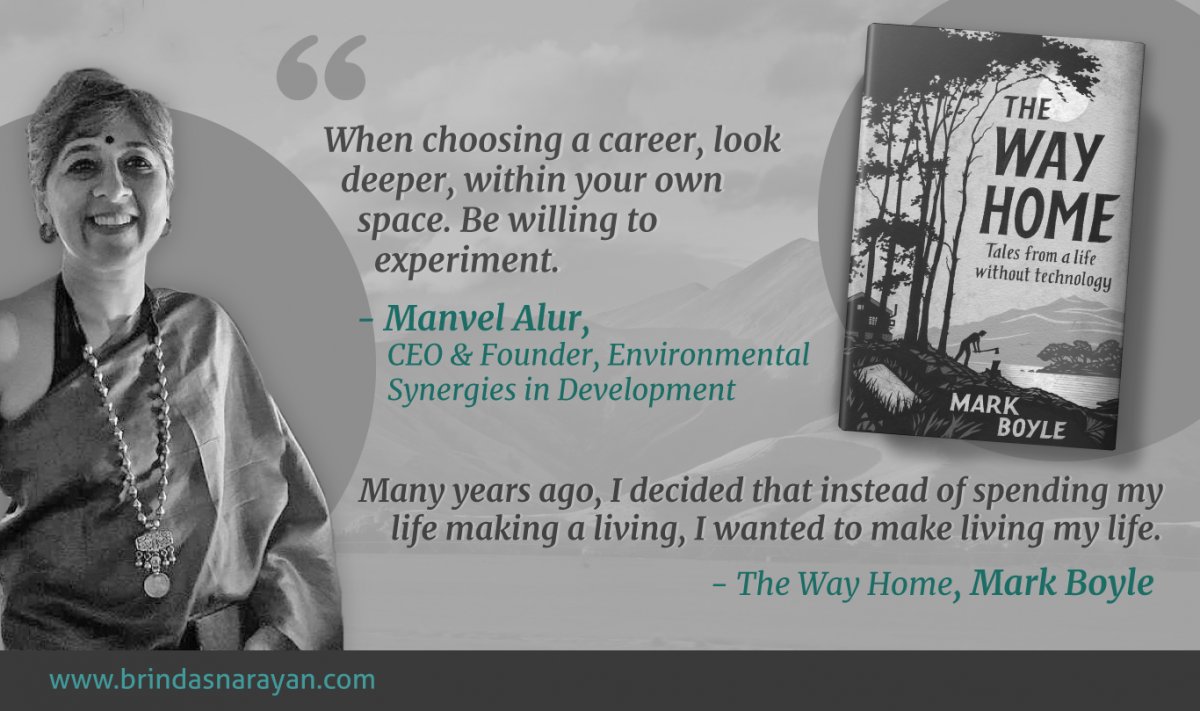

Integrating Work, Life and Place: Manvel Alur Champions Ecological Causes in the IT City

The Way Home: Mark Boyle Chooses to Live Without Technology

To relinquish technology in 1845, when Thoreau set out to live in Walden, doesn’t seem nearly as impossible as the feat accomplished by Mark Boyle, who adopted a similar retreat in 2016. At a time when those of us who are digital natives live in techno-saturated environs, Boyle, a Business graduate of Irish origins, resolved to live without electricity, “a phone, computer, light bulbs, washing machine, running water, television, power tools, gas cooker, radio.” A few years earlier, Mark had set up what seemed like another audacious goal: to live, in contemporary society, without money. He proved that it could be done, abjuring the use of money for a period of three years and capturing his experiences in a book, The Moneyless Man.

However, while deciding to spurn technology, Boyle was aware of how tricky it is to define “technology.” After all, even the pencil he used to inscribe his thoughts, the paper he carried with him, and “words” themselves can be considered the tools or technology of a previous era. Even as he was willing to acknowledge the hypocrisy and contradictions inevitable in such an exercise, he was intent on uncovering the “complexities of simplicity” rather than on being dogmatically “right”. The Way Home charts the story of someone who was, as Mark puts it, “attempting to pare the extravagance of modernity back to the raw ingredients of life.”

Conservationists or pioneers who had embarked on similar experiments in the past were usually attached to particular localities. For Thoreau, the transforming surroundings were Walden Pond, for the poet Wendell Berry, Henry County in Kentucky, and for the conservationist John Muir, the Sierras of the American West. Boyle established a relationship with a small patch of land in Knockmoyle, Ireland, an area proximal to woods and farms.

Manvel Alur: A Childhood Connected to Bengaluru and its Environment

Such emotive forging of place and person also seems to shape Manvel Alur’s life and career. Her strong impetus to contribute to the wider Bengaluru community might have been partially absorbed from her grandfather’s formidable legacy. Born in 1880 to a Madhwa family, Alur Venkata Rao, the Karnataka Kula Purohita or High Priest of Karnataka, steered the unification of Kannada-speaking people into a State that would bolster their linguistic heritage. Qualified as a lawyer, he was also a fiercely passionate journalist, the founder of a Kannada magazine, a historian, a freedom fighter and the author of more than 27 books. His renowned works include the Karnataka Gatha Vaibhava, a meticulous history of Kannadigas, and a translation of Bal Gangadhar Tilak’s Gita Rahasya from Marathi to Kannada.

Alur Venkata Rao’s artistic spark assumed a different character in Manvel’s father, who trained as an architect at the J.J. School of Architecture, and established his own architectural practice after working with Chandavarkar and Thacker for a few years. Besides imbibing the creative temper of her grandfather and father, Manvel gleaned an entrepreneurial daring from her mother. Flouting the norms of a generation that confined most women to homemaker roles, Neeta Alur built a small-scale enterprise that crafted handbags in the basement. A young, school-going Manvel watched a feisty all-women team do everything: forge ties with LIDKAR (the leather association), source raw materials, design bags, discover markets.

However, when it came to the careers of their three kids, her parents, while being “very particular that each of [them] should stand on [their] own feet,” desisted from slotting them into narrow mainstream options. “My Dad always knew that each of us had different skill sets,” she says, recalling their progressive mindset with gratitude.

Growing up as an energetic outdoorsy kid who reveled in sports – basketball, TT, swimming, badminton – as well as in running long distances and cycling all over town, Manvel found herself drawn to the gripping writeups and pictures in National Geographic magazines. She was among the few who read each issue “end to end,” captivated by the intricate makeup of the natural environment. Wishing to associate more closely with bewitching flora and fauna, she even reached out to the magazine’s editorial team, pitching herself as a young enthusiast from India, who would be thrilled to contribute “pictures or articles.” The team was gracious enough to respond. While appreciating her verve, they encouraged her to connect again, after accumulating “years of experience.”

The Way Home: Boyle Pivots to an Offbeat Life

As an average student at Primary School, and despite winning a scholarship to secondary school, Boyle wasn’t compelled by any particular subject. Since he performed best in Business and Economics, he decided to pursue those subjects at college.

His pivotal moment occurred outside college. At Edinburgh, when working at a supermarket, he shopped at a “cheaper” supermarket for his own groceries. Till then, he assumed that “cheaper” meant “better” without dwelling on how low prices might trickle down to farmers and to other ecological systems like rivers, fish, forests. One day, at a grocery aisle, when picking up a package of organic tofu, he happened to read the marketing story behind the product. He felt that he wanted his own life to weave more purposefully into the natural world, and he quit his supermarket job and joined an organic food store as a Store Manager.

During this period, he also encountered the works of Noam Chomsky, Naomi Klein, Vandana Shiva and Jared Diamond. But, at some point, working more than 60 hours a week for a company that contested sweatshop conditions in Southeast Asia seemed self-defeating.

Taking a break, he rented out a houseboat, and reflected on what the trajectory of his life should be. One evening, in 2006, he decided that he wanted to try living without money. He wished to distance himself from an economy that led to ecological erosions and other unjust practices that he did not support. Displaying a remarkable turnabout for a Business graduate, he said: “Money enabled me to float around cities, enjoying the fruits of everything I didn’t like about the industrial world, without ever having to meet real life – blood, death, shit, dirt – on its own terms.”

Of course, he did not know exactly how he would go about doing this. After all, in the contemporary consumerist context, it almost feels easier to live without oxygen than to live without money. At first, he created a website, where anyone could offer “skills and tools” for free within local neighborhoods. He intentionally skirted all the other e-commerce trappings like reviews, adverts, ratings and so on. He was surprised by the rising popularity of his enterprise, a skeletal operation that he ran from his bedroom. Members from more than 180 countries starting using his platform to lend or offer their skills inside communities.

In 2008, when he formally announced that he was going to live without money, he was flooded by media calls. He felt discomfited by all the attention, since he wasn’t sure if he would last out for a whole year. As it happened, he did manage to carve out a moneyless existence for three years – an experiment captured in his book, The Moneyless Man.

After re-emerging into the moneyed world, he encountered Aldo Leopold’s essay, Thinking Like a Mountain. This engendered a shift inside him about life and death. He keenly felt the interdependence of everything inside the planet, and wanted his life to reflect his internal transformation. He was also keen on erasing the pretensions of civilization and culture from his day-to-day existence. While marveling at the aesthetics of a bird’s nest, he could not help be moved as well, by the lack of ownership and conceit in the winged artists. Sensing that humans have lost such a “natural” connection to the world, he intended to regain it, at least for himself, and a few others who might be interested in exploring such a minimalist existence.

This led to his construction of a cabin in Knockmoyle, along with a separate space for his guests/visitors to reside (on non-commercial terms) while they hung about watching him or experiencing their own affinity for nature.

Manvel Alur: Builds Her Environmental Expertise

On completing her PUC in Mount Carmel’s in the mid ‘80s, Manvel was at a crossroads. She had to pick between two choices: an Electronics degree which heralded a pragmatic and financially-stable career, and the very recently established Bachelor’s in Environmental Studies at St. Joseph’s Arts and Science, a program with relatively unknown prospects at that point. Like most Indian youngsters of that generation, who were insecure about their financial futures, she picked the familiar and practical. But even as she stood in the queue with her parents to pay the fees for the Electronics degree, her heart was tugged in another direction. “I started crying, saying I don’t want to do Electronics.” Fortunately, her father encouraged her to pursue the relatively unexplored option. She signed up for Environmental Studies and completely immersed herself in material that had always compelled her through childhood.

She recalls her extremely well-structured three-year course at St. Joseph’s as a judicious mix of Theory and Practicals. For instance, when her class conducted Air Quality Analyses and Water Quality Analyses between the mid-‘80s and the early-‘90s, when the city hadn’t yet mushroomed into its current sprawl, she was dismayed at how alarming the readings already were. Their program also incorporated several forays into forests and other natural terrains, like Bandipur, Periyar, Mudumalai, Thekkady and Mekedatu. In one of her inspiring lessons, a Professor pointed to a lone dead log inside a forest and then identified all the living linkages between that log and the heaving greens and other life forms around them. Trampling around in wooded areas came with their own perils. Once, while trying to capture an elephant herd on her Dad’s camera, she was chased by one of the infuriated clan members.

Alur also displayed another trait at college, an attribute that would prove critical as a future champion of ecological rights. When a fellow-student at class asked “what seemed like a sensible question, the Professor brushed her aside, and this irked me.” Manvel politely and firmly backed her classmate’s question, pointing out that it was a valid one and deserved a response. The Professor dismissed the viewpoint coming from an audience that did not possess a degree yet. Manvel and a few others stood their ground, and even walked out of the class to reinforce their support of legitimate voices and free speech inside the classroom. They were temporarily suspended from college for asserting their dissenting views, but Alur realized she was willing to be termed a nonconformist by folks with “Authority” in order to uphold higher principles.

Meanwhile, the city around her was morphing at a frenetic pace. Some concerned voices were starting to express concerns about the side effects of “Growth” and “Progress”. The then Director of Max Mueller Bhavan wished to cohere with other like-minded people. While still at college, Manvel connected with him and helped garner a group of thinkers, activists and involved citizens, including the Chief Secretary at that point, Dr. Ravindra, Anselm Rosario (currently the Managing Director of Waste Wise), Leo Saldhana, a fellow student who evolved into an environmental activist and others. This informal group catalyzed the formation of the non-profit organization, CIVIC, which continues to raise critical citizen issues on several dimensions.

Wishing to study further, Alur chose to pursue a Master’s in Environmental Studies at Aberdeen in the U.K. Returning to India soon after, she joined Equitable Tourism Options (currently called Equations). As part of a team that analyzed the impact of fishing along the Western Coasts of Karnataka, she often stayed in small shacks and other ramshackle joints. She also studied the effects of tourism in Thailand, especially the impact on sex workers and the ramifications for drug control.

Once, while hiking in the northern parts of Thailand, she contracted malaria, and was left in the care of a village family while her group trudged onward. Accustomed to rough trekking experiences, she remembers bumping her way down river streams, “entirely on our butts.”

The Way Home: Boyle Liberates Himself from Mainstream Tugs

Such physical hardships and intimacy with the landscape also marks Boyle’s life in the woods. His everyday routine at the cabin involves heavy manual lifting, shoveling, fixing, digging and so on. Once he carted stones to lay a path through an area, loading and pushing the filled wheelbarrow, and fitting the heavy stones into place. Since the work required the use of almost all his body parts, he could feel at the end of such jobs, the intense aliveness of each muscle and organ, sensations rarely encountered by those of us with sedentary jobs.

At another time, he embarked on a wine-making project, that entailed plucking gorse flowers from spiny bushes. The task required extraordinary levels of mindfulness, since inattention would result in a hurtful prick. Occasionally, his mind dwelt on the sensual nature of such transitory moments: “My face is soaking up the sunshine, my nose full of coconut, my fingers tingling from the spines, my eyes marveling at the peculiar and extravagant insects flying around me, each of them absorbed in their own work.”

Though he had been a writer, Boyle intentionally switched off from the news since 2015, a year before the start of his cabin experiment. Reading Robert Colville’s The Great Accelerator, he was aware of the manner in which time has speeded up in modernity, so that we currently live in an environment where every “nanosecond” is treated as a monetary unit. At the cabin, heeding only natural light and the turn of seasons, he feels privileged in not having to heed a clock or an alarm. He lives, by Irish standards, at a fraction of the poverty line income, but he feels “money poor” and “time rich.” Though physically exhausted by his chores, he is liberated from the constant gnaw of material desires and accompanying financial strains.

Manvel Alur: Creates Her Own Environmental Enterprise

Like Boyle, Alur too eschewed the lures of a mainstream job and continued to train her attention on the ecological spillovers of development projects. During a seven-year stint at TERI, she learned to integrate social dimensions into Environmental Impact Assessments (EIA). Travelling to coal mines like Dhanbad, Neyveli and Bhokaro, she determined the forms of rehabilitation offered to displaced people, the issues of job security and health for coal workers and the other social runoffs of such large-scale projects. Staying at a barsaati in Delhi during this period, she relished her autonomy and self-sufficiency – toughening herself on daily commutes in a city that’s still considered unsafe for women, cooking for herself and managing other household chores.

Marriage ushered a move to the U.S., where she joined the Energy cell at The League of Women Voters, studying how Government Policy on Nuclear Energy impacts local communities. At the Princeton Energy Resources Institute, where she worked at next, she focused on environmental database assessments. Later, at Chemonics International, she was involved in Energy and Environment projects in places like Kyrgyzstan, Philippines and India.

In 2002, by which time she also had two daughters, she moved with her family back to Bengaluru and spent 13 years on work-from-home arrangements, in various consulting positions. She supported International Funds, including the World Bank, on Climate Change Mitigation, and also consulted extensively on Carbon Trading, before the carbon market unfortunately collapsed in 2015.

Soon after the kids were grown up, she wanted to leverage her rich experience across various environmental contexts to deepen her impact on the city.

In 2016, she founded Environmental Synergies in Development (ENSYDE), a non-profit organization and is currently one of the prominent environmental leaders in Bengaluru. Ensyde works with citizens and organizations to drive processes and behavioral changes that shrink the carbon impact and other hazardous runoffs in Energy, Water and Waste systems. They also galvanize next-generation leaders with sparky education programs. One of their well-known initiatives involves a partnership with Saahas to foster awareness and implement responsible collection and recycling of e-waste across the city.

Both Alur and Boyle live by the credo voiced by the poet Wendell Berry in The Art of the Commonplace: “My wish simply is to live my life as fully as I can. In both our work and our leisure, I think, we should be so employed. And in our time, this means we must save ourselves from the products we are asked to buy in order, ultimately, to replace ourselves.”

References

Boyle, Mark, The Way Home: Tales from a Life Without Technology, Oneworld Publications, London, 2019