Re-examining the Roots of Patriarchy

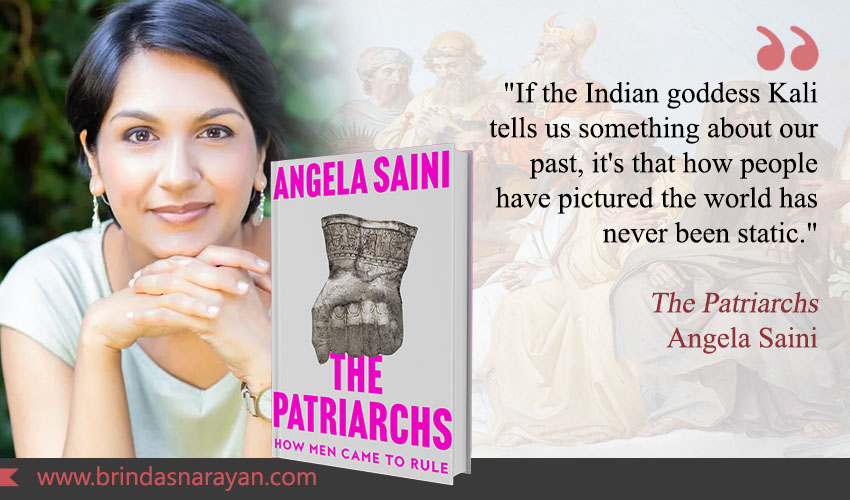

Angela Saini approaches the past with an engineer’s precision: foraging inside historical, archeological, and anthropological records for real glimmers of how things were. This is unsurprising. After all, she holds two Master’s degrees. One in Engineering from Oxford University and another in Science and Security from the Department of War Studies at King’s College, London. She also wields words with an aesthete’s finesse. She capped her Master’s degrees with a Knight Science Journalism fellowship at MIT. Her works inject freshness into our readings of the past, particularly when it comes to commonly held beliefs about race and gender.

In Inferior, published in 2017, she exposes the manner in which society has often overplayed biological differences between male and female brains. Of how science has never been as objective as it might claim to be. Even greats like Charles Darwin were blind to social factors accounting for female invisibility in these fields. In her next book, Superior (2019), she uncovers how implicit racist biases can affect scientific outcomes. For example, drug trials are often conducted separately across racial categories. But is that always the right way to conduct such trials? Some findings might be a result of economic or social conditions. Or of ecological environs. As a scientist, you might be asking the wrong questions, if you don’t interrogate historical practices or ways of seeing.

In her latest work, The Patriarchs (2023), she delivers what might be considered a more optimistic outlook for those who aim for gender equality. After all, when studying systems around the world, there are several prehistoric or premodern setups in which women wielded more power than they currently do. Even in Neolithic communities – around 7400 B.C. – there are examples of gender-blind societies. Like in Catalhoyuk in Anatolia (contemporary Turkey). Or in the Peruvian Andes, where the body of a female hunter was discovered. Which belies the notion that men always did the hunting and gathering, while women tended to home fires and kids.

In colonial times, Saini notes that transgressive Indian goddesses like Kali were feared and abhorred by the British. In a publication of the Bible Churchmen’s Missionary Society, a British woman shuddered at the corpse-slaying, skull-donning Goddess. “What an awful picture!” she wrote. “Yet this savage female deity is called the gentle mother!” Today, Kali is acclaimed by feminists for exactly that reason. Because women, like men or others across the gender spectrum, can combine contradictory traits. Being a nurturing parent does not preclude the capacity to wield power.

Angela also ponders our need to keep looking over our shoulders into conceivable pasts, in order to feel more hopeful about our future: “When we look to Kali, I wonder if we’re reaching for the possibility that there was a time in which men did not rule, a lost world where femininity and masculinity did not mean what they do now.” Such an act, Angela senses, stems from a feeling of impotence in many contemporary settings. After all, patriarchy can often feel permanent, massive and unchangeable. But we forget how recent these structures are, and hence as tractable as everything else that’s manmade.

Besides, as Saini points out, we mustn’t assume that patriarchy is good for men. Rigid gendered norms hurt everyone. In the current conflict with Ukraine, for instance, many young Russian men are being conscripted into war. Some or even many might be unwilling to fight, but they happen to belong to the ‘wrong’ gender in this situation. Moreover, the pressure to be eternal breadwinners or physically stronger or emotionally tougher can be as detrimental to masculine psyches as the opposite can be to feminine ones.

Patriarchy also assumes different forms, based on specific histories and cultures. If mere biological differences were to account for patriarchy, one wouldn’t encounter so much variation across societies. To further shatter assumptions of what caused human beings to settle into this kind of gender ordering, Saini dwells on the exceptions: “Evidence across cultures proves that what we imagine to be fixed biological rules or neat, linear histories are anything but.”

Studying exceptions among human societies, Saini observes matrilineal or matriarchal formations in Kerala (among the Nairs), in other parts of Asia, in some terrains in North and South America, and across a broad swathe running through the middle of Africa. It’s only in the so-called seat of “civilization” or the center of “Enlightenment” – Europe – in which matrilineal orderings are almost completely absent.

We mustn’t think, as Angela quickly points out, that men have it all bad in matriarchal orderings or that women have it all good. But such societies help to elevate the position of women and question deeply problematic assumptions in others. As the historian Manu Pillai writes of Nair women in The Ivory Throne, “Widowhood was no catastrophic disaster and they were effectively at par with men when it came to sexual rights over their bodies.”

It was partly the European gaze and court rulings during colonial times that started dismantling Nair family structures. Some Western scholars also framed such ways of being as a “matrilineal puzzle” – as inherently unnatural.

A tribe that remains matrilineal in current-day India is the Khasis of Meghalaya. Interestingly, some Khasi men started a “men’s rights” movement. But the Khasi writer David Roy Phanwar celebrates their tribe’s ordering, where “the woman is the glorified person, free to act.”

Of course, we cannot assume that matriarchies are idyllic or utopic by any means. It’s not like all women are gentler, more compassionate, closer to nature, or peace-loving. Saini in fact highlights that patriarchal forces often devised such “essentialist” attributes associated with women. Which are annoying for women too, since they’re not in consonance with our lived realities. But she’s hopeful that the “fight for a fairer and more equal society” will continue to remake itself. In ways that are as inventive as the forces against it.

References

Angela Saini, The Patriarchs: How Men Came To Rule, Harper Collins India, 2023