A Modern Retelling of The Drona Ekalavya Story

The Drona Ekalavya story is familiar to many Indians. To reiterate the most commonly shared version, Ekalavya, who belongs to what was then considered a low-caste tribe, desperately wants to learn archery from Drona. The Guru however is forbidden from teaching him, because he’s committed to transmitting his skills only to the royals. Or because Ekalavya belongs to a caste that cannot garner Kshatriya know-how.

Either way, Ekalavya forges a clay statue of the master and achieves an astonishing level of mastery. For instance, he can pierce animals merely by listening to the sounds of their whereabouts. Or stuff a barking dog’s mouth with arrows that can muffle it, without hurting or killing the creature.

When Arjuna, the Pandava prince who’s training under Drona, encounters Ekalavya’s dexterity, he’s stabbed by jealousy. When he expresses his anger at his Guru’s betrayal, Drona pleads innocence. Later when Arjuna and Drona confront the magical stand-in for a physical teacher, Drona demands that Ekalavya slice off his right thumb as Guru Dakshina. An act that would immortalize Ekalavya as one of the most fervent learners in Indian mythology.

In a version cited by Saikat Majumdar in The Middle Finger, the tale has a twist. In this variant, it’s not Drona, but a crafty Arjuna who demands that Ekalavya severe his right thumb. When Drona hears what Arjuna has done to the poor Bhil, he blesses Ekalavya with a special gift. He would be able to shoot arrows “using his middle finger and his forefinger.”

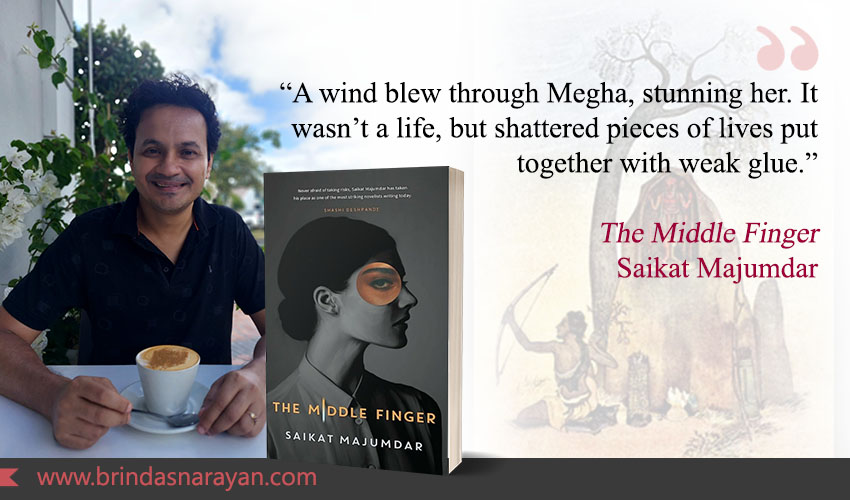

The book itself is a modern retelling of the Drona Ekalavya story. Centered around a contemporary poet and writing teacher, Megha, the book explores the manner in which knowledge or skills can transmit to eager learners, even without the conscious connivance of mentors or teachers. And how such osmosis can explode interpersonal boundaries between the mentor and mentee, leading to a relationship that liberal institutions champion in theory but rarely beget in practice.

Majumdar begins with a tantalizing and baffling dip into the interiority of another character, Poonam, who lives amidst the shrill cries and bloodied carcasses of a meat market, whose poetic ear seems destined to be blocked. As many voices possibly are, among those who perform critical but rarely lauded labor: domestic work, garbage pickups, tinkering in small repair shops, selling chickens.

Poonam sleeps entwined around her sister-in-law Swapna, widowed by the death of her alcoholic husband. As Saikat suggests, in this group especially, where the men are either drunk or dead, women are each other’s succor. Poonam observes: “I eat meat. But Swapna’s pain has become mine. In this room, death is shaped like a window.”

Megha, who occupies more significant chunks in the narrative, couldn’t be more different. She epitomizes global cosmopolitans, a lot who tend to think like the “Anywheres”. (In his book, The Road to Somewhere, British journalist David Goodhart describes the emergence of two sets of people in the UK. The globe-trotting set, the “Anywheres” who prize “autonomy and fluidity” versus the “Somewheres”, the poorer, less educated class who cherish “group attachments and security.”) With an eye on how such divisions play out in India, Majumdar introduces us to Megha, when she has already dropped out of her PhD at Princeton.

As a poet, she’s attuned to the fissures of class in America. As a foreigner perhaps, or as a woman of color, or as a writer who is self-conscious about her own privilege, she chooses to live in New Brunswick and teach writing at Rutgers. She senses how the less prestigious university is more diverse. The lauded Ivy League seems too removed from the real world that poets hope to impact or draw inspiration from. “Princeton; for all the grad school years, was Nassau Street and its boutique cafes and bars and bookshops, Albert Einstein’s retirement home looming close by. The spires of Firestone Library, Hogwarts for adults.”

But writers are like leeches. So is Megha, who sucks in her students’ stories – their honest, confessional, even cathartic spills of personal life – and spits them out as poems. She’s empathetic and imaginative. Students gravitate towards her, and they grant her more of what she seeks: their woes and slights. All of which seep into her consciousness and wriggle out like worms. She recoils at the injustices meted out to them.

Her poems “came from anger and hissed like droplets on hot metal.” But she’s also remorseful about using her students’ tales like this. She gains followers, online and offline. Her guilt is peculiarly magnified when she hears her poems being performed – read out aloud at smoky basement bars or on Instagram.

Hearing them sounded out by others jolts and repels her. She even rushes into a restroom once to skirt the mortifying ordeal. Giving voice to an ethical dilemma that might confront some or all writers – whose stories are you allowed to tell? – Megha “felt she was claiming a pain that wasn’t rightfully hers.”

Yet, her poems seem searingly felt, and they continue to emerge from her in good times and bad. When she breaks her elbows and is imprisoned inside her high-ceilinged, studio apartment, the bleak circumstances “[push] poetry out, fine and slimy.” Breaking away from her Rutgers teaching life, she returns to Princeton on a fellowship, where she dabbles with the thought of finishing her dissertation. And doesn’t.

Instead, she’s tugged to Delhi by friends – cosmopolitans like her – the white Tamil scholar, Rory, and his Wellesley-educated partner, Lasya. They draw her into Harappa University, a strong liberal arts college, similar perhaps to Ashoka University or FLAME. In this place, Indian students are encouraged to pursue their passions, in the Sciences, Social Sciences or Humanities. Lasya tells Megha: “If you come to Harappa, you’ll be struck by the energy of the students. I’ve never seen something quite like this before in India.”

Her sojourn in Delhi changes Megha in unexpected ways. She is, perhaps, at the end of the book, less “pretentious” than she might have been at the beginning. The gawking “Somewheres” accord her with a rootedness that the “Anywheres” often grope for. She even dredges up her forgotten dissertation and breathes life into it.

The Doctorate, ultimately, is less significant, than her deeper awakening. I don’t want to give away the ending to potential readers, but it’s a journey that forces an association with the “other” that extends beyond glib talk about Simone de Beauvoir and Foucault.

After teaching at Harappa for a year, Megha addresses a class of hopeful 11th and 12th graders. Some might emerge from elite, international schools, others from ICSE or CBSE settings, and many more from state boards, from small towns and rural areas. From families whose parents may have never attended college themselves, whose English might be faltering, and whose mastery of Hindi and other Indian languages may be strong.

Whose eagerness to learn might mimic the original Ekalavya’s. Yet they might be held back from dreams because they ferry centuries of internalized shame. It’s them that Megha especially speaks to: “I want to make the shamed ones the spine of this university. I hope all teachers will think of you as the rule. The rest should be the exception.”

Saikat is a deft writer. Like the poet character he describes, he polishes his lines till his words glisten. He also portrays his woman protagonist with credibility, not an easy feat for many male authors. He nails her voice, as he does Poonam’s, a more difficult character to inhabit.

Majumdar himself is currently a Professor of English and Creative Writing at Ashoka University. You also sense that with sensitized teachers like him, the nation is poised to unleash many more talented voices. It’s our job as readers or listeners, to stay attuned.

References

Saikat Majumdar, The Middle Finger, Simon & Schuster India, 2022

David Goodhart, The Road to Somewhere: The Populist Revolt and the Future of Politics, Hurst & Co., London, 2017