The Price of Immortality

The Immortal King Rao is many things. It’s a bildungsroman for sure, graphing its narrator’s life, from her strange birth to her present predicament, where she claims to be unjustly imprisoned for a crime she did not commit. Her release will be determined not by a black-robed judge or by a dozen jurors, but by the Algo – which feels eerily like a stand-in for the way an abstract technocracy increasingly steers our lives. Athena, the protagonist, is King Rao’s daughter.

Even as she awaits her verdict, she constructs her defense, sashaying between her own secretive and confined upbringing on an island and King Rao’s past. The “King” of the title is thought to be immortal, as some billionaires might currently seek to be. Athena, who was raised by her geriatric, single father, knows otherwise. She knows that the one-time seemingly infallible and all-powerful CEO of Coconut (think Google or Apple) is like any other loftily titled being: merely human and mortal.

Drifting between a dystopic future – where a phenomenon called Hothouse Earth is gradually subsuming the planet – and the past in a coconut farm in Kothapalli in Andhra Pradesh, the book is part Sci-fi, part fantasy. It’s also a multigenerational saga that crisscrosses continents and time zones, cultures and generations, even as it lays bare the fissures of class and caste, with lush descriptions and an unsparing eye.

Born into a Dalit family, King Rao might represent the hopes and life paths of many Indians. Who have been raised in places seething with undercurrents, that every now and then detonate into family feuds or inter-caste wars. In spaces, where children have to educate themselves out of everyday frustrations or the grinding ennui of not having enough – not just materially, but also socially. Where education is not so much about self-improvement but a means to eject oneself to the furthest possible shores. Most likely to America, where hungry coders are allowed to wash up for exactly that reason: their long-felt hunger.

Sometimes, especially soon after landing in the promised land, the reality is less glittery than it seemed from afar. King Rao is disgruntled by his shabby dwelling and the plodding work: “You aspire to something all your life, and then you do it and find yourself – it’s shameful even to articulate it – purposeless.” Fortunately for him, his genius is harnessed soon enough by his Professor/Mentor, who is displaced like many originators are, by Rao and the Professor’s daughter, Margie. The duo get married and morph into a power couple – a.k.a. Bill and Melinda Gates – lording over the interior terrains of their customer/citizens, who succumb like we all do to the machinations of Coconut, and its product, Social.

Eventually, they create a version that can be injected like a drug into the bloodstream – wherein the internet can be directly accessed by the brain, with information flashing into the user’s consciousness both at will and sometimes, involuntarily. The product has side effects. Some customers die. King Rao absconds from any responsibility and is ousted by the Board. All this while the Corporation is already doing much more – running all Government services because surely Coconut is more efficient than the bureaucratic grind of public offices. And not just of the U.S., but of other countries, because Shareholder Government, like other services, is a viable export.

While most citizens succumb to the succor of efficiently run services, even if it’s at the cost of being hyper-surveilled and hyper-managed, some inevitably protest. The protestors or Exes are banished from the mainlands to the Blanklands – to islands that will be among the earliest to be submerged, when the floods or ocean rises arrive. The Exes loosely follow the principles of the original anarchist Pierre-Joseph Proudhon, who championed workers’ collectives. They expect to set up a utopic society, that would inevitably draw crowds from the mainlands. That doesn’t happen. Folks pick convenience over autonomy or self-management.

The book touches on many themes – some familiar, and perhaps even tackled by earlier works. Like globalization, climate change, the interconnectedness of everyone and everything. But it also throws fresh light on how the hyperlinked world dilutes the very notion of knowledge. For instance, when Athena hears the word, “puffin”, a particular webpage slides into view: “The image in front of me was from the website of the Audobon Society. I was aware of this, of the source, because the experience wasn’t only perceptual. It also contained information.”

That perhaps is the point: that anyone can know everything, and yet nothing seems meaningful anymore. Or how a poor Dalit can rise to the top of not just a humungous corporation, but even of large portions of the world, and yet die unfulfilled, still questing for an elusive El Dorado.

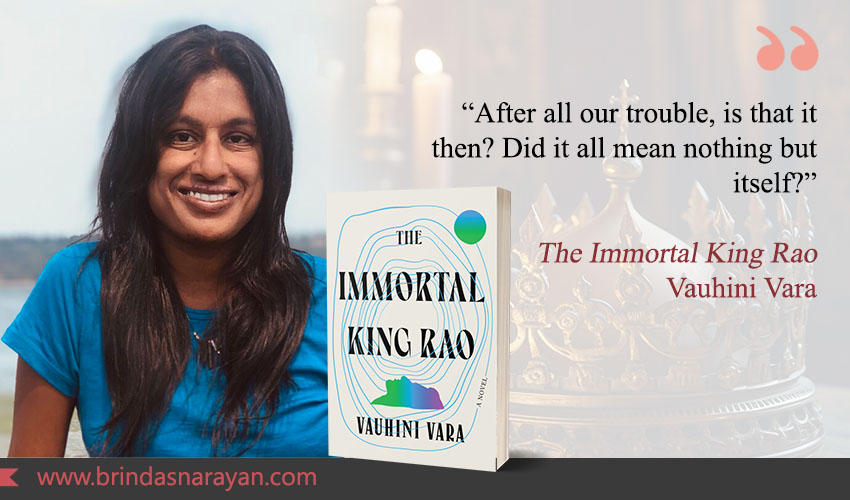

Vauhini Vara, who used to be a reporter at The Wall Street Journal and an editor at The New Yorker, is a fiercely intelligent writer. Her narration is vivid, energetic. She propels you through her pages. Even the older themes are imbued with a new charge, a kind of coursing rage that brings to mind Greta Thunberg’s lashings at the U.N. Climate Summit. It’s redeeming perhaps to recall the young activist’s ongoing optimism and key message: “You are never too small to make a difference.”

References

Vauhini Vara, The Immortal King Rao, Fourth Estate (Harper Collins), New Delhi, 2022