Tasting the Divine: Exploring One’s Faith Along The Ganga

Culinary Soul Search

In October 2015, Siddharth Kapila decided to quit his law career. He wanted to travel, find himself, engaging in seemingly care-free acts that only the reasonably well-off can consider. He was aware too of how these choices were girded by privilege. He travelled to Japan, Greece and Italy, chomping his way through the distinct culinary offerings of each place. Akin to an Eat Pray Love experience that involved, as he puts it, “Question, Investigate, and sometimes Pray.” At the end, he felt he wanted to investigate something that was achingly familiar, yet inadequately explored: his own country, his home. “The more foreign cultures I tasted, the more I yearned to dive deeper into my own.”

Revisiting Yaatras

Growing up, he had accompanied his feverishly-religious mother on many yaatras. Recently to Dwarka, Jagannath Puri and Rameshwaram. With an eye-rolling, sometimes grudging acquiescence to her ritualistic asks. This time around, he decided to embark on his own yaatras and write about them, marrying past and present, while interviewing fellow-seekers. Sticking to Hindi-speaking spots along the Ganga (as a North Indian, he felt more comfortable in Hindi), he set out on this midlife foray. Starting out in the Himalayas – the chota char dham – he planned to descend into Rishikesh, then to the Kumbh Mela in Allahabad, ending his journey at the Ganga Sagar in West Bengal.

Faith On Edge

Segueing between past and present – mimicking the deceptive sameness, yet ongoing alteration of the river – Tripping Down the Ganga records vignettes from Kapila’s journeys, some as an angsty teen, others as a more reflective adult. Like when he travels with a Pandit from Shivsagar Ashram in Rishikesh. The Pandit was 34, the same age as Siddharth. But needed to be accorded the respect of an elder. While their Innova tumbled to Kedarnath, all along the Panditji muttered the Hanuman Chalisa till he felt sick, highlighting how faith and fear often totter together on a thin edge.

Pilgrims Old and New

Kapila wrestles with his own ambivalence towards spirituality and religion. Raised among contentious views – his mother’s ardent belief in Sanatan Dharma, her unshakeable devotion to a Guru in Rishikesh and his father’s staunch atheism – Siddharth hasn’t made up his mind about his own leanings. At times, his mother seemed easily taken in: “Her penchant for dishing out large donations had made her very popular with saints and imposters alike.” But he’s not sure if his father’s rationalist world view captures the ineffable magic that might pervade everything.

He recalls a 1998 yaatra with his mother and his maasis, when everyone chanted across the rickety rides, their prayers and pleas and mantras growing louder and louder. Siddharth and his friend Arjun watched their devout co-passengers, with a shade of amusement and irreverence. But some of that faith seemed to infect them too.

In 2016, the yaatra-scape has morphed. Heli-yaatris, people who make the trip by helicopter, overtake those on foot. But perhaps such one-upmanship comes at a cost. There are beliefs that the rich yaatris won’t get what they seek, unlike the poor yaatris who climb barefoot. There are also rumors that Kedarnath has been corrupted – with prostitution, liquor, slaughtered goats. The natural calamities are blamed on such corruption. The reach of digitization extends to the icy slopes. When panditjis offer to conduct an abhishek and you refuse, they fish out handy business cards, suggesting you connect on WhatsApp.

The all-pervasive presence of the Tech Gods or high modernity appear in other incongruous spaces. Enroute to Badrinath, their driver plays Pitbull’s “Give Me Everything Tonight” – the lyrics epitomizing the plea of the faithful and faithless. With Siddarth’s thoughts again seesawing between his mother’s fervid Faith (she had capitulated, like many others, to 1995 rumors about Ganesha’s milk-guzzling abilities) and his father’s dogmatic Reason, he wonders if there is something “blazing beyond the sum of all intellect and imagination.”

Epiphanies On Peaks

At times, the rackets cease to bother. When Kapila spots the white peaks, with the River Mandakini coursing through the slopes: “There was a convergence here – of geography and biology, of world and spirit.” At Badrinath, while praying intensely to Vishnu, he senses he is being commanded to work with his hands: to cook and to write. He’s shaken again by the cloud-slicing Neelkanth Parbat, or the diya-lit Alakananda River, a sinuous shimmer at night. In other moments, the doubts resurface: “Isn’t order a meaning we attach to the innately stochastic?”

Karmic Dissonance

Such journeys can involve plumbing discomfiting questions. When traveling with Theo, a young German backpacker and a Pandit, Siddarth and Theo ask the Pandit why sweepers seem to be forbidden from entering the temple at Badrinath. The Pandit expands on “karmic” roles assigned to different folks, leaving Kapila disappointed. Since he had invited the Pandit as a guest, he lets the matter slide.

Plumbing The Self

Kapila’s journey along the Ganga wasn’t just a religious or spiritual one. It was also about coming to terms with his identity. In 2008, he came out as gay to his mother. Taking solace in androgynous figures in Hinduism – the Ardhanarishvara form of Shiva and characters like Shikhandi from the Mahabharata – he balked at more conventional social attitudes. His mother partially accepted his coming out, but averred that she would still try to set him up with women, while conducting poojas and rituals that might “correct” his orientation.

Since then she might have come to terms with his choices (or not), but the mother and son seem to have reached an equanimous abiding with each other’s differences. Surely that’s a miracle? When love transcends expectations and understanding grows amidst complexities.

References

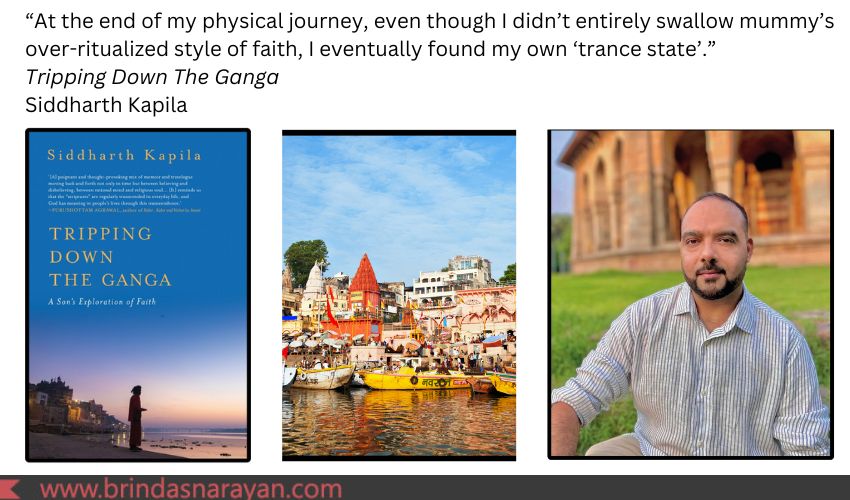

Siddarth Kapila, Tripping Down the Ganga: A Son’s Exploration of Faith, Speaking Tiger, 2024