the two of them were both seated in the middle of fawning listeners, at various events, in high chairs, like the “king and queen of existentialism.” Perhaps, of the two, Sartre was the one who was the bigger draw. At one particular event in Paris, where the people actually fainted because of the crowds (and lack of air inside the room), the TIME magazine bore the headline: “Philosopher Sartre. Women Swooned.”

At the Paris event, Sartre’s talk dwelt on the kind of conundrums we human beings are faced with all the time. For instance, he spoke of a French student, who was taking care of his aged mother, when the Nazis had killed his younger brother. The student was torn between two contending, equally well-intentioned desires: on the one hand, he wanted to stay with his widowed mother, to ensure her safety and well-being. On the other hand, he wanted to fight the Nazis and avenge his brother’s death. But in fighting a nationalist cause, would he betray his family? Should he save many lives or one? The problem for the student was that no philosopher or any other academic could give him an answer that would justify his decision. Sartre said that such decisions and such gnawing anxieties – should I pursue a career, and hence leave my child to a caretaker? – are an inevitable burden of “freedom” that human beings experience. As Bakewell puts it, “Starting from where you are now, you choose. And in choosing, you also choose who you will be.”

In a later interview, Sartre said: “There is no traced-out path to lead man to salvation; he must constantly invent his own path. But, to invent it, he is free, responsible, without excuse, and every hope lies within him.”

Naturally, religious authorities were among the first to fear Sartre and Beauvoir. They put Sartre’s immense Being and Nothingness, and Beauvoir’s The Second Sex on a list of banned books. But the Marxists disliked him too. Because if Sartre thought of humans as “free agents,” they felt that people would not submit into being obedient participants in a revolution. The idea that seemed to appeal to Sartre’s listeners, but not to Authority figures in the Left or Right-wings, was the sense of each person being an agent of his or her own destiny. Naturally, the people who really took to it were younger – after all, if you could be free, you could be free to sleep at any hour, to party as long as you wanted at jazz bars and clubs, to defy one’s parents and teachers.

Choosing to Flaunt my Silvers

I had reached roughly that point in Bakewell’s book, when I suddenly realized – even at 53 – that there was a “freedom” that I could seize right away, and not even one that required any action on my part. And though no one was going to notice this inaction, apart from a small coterie of neighbors, friends and relatives, it was going to be a statement of sorts. Because as a writer, I’m acutely conscious that everything we do (or don’t) as human beings carries semantic weight. Moreover, as someone inhabiting a profession that usually bucks productivity measures, it felt hugely liberating to stop an activity that imposed itself with a rhythmic persistence. And was moreover determined by factors over which one seems to have little control: the growth of new white hairs, or the rate at which erstwhile black strands shed their melanin.

While I only had ghostly versions of Sartre and Beauvoir as witnesses, I could hear them champion my latest resolve: to flaunt my silvers. This is the first of a series of articles on consciously inhabiting a new cultural and psychological geography, a grey-haired self. My new hair, weirdly enough, glaringly clocks the march of time, since the whites on top signify the present, while the hennaed reds at the bottom hearken to the past. Why absurdly red, given that my youthful strands were black? I will dwell on that in a future post.

References

Bakewell, Sarah, At the Existentialist Café: Freedom, Being and Apricot Cocktails, Chatto & Windus (Vintage), Penguin Random House, London, 2016

Very well written… I set out to flaunt my silvers during the lockdown. But once it ended, the lure of a darker mane and comments by family, pulled me back to their hennaed version. But there is hope still…. One day soon I will achieve this freedom:). There are more pressing things to be free of till then!!