Satirizing Publishing and American Race Relations

Yellowface might represent a striving author’s fantasy. Especially in the contemporary era, when there seem to be more writers than readers; when only a lucky few climb to bestselling lists or are feted at literary festivals, while others languish in the forgotten slumps of Amazon rankings. Of course, the ‘failing’ author might feel tangibly worse if the luckiest of the lucky few, someone who inhabits that rarefied intersection of the bestselling and feted, also happens to be a frenemy. A peer who attended the same college (Yale), who flaunts her ‘woman of color’ tag like a badge of honor, is noticeably better looking – “tall and razor thin, graceful in the way all former ballet dancers are” – and possesses oodles of an ingredient that evokes murderous jealousy: literary talent.

In her darkly comic novel, Rebecca Kuang explores how success can seduce the ethically undecided to cross the Rubicon. The book starts with the lumpy feelings of Juniper Hayward, the novel’s unreliable narrator. She’s white at a time when the publishing industry advocates or pretentiously flaunts diversity. Her debut novel has flopped, and she is forced to make ends meet with a career she might have derided during her Yale days: by rewriting SAT essays for a coaching institute. Of course, she hasn’t given up her literary strivings, but her ongoing attempts fail to possess the magnetic tugs that keep pages turning.

Hayward feels worse about her situation because her bete noire, the Chinese American Athena Liu scales global charts. Athena features on New York Times bestseller lists, wins awards, is translated into multiple languages and most aggravatingly, churns out prose with a slickness that eludes June.

Early on, when June and Athena have drinks together, the latter dies in a freak accident. Her death seems so effortless and childlike, it might stretch the reader’s credulity: Athena chokes on a pancake. It’s that blur between fiction and life, dreams and reality, truth and lies that Kuang intentionally treads on through the pages. Because as June is to discover, as the story progresses, death is easy. It’s living, as anyone who’s tried it can tell you, that’s difficult.

Athena’s death lures Hayward to commit an act that wouldn’t have been possible if the writer had used contemporary means to produce her work. She was famously secretive about her writing and had always used old-fangled means to generate her manuscripts – by handwriting outlines into moleskin notebooks, then clacking them out on typewriters. In an era, when cleverer plagiarists can hardly resort to CTRL-C, CTRL-V, covetous Hayward is granted a gift by the universe: the dead author’s draft of her latest work, all typed up, with no trace of it on the internet. She steals the pages, then convinces herself and the publishing world, that it’s really her work because she pours so much effort into rewriting it.

The stolen work delves into a historic time, set in a period when 140,000 Chinese laborers were deployed by the British on the Allied Front during World War I. June whitewashes it – makes the white characters more likable than they were in the original, prunes and edits and rewrites parts, to ensure that the boundaries between her and the stolen text are intentionally blotted out. She even willingly colors her own name, acceding to camouflaged suggestions from the publicity team. June Hayward morphs into Juniper Song, flaunting a middle name that her mother had accorded her at birth, and which now has a beneficial Chinese lilt to it. After all, in the woke era, the publishing industry is possibly tied up in knots, with a pervasive confusion about who is allowed to tell whose story.

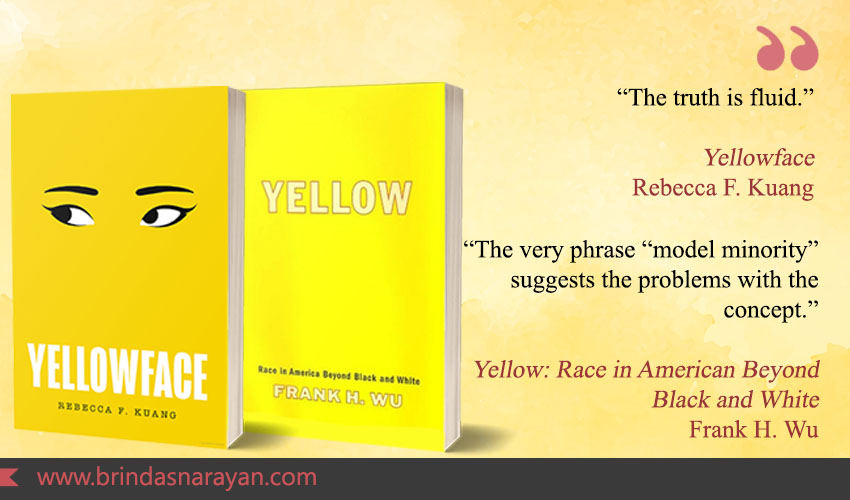

Eventually, Athena’s life, when unraveled after her death, does not seem as alluringly perfect as it once did. It’s a book that skewers the publishing industry as it does current equivocations about race. Reading Yellowface compelled me to return to Yellow, a compilation of essays by Frank H. Wu, who is currently the President of Queen’s College, City University of New York (CUNY). In this careful examination of what “yellow” means in the American context, Wu describes the experience of growing up as a solitary Chinese kid in a predominantly white suburb in the 1970s. His classmates not only hurled racial epithets at him but also tugged their own eyes into slits, with a question that reeked of disparagement rather than curiosity: “How can you see with eyes like that?”

That was only the beginning of a much longer journey that involved wrestling with various stereotypes that never quite disappeared as Wu traversed adulthood. Choosing to speak out for his race, Wu depicts how the “model minority” framing of Asian Americans can hurt rather than help. For one, it obscures variegation inside the community. Secondly, it is often used against African Americans, suggesting that they are not making it because of inherent or cultural issues, rather than historic or societal ones. Thirdly, it masks the racial discrimination that Asian Americans still face, turning them into a group to be feared rather than fostered. While Wu concedes that “the myth has a germ of truth”, the “truth” gets amplified and overhyped to the point of being distortive and hurtful. The very traits that are seen to lead to success are denigrated: “We are automatons, frightening in our correctness.”

And that perhaps is Kuang’s message too, albeit tucked into a white woman’s resentment and duplicity. Athena Liu was also boxed in, not allowed to write books that might have depicted non-Asian characters. Or even Asian characters that did not live up to stereotypical traits. She spent so much time living what seemed like a perfectly manicured life, she may not have had the chance to explore her messy self. That, ironically, is an exploration that June embarks on with not very pretty consequences.

References

Rebecca F. Kuang, Yellowface, The Borough Press, Harper Collins Publishers, 2023

Frank H. Wu, Yellow: Race in America Beyond Black and White, Basic Books (Perseus Book Group), 2003

Thanks for this review. This seems to a book that definitely should be read.