Linking Time and Beauty with Physics

Adrian Bejan: A Brief Dip into His Story

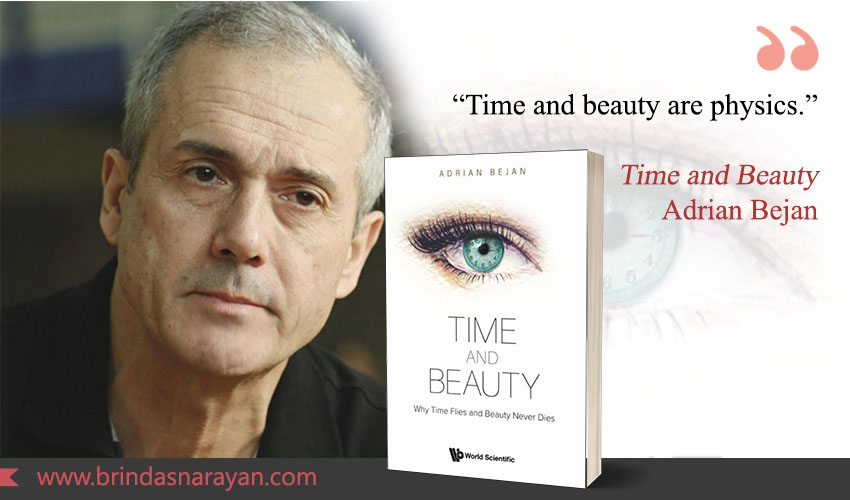

I rarely pick up books written by engineers. Time and Beauty is an exception. Though its author is not just an engineer, but a dauntingly accomplished one, the book called out to me for several reasons. The topic, of course, but also the author, who is anything but a conventional engineer.

To begin with, a brief dip into the author’s background. Currently, Adrian Bejan is the J.A. Jones Distinguished Professor of Mechanical Engineering at Duke University. Hailing from Romania, he had demonstrated a remarkable talent for mathematics and had been admitted to MIT at 19. His undergraduate and graduate studies were in mechanical engineering, with a focus on thermodynamics.

As a professor at Duke since 1984, he’s written a ton of books (30) and peer-reviewed papers (700). Many of his textbooks are considered seminal in the field. Some folks have even coined a term called the Bejan number (Be) named after him.

Discovering the Constructal Law

In 1995, at a conference in France, he heard the Nobel Laureate Ilya Prigogine speak about branching patterns in nature, such as those found in trees or inside the vascular systems of animals. Prigogine posited that these patterns were similar because of a “coincidence.” But Bejan wondered otherwise. What if there is some underlying principle leading to these tree-like structures? The theory he then came up with is called the “constructal law”

As Bejan puts it, nature’s designs are not accidental but emerge spontaneously to enhance access to flow in time. Bejan has applied constructal theory to diverse fields such as social interaction, economics, and urban infrastructure, demonstrating its usefulness well beyond thermodynamics. He was even consulted by the British government on the application of constructal theory to the flow of information between citizens and the government.

The law encompasses blood circulation and riverine flows, as it does transportation networks and power grids. The law can be leveraged by fashion designers, city planners, sustainability champs, energy conservation folks, and many others.

A Few of His Other Papers

After encountering his latest work, Time and Beauty, through an online talk, I ran my eye vertically down the long list of papers he’s published. There is, of course, the paper that became hugely popular before the pandemic recast time for all: “Why the Days Seem Shorter as We Get Older.”

Time is not the only topic that stokes his curiosity. There’s also: “Why humans build fires shaped the same way.” If you’re looking to build a fire that’s going to burn for as long as possible, you’re better off arranging dry logs in a pyramid shape. In other words, as Bejan suggests, you must ensure that “the base is as wide as it is tall.”

Then there’s “Why we want power: Economics is physics.” Bejan compares systems like river flows to other vascular designs – for instance, the stuff that grows inside an eggshell when a chicken’s embryo is developing. He observes that the pursuit of efficiency does not result in lower power consumption, but rather in the converse. I could not access the rest of that paper (it’s locked into an academic journal), but it’s a must-read for anyone interested in sustainability.

Here’s another fascinating question he pursued: “The evolution of speed in athletics: Why the fastest runners are black and swimmers white.” For once, the answer is not purely historical and cultural. According to anthopometric studies, the “center of mass in blacks is 3 percent higher above the ground than in whites.” Because of this, blacks are endowed with a 1.5 percent edge in running, while white athletes possess a similar advantage in swimming. Building on this notion, Asians can overtake whites in swimming, but they are held back by their relatively shorter stature.

There’s also the physics of University Rankings, “The Physics of Spreading Ideas” and a whole host of other realms that you may not have linked with physics at all. In a talk titled, “Freedom, Beauty, Evolution and Nature” he observes that stuff is more related (or interlinked) than we think. For instance, he juxtaposes images of a river basin with a human lung to demonstrate that both have arborescent (meaning, like a tree) architectures.

Connecting Time and Beauty with Physics

In Time and Beauty, subtitled “Why Time Flies and Beauty Never Dies,” he does it again. Builds bridges between concepts that are rarely connected by others. Bejan had already contributed insights on beauty in the past. He proposed that a golden ratio (where L/H = 3/2) was pleasing to the human eye because it was easier for the visual system to assimilate. This ratio is visible across monuments, artworks, faces and in nature.

It’s also the reason that most museum and gallery exhibits tend to be horizontally elongated rather than vertically stretched. Since our two eyes tend to scan the world in horizontal snapshots, we apparently prefer that shape.

Bejan distinguishes between “mind time” and “clock time.” Mind time is our internal, subjective sense of the passage of minutes and hours. And mind time speeds up as we age. This is because our ability to process images degrades, and hence we assimilate fewer images in a single day than in our youth. As each 24-hour period absorbs less of the world, time seems to flow faster. It’s also the reason why infant eyes move rapidly from here to there.

Beauty continues to attract because beautiful images are easy to process. As the Professor notes: “Time and beauty are physics.” Dwelling in the beautiful, whether with an artwork or in a tree-filled landscape, can help slow time, since we’re able to take in more images.

Also, as human beings, we tend to ignore the humdrum and pay more attention to surprises. It’s inevitable then that we absorb more in a new place (like when we travel) when mind time slows down. As Bejan suggests: “Time represents perceived changes in visual stimuli.”

For those of us who may not be able to travel or engender other pleasant surprises, Bejan offers tips on how he slows down time for himself. To begin with,

· He consciously observes the world in all its granular detail

· He writes and draws by hand

· He engages in creative work – in other words, in work that’s not repetitive.

More than anything else, he says: “I value each day as if it were my last one.”

References

Adrian Bejan, Time and Beauty: Why Time Flies and Beauty Never Dies, World Scientific Publishing, 2022

https://www.vox.com/2016/7/20/12212472/what-is-fire-campfire-summer-camping-how-to