Finding Sisterhood in Our Epics

As a child, I remember reading C. Rajagopalachari’s Ramayana, an English retelling of Valmiki’s epic, that was widely circulated with its calendar arty cover. The centrality of the blue-skinned, unassailable Rama – both on the cover and inside its pages – felt like a given. This, after all, was his story. His almost ascension to the throne, his graceful acquiescence to Kaikeyi’s request, his exile to the forest, the kidnapping of his wife – you get the picture! In an essay titled “Three Hundred Ramayanas”, the scholar A.K. Ramanujan observes that there are innumerable tellings and retellings of the epic. Quite inevitably, women authors have been drawn to reimagining Sita’s story, because surely there must have been currents seething under her self-suffering, wifely demeanor.

Re-Visioning Sita’s Journey

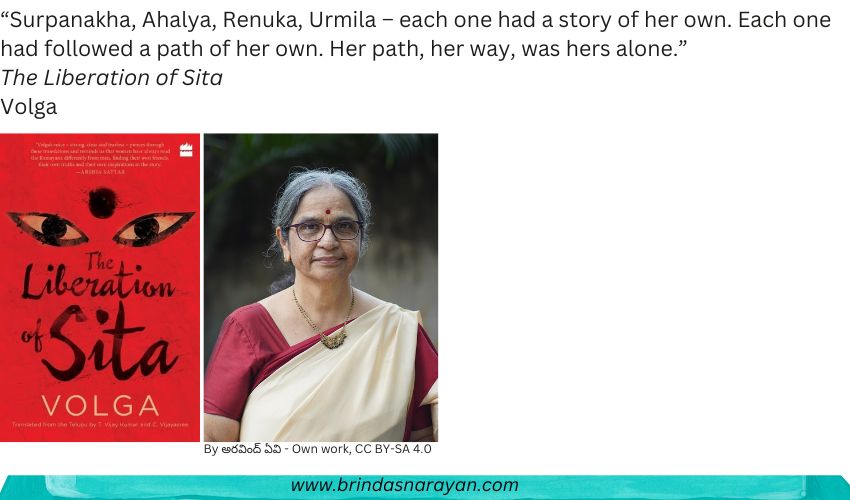

I was recently captivated by The Liberation of Sita by the feminist Telugu author Volga. Translated from the Telugu original Vimukta, the work not only reimagines Sita but a host of other women who were either demonized or marginalized in mainstream narratives. As Adrienne Rich puts it in an essay, “Re-vision – the act of looking back, of seeing with fresh eyes, of entering an old text from a new critical direction – is for us more than a chapter in cultural history: it is an act of survival.”

Surpanakha: Rejecting Body Shame

In “The Reunion”, a banished Sita rears her sons inside Valmiki’s Ashram. One evening Lava and Kusa return with an eye-catching bunch of flowers. Struck by their dazzling find, Sita learns about a garden tended by an “ugly” woman. With the brutal clarity that children possess, they describe her as not having a nose and ears. Sita figures that they’ve encountered Surpanakha, Ravana’s sister, who had made overtures to Rama and Lakshmana. And whose nose and ears had been sliced off by the latter. The craters on her face had infuriated Ravana, whose kidnapping of Sita was an act of vengeance.

Valmiki’s Ramayana does not return to the aftermath of Surpanakha’s life. How did she live with her altered visage, how did she navigate the ravages of men and time? When Sita visits the garden blooming with a profusion of colour, Surpanakha admits that her journey has been filled with strife. Gradually turning away from what she lacks to what she has – her deft and nimble hands – she creates beauty around her. She finds a partner who appreciates her vitality and wisdom, too.

Over time, Surpanakha recognizes that “beauty” and its absence are fleeting social constructs, limiting adjectives that can barely describe Nature with its infinite variety. She transmits her hard-won understanding to Sita, a message that can resonate even in contemporary times with acid-attack victims or body-shamed women: “Everything began to look beautiful to my eyes. I, who hated everything including myself, began to love everything including myself.”

Ahalya: Discovering Inner Strength

In “Music of the Earth”, Ahalya, the wife of a sage, was once visited by Indra. Disguising himself as her husband, he tricked her into surrendering to his lust. Or so it was told, in one version. In Volga’s reimagining, Ahalya retorts with the fury of women – who are often disbelieved in #MeToo cases, or after being raped or assaulted. This is not just about Ahalya’s violation. It’s also about her husband’s response. To him, she’s an object, a piece of property that’s been transgressed. She realizes that for women, erasure of the “ego” requires shoring up inner strength, drawing boundaries, and not handing over authority to patriarchal figures – fathers, husbands, or camouflaged interlopers.

Urmila: Overcoming Negative Emotions

In “The Liberated”, Sita rushes back to Ayodhya after their fourteen-year exile to reunite with Urmila, Lakshmana’s wife. She had missed her co-sister all those years in the forest and exults about meeting her. She’s told however that for fourteen years the latter had isolated herself inside a palace, not stepping out to meet anyone.

When they meet, Urmila tells Sita that she too has been on a journey, even if she’s been confined to her palace. At first, she raged about Lakshmana deserting her without a thought. Gradually, however, she examined her emotions with curiosity: anger, hatred, jealousy, and bitterness. Probing the makeup of her body and mind with a sharp scalpel, she started overcoming what had previously felt impossible: her feelings. Though she had been alone for these 14 years, it wasn’t a sorrowful loneliness or bitter incarceration, but a fulfilling solitude. If Lakshmana had changed after his adventurous forest forays, so had she. She insists, at this point, that he should accept her as she is now. The Urmila that he left behind no longer exists.

Volga’s stories are penned with a startling psychological acuity. The lessons Sita gleaned from these women are relevant to many when a manosphere is engulfing the planet. Her insights are not just for women, but also for men. After all, toxic masculinity hurts all. In “The Shackled”, Volga depicts Rama’s loneliness after Sita abandons him. While rigid hierarchies are visibly problematic for many at the bottom, they can be equally discomfiting for a few conscience-stricken folks at the top.

About the Author

Volga is the pen name of Popuri Lalita Kumari, a feisty Telugu writer and activist, who was awarded the Sahitya Akademi Award in 2015. This edition is translated by T. Vijay Kumar and C. Vijaysree. In an interview with the translators, she says, “Sisterhood is an important concept in feminism. I have been able to grasp that concept through these stories. The other women are all Sita’s sisters.”

References

Volga, The Liberation of Sita, Harper Perennial, Harper Collins India, 2016

Adrienne Rich, When We Dead Awaken: Writing as Re-Vision, Vol. 34, No. 1, Women, Writing and Teaching (Oct., 1972), pp. 18-30 (13 pages), Published By: National Council of Teachers of English