Shelled Secrets: Unraveling Mysteries in Modern India

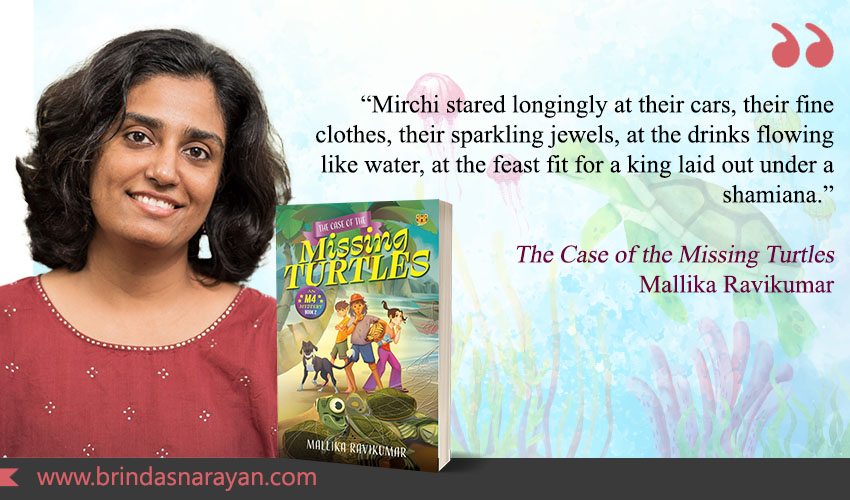

Sometimes all it takes to retreat into a forgotten childhood is to pick up a children’s book. The Case of the Missing Turtles brings back the thrilling vibes once evoked by the Five Find-Outers (one of Enid Blyton’s mystery series that had many of us conjuring mysteries in our own humdrum backyards).

More delightfully, the M4 operates in contemporary India, unraveling puzzles layered with the frisson of class and caste, of jungle and city. The young detectives’ club is injected with the mosaic makeup of the nation, with shards of bastis and bungalows. The four Ms in M4 are Mirchi (a local scrap-collecting boy who lives in the Anand Nagar basti), Meera (the Senior Superintendent of Police’s daughter), Malhar (the SSP’s son) and Munna (Mirchi’s dog).

Already famed in their neighborhood for their racket-busting smarts, a teary-eyed fisherman’s son, Shimplya, bounds to Mirchi when his father is inexplicably arrested. Apparently, the hapless fisherman was snapped up with a basket of turtles and cash. Sea turtles are safeguarded under the Indian Wildlife Act of 1972.

When Mirchi ropes in his partners, Shimplya emphasizes that his father would never harm turtles. Pointing to a turtle tattoo on his arm, the boy avers that they belong to a turtle-worshipping tribe. Paradoxically, his father had been trying to dissuade other fishermen from using trawler nets, to prevent turtles from being tangled up with fish.

Outside the police station, Meera bumps into her photography teacher, Isaac, and his wildlife biologist girlfriend, Akhila. The biologist is at the station about a case related to turtles, so Meera’s ears perk up. Does this have to do with Shimplya’s father? When Akhila notes that the haul on the fisherman’s boat consisted of inland or freshwater turtles rather than sea turtles, their suspicions are confirmed. The turtles were planted there by devious enemies.

Though this book is targeted at middle-grade and teenage readers, Ravikumar carefully weaves in the “greys” that come with criminalizing certain behaviors while condoning others. Starting with the colonial era designation of entire communities as “criminal tribes” with the Criminal Tribes Act (CTA) of 1871. Formulated by the British as a response to the 1857 rebellion, the CTA, in one wordy swoop, outlawed the activities of some pastoralist, craft and forest-dwelling communities among others.

In one of the more touching scenes in this book, the tribal kids try to articulate this to the young investigators. Named, ironically enough, after modern objects like “Bisleri” “Bypass” “Bottle” – these kids become pawns in bigger games of wildlife poaching, drugs and guns. But their own lifestyles have been banned or criminalized, without the anchoring succor of viable alternatives. As one of the tribal girls puts it, “You promise us land and jobs but deliver nothing! Do you have any idea how we pulled through your lockdowns during Covid? It is the jungle that fed us. The jungle that sustained us. Who will care for the jungle more than us? And you big officers come around in your big cars, making us into some wicked poachers out to destroy the jungle.”

With villainous, thuggish businessmen who harbor political ambitions, corrupt and brutal police inspectors, Missing Turtles might feel like a bleak take on contemporary India. On the other hand, it’s also peopled – like our country – with as many redeeming characters. Like the SSP, Meera and Malhar’s father, who’s imbued with an admirable incorruptibility, and an intent to bring only the “bad” folks to brook.

Or equally hearteningly, Vanaja Narula, a Deputy Conservator of Forests (DCF) committed to the cause of forest conservation. While also being attuned to inbred biases in her own staff and to historical injustices meted out to tribals. The DCF tells Meera that women can do anything. Including becoming forest officers: “I have done it all – walking in waist-deep water full of leeches, trekking in high altitudes with low oxygen, chasing poachers, dangerous smugglers, fighting the timber mafia, illegal miners. I have seen a lot in my twelve years of Forest Service.” Despite this, the staff still call her “Sir” because they’re so inured to having male bosses.

Or Madhavi Pradhan, a kick-ass lawyer, and the detectives’ mother, who’s unafraid to represent the poor fisherman. The corrupt inspector is shocked that the SSP’s wife would represent someone so bereft of power. At the end, loose ends are tied up, crooks are nabbed and justice is served.

Mallika Ravikumar is a lawyer-turned-writer, who also conducts tree walks and runs a YouTube channel titled “Tree Talk with Mallika Ravikumar.” Her legal expertise shines through in revealing that there’s nothing natural or inevitable about our laws. And that even conservation movements cannot be fanatically focused on listed species, without considering human lives and ancient practices that have been braided into such environments. Moreover, as Ravikumar depicts here, it takes clear-eyed children to call out the hypocrisies and affectations in adult lives.

References

Mallika Ravikumar, The Case of the Missing Turtles, Talking Cub (Speaking Tiger), 2024