Between Peaks and Poetry: Journeying with Edward Lear

Chronicling an Artist’s Quest

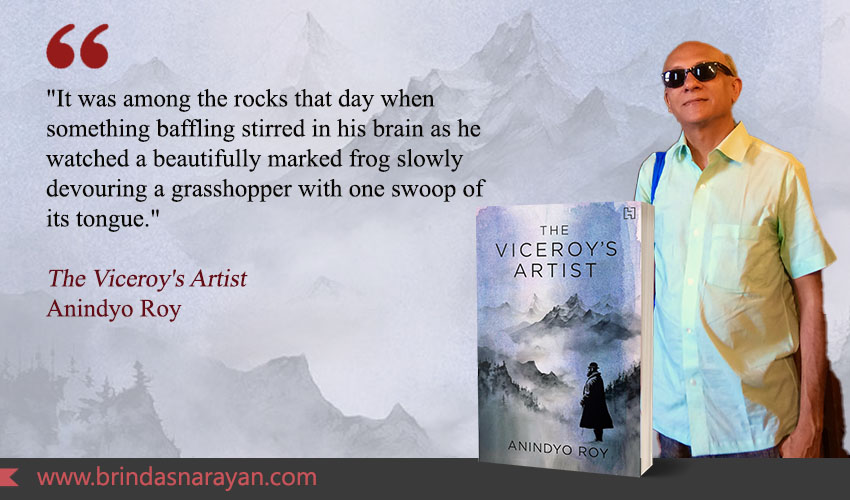

I recall learning “The Owl and the Pussycat” for an elocution contest. And encountering the nonsensical, memorable “Piggy-wig”, which had merrily enough for us chuckling readers, “a ring at the end of his nose.” The author of this well-known poem, Edward Lear, was an Englishman with the kind of vivid imagination and writerly empathy that the British Empire sorely lacked during the height of its colonial domination. In The Viceroy’s Artist, Anindyo Roy, an Associate Professor of English, Emeritus at Colby College, rekindles a specific period in his life.

Digging into the journals of a man who was not only a poet, but also an artist, illustrator and gutsy traveler, the book lays bare the contradictions experienced by those Englishmen who were too sensitive to overlook the hypocrisies levied by the Empire. It’s also a work that evokes how the constant intermingling and jostling between people belonging to vastly different cultures and ethnicities can engender surprising and pleasurable common grounds. Like the orientalized James Kirkpatrick in William Dalrymple’s White Mughals, Lear clearly belonged to a tribe of creative misfits. Who was seeking through his zigzag wanderings, not just objects for his art and poetry, but also perhaps something that he consciously missed: a place he could call home.

Painting Himalayan Peaks

Lear reached India in 1873 after spending time in many other places. Like in Palestine, Jerusalem, Italy, other parts of the Middle East. In India, he had been accorded with a special mission. To paint the Kanchenjunga or the Eastern Himalayas, from Kurseong in West Bengal. The then Viceroy of India, Thomas Baring, also known as the 1st Earl of Northbrook had commissioned the piece after encountering Lear’s landscapes in Rome.

Physically, as Roy uncovers, Lear was anything but agile. He was a portly man, who suffered from occasional epileptic fits. Carting him to points where he can get an optimal view of the peaks was an uphill task for Giorgi, his manservant, a “Suliot from Corfu.” Giorgi accompanied his master across geographies, abiding with calluses and illnesses induced by such journeys.

When Edgar Ware, the assistant commissioner in Kurseong, sent Lear a note suggesting he head directly to Agra, avoiding Bihar – because there was a famine in Bihar, Giorgi dryly observed that he was familiar with famines. He had already lived through one.

Lear recalled a conversation with Evelyn, the Viceroy’s personal secretary, wherein the latter had flippantly referred to a gardener who had survived a famine. And another who had emerged from a hurricane that destroyed his village and family. Evelyn, who was also a Viceroy’s cousin, attributed these mishaps to the chanciness of nature in the tropics. But Lear could not help wondering if the British were more responsible for all this than they were willing to concede.

Wrangling With Artistic Choices

Like many artists, Lear wrestled with self-doubt. As someone who had illustrated Alfred Tennyson’s poems, he even had a confidence-bolstering missive sent to him by the famous poet: “With such a pencil, such a pen, You shadow forth to distant men, I read and felt that I was there.”

When finally staring at the daunting Himalayas, he wondered how he would capture the middle ground. The space between the clearly delineated ranges, and the visible ferns and foliage closer to his easel. It was the elusive in-between that many landscape artists struggled with.

As Roy lyrically writes, when you create art, you also learn to capture emptiness. The play of light. The interludes between action, the silences between noises. Lear wondered if he should turn his watercolours into oil paintings, but then he also worried about how he would fund all this. He was curious too, like any Master might be, about what Giorgi really thought of him. Did he notice that Lear’s faculties were gradually fading, his energies tapering off? For how long could he remain a “diligent vagabond” as Tennyson had called him?

Lear’s Contrarian Vision

On one of his traipses, he bumped into the aggravating Mr. Perry, who managed a tea estate. Who could speak of nothing else but the diseases one would catch in India. Who warned of the digestive dangers that awaited one. Who believed that Banaras – a city that Lear had already visited to paint the Ghats – should be avoided at all costs. Who insisted that India was only worth visiting for the game in the forests, bridge games and tennis matches. Perry was one of those self-righteous missionaries, so sure of his own supremacy. Later on, when he reached the dak bungalow, Lear composed a rhyme about the aggravating, smug man:

If I were a cassowary

On the plains of Timbuctoo

I would eat a missionary,

Prayer Book, Bible and hymn book too.

Unlike most of his compatriots, Lear had a vivid imagination. He took great glee in the wonderful ferns and amazing insects around him. For instance, in the “golden tortoise beetle” – its body “folded in a glittering glass shell.” He could also take off his glasses to return the world to its “magical fuzziness” – an act that would allow him to take in the sounds more sharply. Sometimes, he spent time with the fantastical, nonsensical creatures from his own pages: with Meritorious Mouse, Abstemious Ass or Fizzgiggious Fish.

Whiskered Whimsy: Lear’s Connection with Children

Lear had a special relationship with children. They loved toying with his beard. They talked to him about his nonsense poems. They showed him their drawings. Because he understood and perhaps thought more like them than like any of the adults around. He noticed stuff that they would notice. For instance, at the Taj Mahal, he was as bewitched by a dressed-up monkey surrounded by squirrels as he was by the marble monument that he described as “altogether Indian and lovely.”

Though the Empire has been long dismantled, escapes into Lear’s fantasy worlds, or into this sharply recreated, lyrically penned slice of the past remain as beguiling as his artful limericks.

References

Anindyo Roy, The Viceroy’s Artist, Hachette India, 2023