Exploring Baghdadi Jewish Heritage

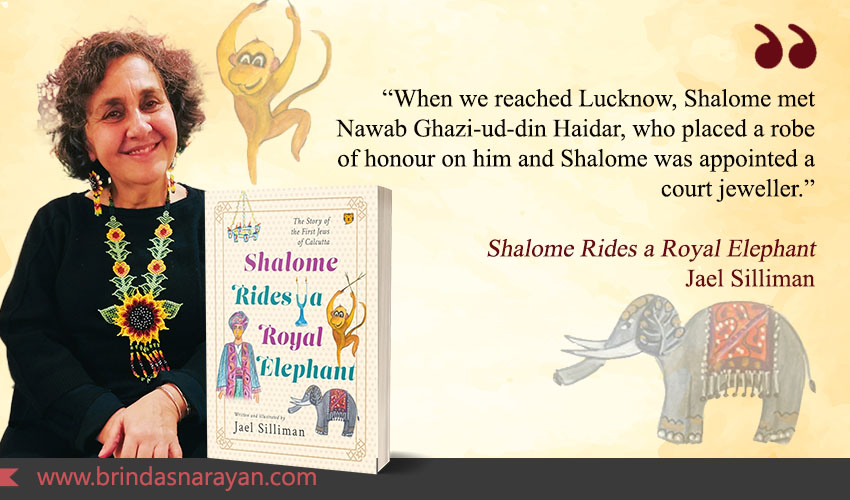

Plumbing into her own family’s ancestral past, Jael Silliman revives snippets of the rich and little-known history of Baghdadi Jews in Shalome Rides a Royal Elephant. Though targeted at young readers, and narrated by a sprightly, impish monkey, “Chanchal”, the pages can be munched through by readers of all ages as one might with crackling, finger-licking wafers. It’s a humorous, moving, and illuminating tale of Jewish life and of a multicultural city, where many groups and religions have coexisted peacefully for centuries.

Jewish Roots in Calcutta

Shalome Obadiah ha Cohen was the first Baghdadi Jewish settler in Calcutta. Baghdadi Jews are one of the three distinct and culturally variegated communities that make up the Jewish diaspora in India. The others being, the Cochin Jews and Bene Israel (with the latter largely spread across the Konkan coast, including in Mumbai).

The original Calcutta settler, happened to be Silliman’s great, great, great, great, great – whew! Got that right – grandfather. He was also a painstaking diarist, leaving behind an account of his itinerant, bustling life.

Written in Arabic, in the Hebrew script, the diary is a testament to the one-time syncretic relations between Jews and Muslims. Beyond that, it’s also proof of how different faiths were always woven into the makeup of India, and even if most Jews have since left Calcutta, traces of the thriving community echo inside the stately stillness of three synagogues, a couple of prayer halls and schools.

Building a Family

Though broadly classified as “Baghdadi”, these Jewish immigrants arrived from many parts of the Middle East. Shalome himself had set out from Aleppo, Syria to land at Surat, in 1792. Rich, charismatic and quick to spark off a business, he was perhaps eyed by local Jewish mothers as Darcy might have been in Pride and Prejudice. Snatched up he was, soon enough, by Najima’s family, who shepherded her to their first arranged meeting, dressed as a young boy. Najima was so attractive, her family couldn’t risk other men laying their sights on her.

While Najima, like many women of that era, stayed yoked to domestic tasks – baking honeyed baklava and birthing kids (nine in all) – Shalome travelled to other regions, zigzagging between cities and ports that traded with each other. Like to Basra, in Iraq. Recognizing that Calcutta, as the seat of British power then, was a more opportune destination, he moved out of Surat. And headed to the riverine port, by boat down the River Ganges.

Silks, Faith and Charity

Najima and the girls joined him in a few months while Shalome drew in other Jews from Aleppo and Cochin. Religious and fastidious about Jewish rituals, he constructed a prayer hall at home and prayed several times a day, with a leather box strapped to his head or a brimless cap. Life, prayer and work were thus stitched into a seamless blur, with practices that harkened to the past occasionally punctuated by concerns about the future. Displaying a foresight that might evade even contemporary life planners, he bought a large plot of land for his family’s burial.

Trading in silks, textiles and indigo, he was conscious too of giving to charity. As Shalome tells the delightful narrator: “Chanchal, one must never take without giving. And it is always better to give than to receive.”

Jewels, Royalty and Wisdom

Invited to Lucknow by the Nawab, Shalome assumed the mantle of a “court jeweler”. Winning the king’s trust with his wisdom, he became a Vazir or advisor to the king. He even rode a royal elephant with the Lucknowi ruler and returned to Calcutta in grandeur: escorted by palanquins, soldiers and servants.

In 1822, Shalome visited Maharaja Ranjit Singh in Punjab, the owner of the famous and rather controversial “Kohinoor” diamond. By now, Shalome was 65-years-old. He wanted to spend less time on his business, which he had mostly handed over to his son-in-law, Moses Dwek, while he attended to internal forays. Through writing and praying. In 1836, Shalome passed away. Because of him, many other Jews moved to Calcutta to settle.

His poems are instructive even for contemporary readers:

“Now turn to me and listen (to) what I say.

Make haste, repent, give alms this very day.

Do not delay and leave it till tomorrow.

The day is short – and the time you cannot borrow.”

Bonus: A Conversation With Jael Silliman

Q: What inspired you to embark on this project?

Silliman: I have never written a children’s book, so this was a leap for me. The diary of my ancestor charts the beginning of the history of our community. The document was actually bought by a collection and was housed in Jerusalem in microfiche. My brother and his son were very interested in genealogy and they dug it out and had it translated. The original is in Judeo Arabic – which means it’s Arabic written in the Hebrew script. Since it was such a colourful story, I thought it lent itself very well to a children’s book.

Q: The book is also beautifully illustrated with watercolor paintings. Can you tell us about the creative process that led to this?

Silliman: I’ve been painting for the last six years, and a lot of people like my work. I’ve done about 400 paintings since then and have sold 250. So after I’d written the book, I just jumped into it. And the illustrations just seemed to emerge very quickly. It took me about half an hour or 45 minutes to do each one, and that’s how the book came together.

Q: What went into researching this project?

Silliman: My brother had some of the diary details. He’d gone through it very meticulously because he got it translated. So I sent the manuscript to him for all the corrections. My sister was very helpful too. She’s a literature major and also just a fun person. She’s a chef, actually, in Israel. She gave me a lot of tips, especially to make it more appealing to children.

Q. How did you decide to narrate this from the point-of-view of a monkey?

Silliman: I think subconsciously I had a picture of my dad with a monkey. It’s a children’s tale, I wanted it told by an animal because that would make it more animated, more fun. I thought maybe a horse, because Shalome travels by horse and carriage. Then maybe a bird. But with a bird, you don’t have that kind of communication and naughtiness. My brother said, how about a monkey and it clicked. I love the idea of a monkey because they’re so much like us, and they’re naughty and mischievous and nimble. They’re also intrinsically Indian.

Q: What are you working on next?

Silliman: I’m working on a nonfiction book. On the history, life and politics of the Jewish community in Calcutta from 1796 to the present.

References Jael Silliman (author and illustrator), Shalome Rides a Royal Elephant: The Story of the First Jews of Calcutta, Talking Cub (Speaking Tiger Books), 2023

It was indeed so enriching going through the narrative.

Extremely inspiring person is Jael Silimon . Blessed to meet her in one of my painting workshop.