Translating Worlds: Srinath Perur’s Journey from Bytes to Books

Uncles, Aunties and Banter on Buses

In If It’s Monday It Must Be Madurai, Srinath Perur subverts the common trope of a travel writer. Instead of traveling alone, or to rarely explored, offbeat places, he does what most writers might deride or shun. He deliberately rides out on buses, trains, boats and flights with gossipy, aggravating, inquisitive Uncles, Aunties and other Wodehousian life forms – some foreigners and many desis. Moreover, he ventures on these kitschy tourist paths not so much to study places, but to watch people. His co-passengers are the subject of his travel book, which gives you insights not only into the places trodden, but about who travels and why.

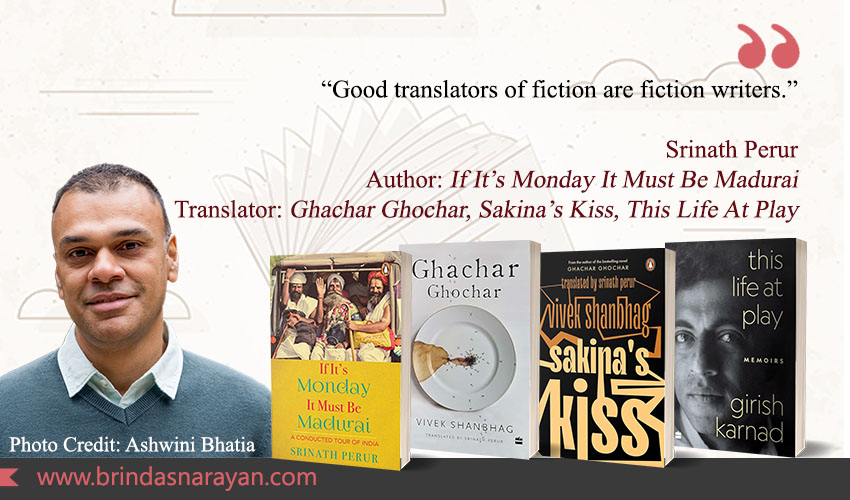

Penned with a slightly askance view of the world, the book evokes a response that writers yearn for but seldom achieve: side-splitting laughter. Besides his narrative nonfiction work, I’ve also read his nimble, elegant translations of Vivek Shanbhag’s works: Ghachar Ghochar and Sakina’s Kiss. When we settle down to converse at the leafy NGMA café in Bengaluru, I’m apprehensive about not being clever enough. After all, Perur is not just deft in English, but also in Kannada. When he recounts his academic journey – with a trademark casualness or flippancy – I’m further startled by this: he holds a Doctorate in Computer Science.

Monkeying With Words

Let’s backtrack. He grew up in Bangalore, attending Poornaprajna, a “Hindu convent” that Perur notes, boasted of a 100% Pass. He has fond memories of his Kumara Park home, of monkeys squatting on the refrigerator, chomping fruits. Of sparrows flying hither-thither, a species that has unfortunately dwindled since then. He also cycled everywhere, something that is harder to do now. And played cricket on the street, an activity that’s equally fraught, given the density of city traffic.

He had a marked proclivity for words, even at an early age. When in Kindergarten, a teacher handed out picture books with a stern: “Don’t just look at the picture, read the text also,” Srinath had shut his book before any of the others. She then chided him: “I asked you to read, not just look at the picture.” He said he had read everything. The teacher did not believe him. She asked him to narrate the story. Which he did. “Without my being aware of it, I had an aptitude for words.”

Pedaling Through Pages

At school, librarians were among his favorite staff members. One of them even used to bring books from home, if they didn’t have particular titles. He recalls a shelf filled with Wodehouse books. He devoured all. He was enchanted that words could elicit laughter. He accompanied his mother, who worked at ISRO, to the British Council Library.

Besides school libraries, he was enrolled at proximal circulating libraries, walking across to check out books “indiscriminately” and pore through them. Thrilling page-turners by Frederick Forsythe and Robin Cook. On vacations, he’d borrow a book in the evening, read till 3 am, and return it the next day. He recalls how that was a different time, when you had to pick books without knowing much about their contents. This process of running his eye across shelved spines led Perur to astonishing and provocative works. Like to Graham Greene, even when he was too young to grapple, like the English writer did, with moral dilemmas.

As he traversed high school, he started getting a sense that words were a means to tackle the mess of human life. There was a charge to reading like there was to little else. He stumbled on R.K Narayan. And suddenly had the feeling that his own stories were legitimate, that his ordinary Indian experiences – those fruit-thieving monkeys, those brown-backed sparrows – were riveting. That one need not grow up in London or New York to be a writer. Later, he heard that other writers – like Perumal Murugan – also felt their own experiences being validated by Narayan.

From Books to Bytes

Since both his parents were engineers, he gravitated, as a kid with academic smarts, towards the inevitable pathways of middle-class families: engineering and medicine. After his PUC at MES College, he was admitted to both Engineering and Medical colleges. He chose to pursue Computer Science at REC Warangal.

Despite flourishing in the system, Srinath recalls being indifferent to stuff dinned at school. He felt that he had excelled in that crack-the-exam, utilitarian manner, without savoring underlying concepts. Later, as a college student, he was to appreciate linkages between mathematics and language. With proper teaching geared towards unfolding basic laws, he felt one could “unlock the beauty of both subjects.”

Warangal was memorable in other ways, not all salubrious. Located in a region where the Naxalite movement had once taken root, the college was influenced by its tumultuous surroundings. The ragging was severe. It wasn’t just verbal jousting, or clever pranks. It involved grueling, physical beatings. One university senior would lock up seven or eight juniors in a room, then slap each one. As someone who had grown up in a relatively shielded environment, witnessing such brutality was disorienting. It was also a lesson for Srinath, as a writer, in power dynamics. Which prevail across broader societal structures, based on factors such as gender, caste, or wealth.

But the courses were enjoyable, as he delved into various programming languages and learned to build compilers. His pattern-detector brain also made connections with human languages. That kindergartner’s enchantment with sounds and words had never faded. He still chews on relationships between everyday languages and coding while engaging in translations.

Slaying Boredom With A Blog

At the end of his four-year degree, he secured a position at a now-defunct IT company in Bangalore called Mascot Systems. Involved in IT software maintenance, he quickly grew bored with his role. Contemplating next steps, he concluded that he might be more stimulated by sophisticated work. To climb the technology ladder, he figured he should study more. He quit his job to prepare for the GATE exam. And enrolled in a Master’s program at IIT Bombay. During his studies, he started sensing that his true talents lay elsewhere.

He started a blog, deviating from technical topics to focus on writing itself. Utilizing the platform, LiveJournal, he found an audience appreciative of his work. Writing, he felt, could serve a dual role: as an outlet for self-expression and as a means of personal fulfillment.

On completing his Master’s, he decided to persist with his academic journey by signing up for a PhD. Staying on at IIT Bombay seemed like a route to delay his workforce entry and to explore other interests. He also harbored patriotic aspirations. He thought he could use his education to better the nation, even as he sought personal growth through travel and writing. “There’s this idea that patriotism is the last refuge of the scoundrel. It’s also the last refuge of the confused,” he chuckles.

Shrugging Off Lab Coats

Armed with a doctorate, he joined Motorola Research Labs in Bangalore to work on a project to bring connectivity to rural India, a job that aligned with his inner mission: of serving the nation, in some way. But his yearning to write lingered, leading him to contemplate quitting to pursue writing. Full-time. Even if he needed to forego the steady whoosh of a “Salary Received” message.

The inclination intensified after winning a prize in a Deccan Herald short story contest with a submission that caught the attention of the writer Vijay Nambisan, one of the judges. Meeting Nambisan, himself an IIT fourth year dropout and poet, left a profound impression on Srinath. He found himself drawn to the idea of a writerly life, cherishing time spent in the company of such a fine literary mind. Engaging in lengthy conversations, punctuated by Nambisan reciting snatches of his poetry, sparked something that Perur’s college lectures hadn’t. But how would he embark on such a career?

Chasing India’s Middle

In the meanwhile, another question had been plaguing him during his doctoral studies: where was India’s geographical center? Not finding this easily, he became rather obsessed with traveling towards it, maybe pinning it down for all eternity. He sought assistance from the earth sciences department at IIT Bombay during a visit for his PhD defense. And obtained coordinates for India’s supposed center, a task made challenging by the absence of GPS technology in phones at the time.

He then set forth towards the geographical center in Madhya Pradesh. While journeying there, he realized the concept of a fixed center was flawed. His penned his reflections in an essay, arguing that the nation’s center was a fluid and subjective notion, a point always in flux, affected by shifting shorelines, political boundaries and territorial disputes: “Borders change every day. They change with tides. Or when you have a tsunami. The map changes by itself. And do we consider islands that are territorially part of the nation, but not geographically contiguous?”

The quest might have stayed incomplete, but his essay was done. Submitting it to various publications, he received rejections. Till Kai Friese, then editor of Outlook Traveler evinced interest. Featuring a shorter version in print, the magazine published the entire article online. Even today, Perur feels a surge of gratitude towards Friese, for considering the submission of an unknown writer. Friese also started assigning him travel pieces. By then the Motorola research project had been terminated, so the timing was fortuitous.

Trippy Tales: Laughs on Wheels

One of his assignments from Outlook Traveler involved a bus tour of Tamil Nadu. When Kamini Mahadevan, a Penguin editor residing in Chennai read the piece, she reached out with a book idea. Perur suggested theme-based group tours. After all, people with their foibles amplified inside claustrophobic buses or trains, could be fodder for hilarious accounts.

Armed with a book contract and a modest advance, Srinath embarked on various travels. Ensuring that he always had just enough to fund his travels and living expenses, Perur completed the book over three years. Since then, the book’s ongoing reprints and continued sales still earn a modest royalty for the author.

Lost in Translation: Reconnecting with Kannada

After this, Srinath experienced what he terms “a crisis of authenticity” about reading and writing solely in English. Feeling disconnected from his roots, he sought to rekindle his relationship with Kannada. He attended Ninasam, a cultural festival hosted by a theatre institute in Heggodu.

At the festival, he connected with Vivek Shanbhag, who was already prominent in Kannada literary circles. Having read some of Srinath’s short fiction, Shanbhag asked him if he would consider translating a novella. Srinath hesitated. For one thing, his reading speed in Kannada was slow. Besides, he had never done something like this. Shanbhag’s encouragement persuaded him to accept the project.

Of the process, Srinath recalls: “I took a long time to read it. In fact, I used to joke that I read Kannada so slowly that I might as well type it out in English on the side and translate it.” As he immersed himself in the work, his reading speed in Kannada gradually improved.

Ghachar Ghochar was a triumph. It brought well-deserved international attention to Shanbhag’s literary talent (who was compared variously to Chekov, R.K. Narayan and many other legendary writers). The book featured in The New York Times, The Guardian, The Globe and Mail to name only a few. It was shortlisted for The Los Angeles Times Book Prize in 2018.

Of Srinath’s translation, Preti Taneja of the New Statesman wrote: “Perur’s translation captures the heartbreaking achievement of Shanbhag’s writing: to present, in a line or two, a body and mind coming of age in a society that casts violence as tenderness, ownership as love.”

Exploring Words and Worlds

Discovering a penchant for translation prompted him to embark on translating two more works by Shanbhag. He also started assisting Girish Karnad with translating his autobiography, This Life at Play. Though Karnad initially intended to work on it himself, his illness prevented him from doing so. After Karnad’s death, Srinath completed the translation, which was published posthumously.

When it comes to translation, Perur believes in thoroughly absorbing the original text before rendering it into English. The act of internalization allows him to convey the essence of the original work in a manner that feels natural and authentic in English, employing techniques akin to fiction writing to ensure coherence with the source material. “I think of translation as writing. It’s a form of writing to me, except you’re constrained by the original text.” Though he had never been trained in writing, as he puts it: “What better training is there for a writer than reading?”

Beyond translations, he also writes on various topics. While he admits to being peripherally connected to technology, he engages in Science writing, covering some of the latest research on trendy topics. Some years ago, he did an article centered around the impact of Mohanswamy, a collection of short stories by Vasudhendra. Intrigued by how the book had bolstered gay men in Karnataka, especially those living in small towns and villages, Perur visited those places, to meet readers in their settings.

He divides his time between Bangalore and Dharamsala, even as he translates a third Shanbhag book. And contemplates writing another book, maybe on the prehistory of India. Or on anything else his imagination and whimsy leads to.

References

Srinath Perur, If It’s Monday It Must Be Madurai: A Conducted Tour of India, Penguin Random House India, 2013

Vivek Shanbhag, Srinath Perur (Translator), Sakina’s Kiss, Penguin Random House India, 2023

Vivek Shanbhag, Srinath Perur (Translator), Ghachar Ghochar, Harper Perennial, Harper Collins India, 2015

Girish Karnad, Srinath Perur (Translator), This Life At Play, Fourth Estate, 2021

Hi Brinda, landed on your blog via linkedin. Lovely piece! you had me at ‘Uncles, Aunties and Banter on Buses’ It sounds like such a great title for a novel 🙂

A lovely profile, in equally elegant words