Exploring the Power of Conversation

An Academic Who Relishes Conversations

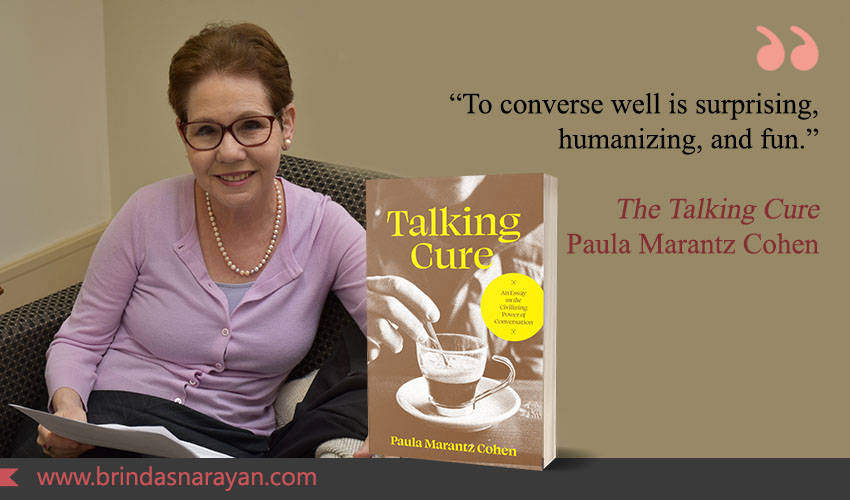

Paula Marantz Cohen is currently a Professor of English and the Dean of a college at Drexel University. Despite being deeply erudite, sharp and incisive in her writing, she claims that one of her favorite activities is a more convivial and perhaps rather ordinary one. She enjoys talking to people. Not necessarily only to intellectuals, or to fellow professors and students, but to many others. She realizes, after all, as a humanist, that original insights can come from anywhere. From a plumber who hasn’t been to school at all, or from a street sweeper who has experienced her city in singular ways.

Learning to Converse at College Seminars

Since most college degrees attempt to lift our reading, writing, critical reasoning and number juggling skills, there is scant regard paid to what is perhaps an eroding human quality: to conduct a civil conversation with anyone. Especially with people who may not think like you at all.

Cohen finds as a professor, that she enjoys conducting seminar classes, where students are drawn into conversations as active participants. Summoning memories of her own student days, she senses how seminars require the instructor to be particularly deft at conducting them well. To not make students anxious about sounding clever or even about speaking up n number of times. In the best discussions, professors detour into compelling tangents, allowing students to guide them into unexpected directions. And thus expand their own understanding of the material.

Student takeaways are not limited to academic insights. They learn to converse better, to tolerate different points of view, to bounce their own unformed thoughts against a collective brain, to verbally articulate their ideas – all necessary skills for any future occupation.

Talking as Therapy

It was Sigmund Freud, the founder of psychoanalysis, who suggested that many folks had repressed desires and concerns that resulted in physical illnesses. The term “talking cure” was coined by Anna O – a patient of Freud’s colleague, Joseph Breuer. Freud himself loved talking. He was outgoing, he loved discussing ideas. He was also an expressive writer, who wrote in a conversational style that tugged readers in. But he could also be arrogant and opinionated, so perhaps he wasn’t the best person to converse with.

Paula does not suggest that we talk only as patients and therapists. She likes the idea of “transference” – the “infatuation” a patient might develop with a therapist, who can be a stand-in for a parent. She says we can experience this when we talk with affection to anyone – a friend, a stranger, or even to a group of students. Unlike sex, which ends or culminates in orgasm, “friendships are never over after a good conversation; they are sustained by it.”

Beyond psychoanalytic sessions, talk can be therapeutic in other settings. Paula dwells on Alcoholics Anonymous and the manner in which their group sessions help members overcome addictions. The bar conversation has been now substituted by a healthier version, where the burden of addiction is handed over to a higher force – which can be called “God” or even just the collective watchfulness and support of the group.

Talking to People with Different Views

It’s often fruitful to talk to people who might disagree with us. Cohen, herself, who came from a left-leaning Jewish family forged a strong bond with an academic colleague who was a staunch political conservative from Kansas. We ought to see people as nuanced human beings. It’s another reason to read literature. “Literary characters, when well drawn, are neither saints nor sinners, and this becomes a lesson about humanity.”

Conversations can also be viewed as a pleasurable sport. The kind that involves sparring, sharing views, or stumbling on new ideas or feelings. All this without winning or losing. More like animal or child’s play, rather than adult games with outcomes.

Conversations Down the Ages

Jonathan Swift in “Hints Towards an Essay on Conversation” offers certain admonishments. Some of his rules might sound common sensical but are possibly practiced only by a few: “Don’t show off,” “Don’t act too clever or pedantic,” “Don’t talk too much about yourself,” and “Don’t say something you’ll regret later.”

In the 1936, “The Art of Conversation” Milton Wright describes how we can avoid l’espirit d’escalier (“you think of the scintillating remarks you could have made back there if only you had thought of them”). While other techniques might sound manipulative or contrived, Wright ends with: “If you can forget yourself, then you have learned the innermost secret of the art of good conversation.” Of course, this is easier said than done. It’s like telling someone to be “spontaneous.”

Food Fuels Talk

Usually, bars and alcohol are associated with the free flow of talk. But there is also the din one has to contend with at bars. Cohen observes that a certain level of background hum can be helpful. She thinks it might compel speakers to imbue their speech with more force or energy.

In general, she doesn’t recall the most meaningful or longer conversations taking place in bars. Such conversations are best had over slow, long meals. Paula prefers restaurants that offer a cozy ambiance with comfortable seating. The sort that ushers in what the Swedish call hygge. Old-fangled places with candles, dim lighting, and friendly waiters.

As the Dean of the Honors program at her university, Cohen realizes how food can elevate participation in events – at conferences, seminars or other academic gatherings. The food served doesn’t always have to be exceptional or surprising to loosen tongues. Sometimes the quotidian will suffice.

A child psychologist once told Cohen that teens talk better when you take them out for a one-on-one meal.

What are Bad Conversations?

Cohen observes that “bad conversations” are caused by a sense of “inequality” – especially when one conversant acts intellectually superior to the other. No one wants to talk to someone who makes you feel dumb just for saying something.

There are some people who are particularly difficult to talk to or who seem to have nothing to say. For instance, at her parents’ dinner gathering, there was one man who hardly spoke. Till her father started talking to him about M&Ms, the multi-colored candy – the equivalent of Cadbury gems in India. Since the man worked for Mars Inc., this was a topic on which he could wax eloquent. Taking a cue from that, Paula suggests that we can draw out practically anyone if we hit on a topic that’s close to their heart. In her family, the phrase used is: “What are his M&Ms?”

But others, however much they might have to say to anyone else, might find themselves tongue-tied with particular individuals. Apparently, James Joyce and Marcel Proust had nothing to say to each other. Though they were both revered, modernist, literary writers, they detested each other and seemed to share little in common.

Modulating Group Talk

Groupthink over time devolves into grouptalk, where those who remain silent, might disagree but are fearful of expressing their counter-opinions. Richard Wright, the African American writer describes the manner in which opinions were suppressed at a Communist Party meeting in the 1930s.

Sometimes, in the midst of opposing views and uncertainty about where the truth lies, it might help to adopt Montaigne’s position: Que sais-je (What do I know?)

She also suggests that you can quickly tell if a group is open to dissenting opinions or not. If people who hold different opinions are framed as “bad” people rather than just different thinkers. Bad conversations are also ones in which everyone pretends to hold the same opinion on something. On the other hand, arguments that turn into shouting matches are equally pointless.

Conversing Like The French

Learning a foreign language, and perhaps not so well as to speak as flawlessly or unselfconsciously as a native gives one a special status. A liminal state where you are neither an outsider or insider. This goads you to watch the other and yourself, as you rarely would in your own language circles. It affords you what Cohen calls a “double perspective on things.” Paula herself was fortunate to have spent her early twenties in France, a place she finds particularly conducive to conversations.

She recalls having surprisingly literary conversations with French taxi drivers, having discussed Balzac’s Pere Goriot with one, and Stendhal’s The Red and the Black, with another. While one might encounter well-read taxi drivers in other parts of the world, she commends the French educational system for compelling certain foundational texts and a common curriculum on all, fostering a kind of civilized, shared experience that is peculiar to France.

The French also promulgated the idea of literary salons, where men and women would engage in sharp and witty conversations. Women who ran such salons – the salonnieres – helped foment the feminist movement. Many of the salonnieres also had fallouts between themselves, commanding rival factions to follow them.

In contemporary France, the salons have been replaced by cafes, many of which are situated outdoors, with a great view of passersby. As Cohen puts it, her “ideal afternoon” would involve “sitting with a friend in a café in the fifth arrondissement (the so-called Latin Quarter), in sight of the Sorbonne, on a balmy spring day, conversing in desultory fashion over an espresso and a pain chocolat about such topics as the nature of love, the relativity of beauty, and the likelihood of life after death…”

Americans, by contrast, Cohen writes, would be impatient, eager to get to the point. To the French, the conversation is the point. “They’ve had practice sitting in cafes, stirring their tiny expressos, smoking their cigarettes, and letting an idea unfurl at its own pace.”

References

Paula Marantz Cohen, Talking Cure: An Essay on the Civilizing Power of Conversation, Princeton University Press, 2023