The Transformative Power of Mentors And Coaches: Takeaways From A Memoir

Educated by Tara Westover

The year 2018 witnessed the release of two memoirs that corralled global readers into attentiveness. The first one was anticipated: Michelle Obama’s Becoming. The second book streaked into distracted lives like a lightning bolt, numbing all our previous notions about education, family, community, religion and government. With its electrifying account of a child being raised inside a fundamentalist Mormon family in Idaho, USA, Educated by Tara Westover not only reshapes ideas about the makings of a sound education, but also sparks hope about the resilience of the human spirit in the face of unrelenting adversity. More than anything else it shines a light on saviors, on teachers, mentors, counsellors and coaches who can toss psychological hooks to yank the forsaken from turbulent settings.

The Westover Family is Off the Mainstream Grid

To call the Westover home ‘turbulent’ is to put it mildly. Tara was the youngest of seven children raised by parents who deliberately shunned the scaffolding proffered by mainstream institutions. Even before Tara had been born, her brothers were withdrawn from school. “In the four years that followed, Dad got rid of the telephone and chose not to renew his license to drive. He stopped registering and insuring the family car. Then he began to hoard food.” The Westover children, mostly birthed at home, in appallingly infectious conditions, were not registered with any government body. As a result, Tara did not possess a birth certificate till she turned nine. Many years later, Tara would diagnose her father as a bipolar sufferer, and her mother as being anxiously (and dangerously) complicit in Gene Westover’s crazed theories about the evil Illuminati that lurked everywhere.

All the choices that her Dad made on his family’s behalf – to not educate his kids, to completely shun mainstream medicine, to compel his children into hazardous forms of labor – would mould the Westover kids differently from others in the neighborhood. While some other Mormon families also skirted mainstream medical interventions, perhaps none inhabited the intense peril that Tara and her siblings experienced as normal everydays. Driven to undertake rash journeys in treacherous snow storms, or to feed metal scraps into terrifying machines, the family witnessed ghastly accidents – gashes, third-degree burns, skull fractures, brain injuries – all of which were treated by Tara’s mother’s nebulous poultices and fragrant oils.

Tara Directs Her Own Learning

Since learning in their house was self-directed, and actively discouraged by Gene, Tara plotted her escape into higher education in the furtive manner in which other teenagers might stash drugs or drink alcohol. “When Dad saw me with one of those books, he’d try to get me away from them.” It wasn’t like their house was even filled with books. All they had were religious texts, the Old and New Testaments, the Book of Mormon and other obscure letters and journals belonging to early Mormon prophets. The language was antiquated, obscure even for school-going kids. Tara continued to wrestle with those texts, with philosophical abstractions that eluded her understanding: “The skill I was learning was a crucial one, the patience to read things I could not yet understand.”

Eventually, when Tara did make it into Brigham Young University, she had to contend not only with the absence of any education, but also with the alien mechanics of college. For instance, at an Art History course, she did not realize that one had to read the textbook and not just look at the pictures in order to pass the final exam. She grappled with college-level history without knowing what the ‘holocaust’ entailed, what the American Civil Rights movement had achieved or even who Martin Luther King Jr. was. Then, there were ongoing financial strains. She realized, as many other economically fragile students do, that “curiosity is a luxury reserved for the financially secure: my mind was absorbed with more immediate concerns, such as the exact balance of my bank account.”

Supporters And Mentors Proffer Lifelines

One of her early supporters was a bishop at a church near college. He had a sense that Tara had grown up in an unusual family, and was more antsy about dating men and forming relationships than other women in his congregation. Besides listening to snippets of her disquieting story, he also offered her money to bridge her college expenses. But Tara, raised to distrust strangers and also be weirdly self-reliant, refused his checks. Eventually, the bishop persuaded her to apply for a government grant. When she received $4000 from the government, she was shocked by the amount. She called the government office and reported her issue. At first, the lady officer on the line was speechless. She then said, “Let me get this straight. You’re saying the check is for too much money? What do you want me to do?”

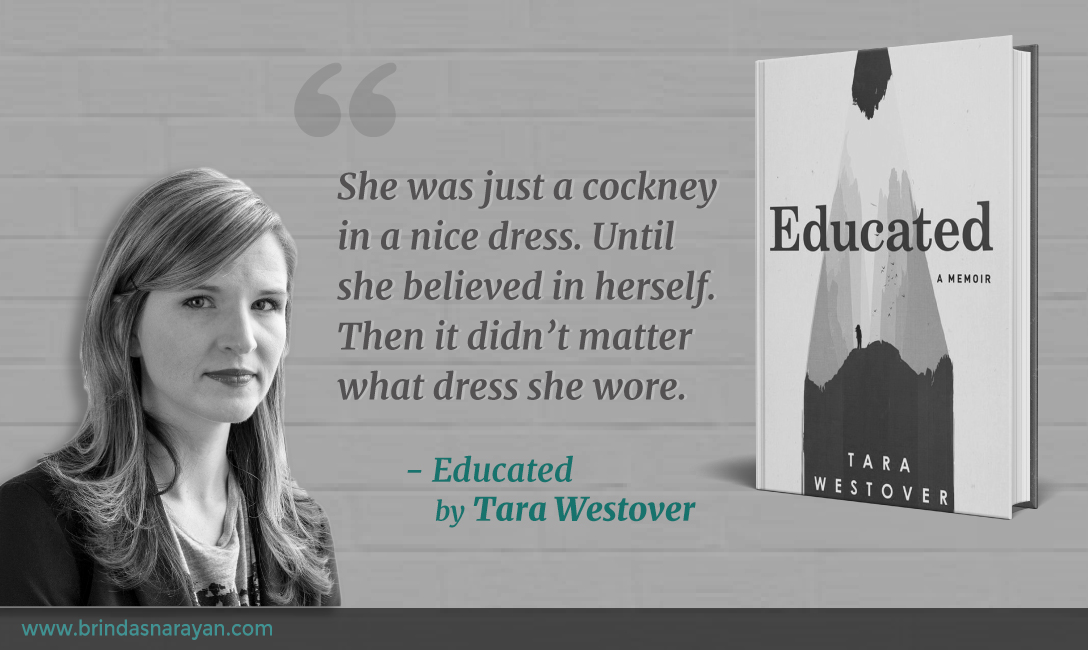

Another lifeline was extended by a history professor, Dr. Kerry. Recognizing the latent talent in Tara, he persuaded her to apply for a study abroad program at Cambridge University. Though Cambridge rejected her application, Dr. Kerry intervened on her behalf and ensured her a place in the program. Dr. Kerry had also spoken about Tara’s lack of schooling to another Cambridge professor, Dr. Steinberg. Like Dr. Higgins in the popular My Fair Lady, Steinberg took the brilliant student under his wing. When she submitted her history essay, she expected it to be ripped to shreds. Instead the professor shone a torch on her genius. “I’ve been teaching in Cambridge for thirty years,” he said. “And this is one of the best essays I’ve read.”

Yet Tara felt like a misfit, a sham. She dwelt on her odd clothes, on the weird jobs she had performed all her life, the absurd family she had been raised in. But her professors refused to give up on her. In a stirringscene, when Dr. Kerry sensed Tara’s unease with her appearance, he reminded her of Pygmalion (the Bernard Shaw play, that was later adapted into My Fair Lady): “She was just a cockney in a nice dress. Until she believed in herself. Then it didn’t matter what dress she wore.”

Later, she won a Gates Scholarship to study history at Cambridge and then a fellowship at Harvard. But her education was bigger than the PhD she was eventually granted. It lay in the belief that she could shed her past and transform herself. That she could become the person she wanted to be and transcend the persona her circumstances had thrust on her.