Of An Indian Woman Who Crossed the English Channel

Of late, I have become rather fascinated and even slightly obsessed with endurance athletes. For instance, I recently stumbled on the Netflix movie on Diana Nyad, a woman who swam from Cuba to Florida at the age of 60. So it was intriguing to read about an equally gritty long-distance swimmer, who emerged from India at a time when few women were encouraged to participate in sports.

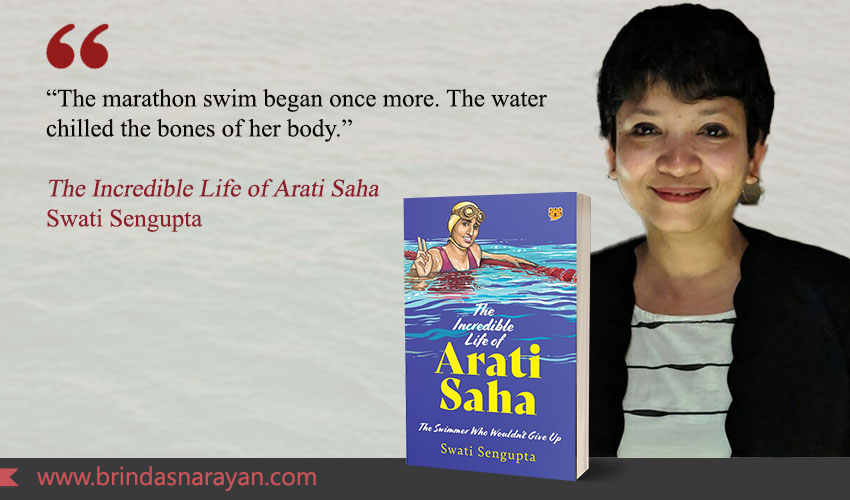

Though the book is targeted at children, this Talking Cub title – The Incredible Life of Arati Saha – can also be soaked up by adults interested in erstwhile female athletes. Besides, it might be salutary for this cricket-dominated nation to recognize that Indians have broken records and achieved physically-impressive feats in other sports.

From A River Bank to a Pool

Arati was only a toddler when she lost her mother. Her younger sister – just an infant then – and older brother were dispatched to her maternal grandparents. Her father, who worked at the army, did not think he could raise three children. So Arati was the only child who stayed with the paternal joint family, taking refuge in her thakuma (grandmother) and kakis (aunts).

This was India in the 1940s, just before the country got its Independence, and faced the upheaval of Partition. Cavorting with a medley of uncles, aunts and cousins, little Arati headed to the Champatala Ghat to bathe every day in the Hoogly River. After all, as Sengupta reminds us, in those days, few houses had water piped indoors. Bathing was always in lakes or rivers.

From her cousins, Arati learned to do doob snataar (swimming underwater). Before long, she was swimming across short distances, without holding onto a floating banana trunk. Her father, still misted over by grief, was struck by her prowess. And decided to send her to the Hatkhola Swimming Club, where there was a large pool.

An Aqua-Prodigy Emerges

At the pool, she quickly mastered all four strokes – free style, breast stroke, butterfly and back stroke. And she practiced relentlessly – swimming in the mornings before school, and again in the evenings after school. At the age of 5, she won a gold medal at a swimming contest in Calcutta. Thereafter, she travelled across places with club officials, winning many more swim races.

Women’s education was just becoming more common by then. The first women’s college, Bethune College, had been set up in 1879 in Calcutta. More women had also starting participating in physical sports. But swimming was not yet considered kosher for women. Before Arati, Ila Sen was one of the first female swimming champions, entering the state levels as a junior in 1937/38.

When Arati was only 8, she lost to the then reigning swimming champion, Dolly Nazir. Dolly was five years older than Arati, so the younger girl’s achievement was astonishing. But Arati wasn’t satisfied. Through salty tears, she set her goals higher. One of her role models was Sachin Nag, a swimmer who represented India at the London Olympics in 1948, despite a bullet tearing through his leg just a year ago. Nag was also one of Arati’s trainers at the Hathkola Club. Many swimmers from West Bengal represented India in the London Olympics (1948) and at Helsinki (1952).

Between 1945 and 1951, Arati won 22 medals in various state-level swimming contests. In 1951, she broke Dolly Nazir’s breast stroke record.

Breaking Into the Olympics

In that year, at the Asian Games held in Delhi, Sachin Nag won India’s first gold medal in the Asian Games. This was in the presence of Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru. Stirred by this, Arati had started dreaming of winning at the Olympics. And one day, Sachin Nag spoke to her after practice, and encouraged her to give the Olympics a real shot. Starry-eyed Arati couldn’t believe her luck. But even after hours in the pool, her timing wasn’t improving. Sachin asked her to reach for shorter goals – to get herself admitted into the Olympics, then try to enhance her performance at the global meet.

Eventually, she was only one of four women picked by India for the 1952 Helsinki Olympics. Her Dad, usually gloomy till then, was also elated. “That made her happy. It was rare to see her father smile.” Four women were picked that year: Arati Saha, Dolly Nazir (swimmers), Nilima Ghose (a sprinter and hurdler) & Mary D’Souza Sequeira (runner). Arati was only 11 years old then, and “the youngest Indian Olympian – a record that stands till this day.” Though none of these women won medals, they were the first women to represent India, post-Independence.

Setting Her Sights Further

Post Olympics, Arati wondered what she should focus on next. She heard of two Asians crossing the English Channel for the first time – Brojen Das (from East Pakistan, now Bangladesh) and Mihir Sen (1958). The English Channel, separating England from France, spans 32 kms and is considered one of the most arduous long-distance swims. Besides, the swim is often longer, since certain tides and currents have to be averted.

By then, folks had started hosting races across the Channel, and in 1958, Greta Anderson from the United States beat both men and women to win it in 11 hours and 1 minute.

Brojen Das created history as the first Asian to win the race. When Arati wrote to Brojen Das, congratulating him on his achievement, he wrote back to her, suggesting she try crossing the Channel herself. After all, she had already participated in the Olympics. Arati was encouraged by her sister Bharati, her cousins and a friend, Arun Gupta. They escorted her to the Dhakuria Lake to practice long distance swims. Arun was 28 and Arati was just 18 and perhaps they were already in love. He planned to help with raising funds for her to travel abroad and participate in the contest. Maybe even accompany her there.

Garnering Government Support

The Chief Minister then was Dr. Bidhan Chandra Roy – a well-respected doctor who was also a friend of Mahatma Gandhi. After putting on a show of resistance, Roy agreed to fund her travel and even relayed Arati’s aspirations to Nehru.

Expectedly, Arun’s and Arati’s families objected to their traveling together, unless they were married. She had no time to fritter on ceremonies and rituals, so they just had a paper marriage, with an intent to celebrate more grandly later. Cheered on by family, friends and even the Chief Minister, Arati set out for England with her new husband and manager.

Arati’s Unyielding Triumph

On the D-Day, Arati’s pilot boat arrived an hour late, and she started out with unfavorable conditions. After swimming 40 miles, when she had only 5 miles left to reach the coast, she battled strong currents and moved forward at a sluggish pace. At that point, the pilot boat lost sight of her and the pilot insisted on dropping the rope to tug her back up. Though Arun Gupta wanted to give her a chance, the pilot insisted it was too risky. Once the rope dropped and touched her, she was automatically disqualified since her swim would no longer be considered unassisted.

Arati was furious to be hoisted up. She felt like she had let down all the people who expected her to finish the race. Determined to try again, she refused to leave England. She started practicing, building up her stamina. On 29 Sept 1959, she plunged into the waters again. This time, she had Arun Gupta vow that he would not allow the rope to be dropped till her saw her dead body floating on the water. “When you are sure I have died, only then lift my body.”

She did it – crossing the lake as it changed colors and merged with the sky. In 16 hours and 20 minutes. Next day, her feat was announced on All India Radio. Arati Saha won the Padmashri in 1960 and was featured on a stamp in 1999. She died at 54, in 1994, of jaundice and encephalitis. She is one of many women whose lives have been interred by history. In this book, Sengupta resurrects an unwavering spirit who dared to swim against the currents of societal expectations.

References

Swati Sengupta, The Incredible Life of Arati Saha: The Swimmer Who Wouldn’t Give Up, Talking Cub, Speaking Tiger Books, 2023