La Grande Jatte and The Anxieties of the Middle Class

Georges Seurat’s life was a brief flash on the planet. The French Neo-Impressionist painter, who lived in the 1880s, died of diphtheria at the age of 31. And yet, during his fleeting existence, Seurat accomplished a density of work that was to reshape the manner in which future artists would contend with perspective and color and technique.

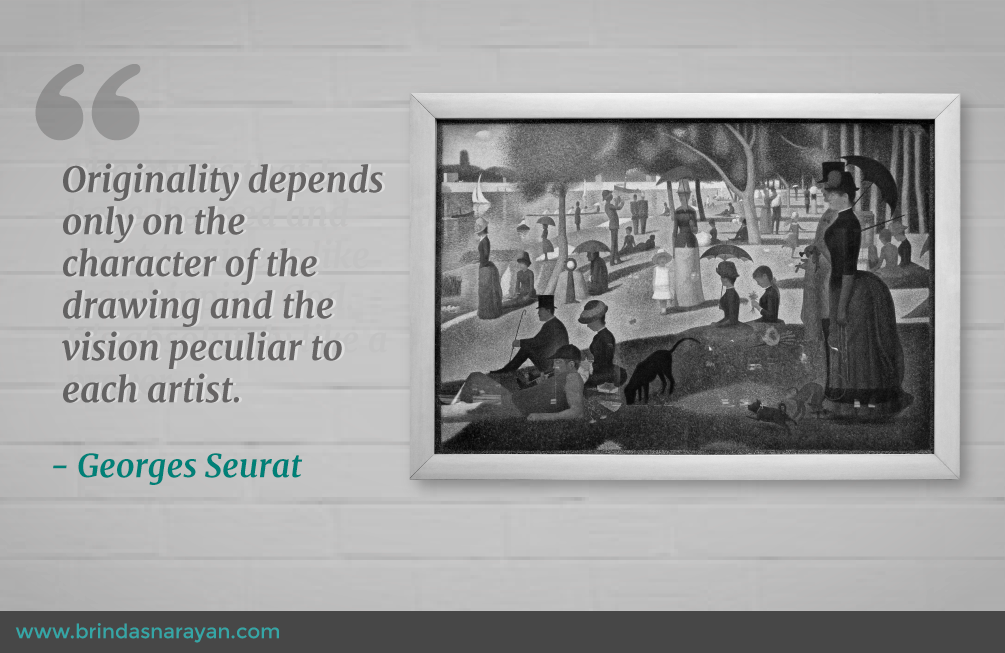

He was the inventor of Pointillism, a method by which tiny daubs of color are applied to a scene. Viewed from a distance, his granular strokes combined to create a luminosity that outshone other forms of painting. But his method was not arrived at impulsively. He spent intense years studying the theory of color and the manner in which the eye combines color to create a sense of the world.

Besides, he engaged in an astounding level of preparatory work before beginning his final masterpieces. For instance, his most famous painting, A Sunday Afternoon in the Island of La Grande Jatte, that currently hangs at the Art Institute in Chicago, was preceded by a series of oil studies and drawings. In each of those preparatory works, he experimented with diverse approaches. While his drawings toyed with stark blacks and whites, he fused colors and forms in his oil studies. His approach to art was akin to an architect who is compelled to create detailed blueprints before greenlighting any construction. In these preparatory works, which have been organized for public viewing at carefully curated exhibitions held at the MOMA (2007) and at the Art Institute (2004), viewers are shown the painstaking rigors the artist imposed on himself.

Even as Seurat recreated the future, he drew inspiration from the past, from both Classical and Romantic works, from realist and impressionist methods, from Michelangelo’s Florence and Titian’s Venice. In his penetrating review of the Art Institute’s exhibition, the ingenious art critic Jed Perl describes Seurat’s attention to details as well as his apprehension of larger themes: “He appreciated the sparkle of light on water as well as the formality of ancient art; he understood the importance of a full blast of color as well as the austerity of black and white.”

La Grande Jatte depicts working class Parisians who have recently acquired middle-class sensibilities. As the mute and somewhat isolated figures stare out at the river Seine, there is also a strange crackling in the atmosphere around them, a wit and mystery and surprise that surrounds their profiles. Each figure and the surrounding landscape was filled out by Seurat, one patient dot at a time. For the preparatory sketches and oil studies, he spent several days at the park, studying the movements and expressions and interactions between real people.

We must remember these were people who were ambivalent about their own status in society. After all, when people cross any cultural divide, East-West, North-South, or slide across an income divide, they are never sure of what markers they need to adopt. They are uncertain if they do belong to the new class or not. If they are real or pretenders. All those who have travelled and lived across national or ethnic borders, understand the anxieties such uncertainties can impose. But most people do not dwell on the hence perpetual anxiety of the middle-class. After all, when we dissect society into socioeconomic layers, the middle-class occupy the slice that invites the most trepidation. These are the people who can easily slip, with one wrong investment or one erroneous business decision, into the much-reviled (or even worse, much-pitied) lower-income groups. Even if such people do indeed scale ladders of success and reach, after years of self-sacrifice and diligence, the aspirational upper layers, they are often walled off from the cultural elite, from people who seem to carry with enviable facility, the language and codes and subtle gestures of frigid snobs. People who carry, in their exaggerated reserve or iciness, a mysterious appeal. The middle-class can scale the icy peaks of Mount Everest more easily than break into those chilling circles. As the author Manu Joseph notes in his piercing Mint article titled, Escaping India within India, “Affluent India is an archipelago of islands where people pay a premium not for quality but for the invisibility of other Indians. The Indian craving for social islands has only grown.”

Though there would be many middle-class or even elite people who are indifferent about belonging to the clubbiest of clubs, many others encounter the heightened walls only after they have toiled their way to the gates. Recognition by groups that matter to an individual, is unfortunately a deeper social and psychological need than most people would be willing to acknowledge. In his article titled “The Politics of Recognition,” the author Charles Taylor writes: “[Our] identity is partly shaped by recognition or its absence, often by the misrecognition of others, and so a person or group of people can suffer real damage, real distortion, if the people or society around them mirror back to them a confining or demeaning or contemptible picture of themselves. Nonrecognition or misrecognition can inflict harm, can be a form of oppression, imprisoning someone in a false, distorted, and reduced mode of being.”

Many parents would recognize that their child’s fitting into a social group is more important to their psychological well-being than any other social markers of success. The group can be small (as small as just one other person) or large, but it should be a group that matters to the child. A group that endorses that the child, with all its flaws and defects and vulnerabilities, is already perfect. Or at least worth befriending.

Perhaps, Seurat, who was, according a Wikipedia entry on the La Grande Jatte, “private to the point of secretiveness” harbored such insecurities. Someone who was ambivalent about his place in Parisian society. Perhaps, he related to the people, who stood on the Left Bank, some prostitutes procured by the bourgeoisie, some newly emerged from the lower classes because they mirrored his own ambivalence. Some of his people do odd things in the park. One woman holds a monkey on a leash, another dips a fishing rod into the river. At the center of the piece, a child dressed in white stares directly at the viewer, as if planted there to ask the poignant question: “What will become of these people and their class?” (Source: Wikipedia). A pointed question that, even in the modern context, in the face of growing inequalities, stays unanswered.