Moxie on Wheels: Voyaging with Sandra Gail Lambert

Overcoming Obstacles, Charting Paths

Sandra Gail Lambert was only 10 years old when she realized that she would have to forge her own pathway through an unfriendly world. The obstacle she confronted then was a physical one, waist-high bus steps that she would have to navigate with crutches and a clumsy leg brace.

This was America in the 1950s, and Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act (1973), was quite a while away from being signed into law. Watching Sandra struggle up those steps, her school Principal decreed that she should be sent to a different school. To one dedicated to the “handicapped”. Merely because she couldn’t navigate those steps without adult help.

The hefty bus driver with a “cigarette-gruff” voice decided otherwise. She took it upon herself to train Sandra on her own. Not only to navigate those steps with her crutches and brace and school backpack, but without revealing her panties (pants weren’t an option then for little girls). Lambert conquered the steps.

She stayed on at that school. And later, charted her course through an equally inhospitable college where she had to wrangle with an administrator to use the handicapped parking slot. Or scurry between classes at opposite ends of the campus within 10 minutes – and despite making her way as fast as she could, she was always late. Always missing crucial announcements and beginnings.

Sandra was, what is called, an “old polio.” Folks who were struck by polio, before the disease was eliminated by vaccines introduced in the 1950s and 60s. Without the kind of “rights” that flowed through to other disabled groups later, they were a cohort that had to work extremely hard without complaint.

They couldn’t, for instance, like other women, seek time off for “self-care” – a notion that swept into modern parlance since the 1980s. As Lambert puts it, unlike assertive feminists who could afford to draw personal boundaries between life and work, care for the self and care for others, she had to work 13-hour shifts just to keep her job. If she asked for time off, the assumption would be that she was seeking this because of her disability. Which would then lead to another false conclusion: that disabled people couldn’t be counted on to complete full shifts.

Forged by her tough childhood and the historical period she lived through, she grew up a fighter. Not just for access, or rights, but to carry her body into spaces, and be present. “My resilience, the dignity I find in endurance, my adamant belief that help is fine but to always make sure you can do it on your own…”

Currently in her early 70s, her identity is still tied up with being disciplined, with working her way through physical spaces. She can’t think who she would have been if life hadn’t been this hard. If her life hadn’t been this way, she would have faced a kind of loss: “I’d have to be a different person for this not to seem like a loss.”

With the hindsight of accumulated experience, she can also take a step back to watch and imagine anything she wants to. Younger folks with conditions similar (but also different) to hers do stuff that she could have never dreamt of in her youth. There are women who somersault on wheelchairs, others who pole dance. Perhaps, she too could pole dance. And she no longer cares about outdated strictures of the 1950s. So if she does pole dance, she wouldn’t care about baring her panties, or thighs or breasts decorated with “glitter and rhinestones.”

Finding the Key to Love

Growing up queer and disabled, she didn’t grow up with the fantasies of other kids. She didn’t expect to have marriage, parenthood. So when it came to relationships, she studied people. And scoured websites for tips. In the meanwhile, her friends kept trying to set her up. Usually, her coupled friends.

But in all their brief encounters over the years, Pam always ignored Sandra. Another friend suggested she ask three women out. She said dating inevitably involved humiliation. All three turned her down with awkward “twirly-eyed” nos. She finally summoned the gumption to ask Pam out on a dinner date. All through, Sandra was a robot and was sure the evening was a massive fail. Pam called her back anyway. She said there was one shining moment when the real Sandra shone through and that was all she needed.

Then they had a fight. They were waiting by the side of a street, when a lady driver screeched to a halt. Sandra refused to budge. Pam said the woman was just being considerate. Sandra felt infantilized, diminished. Treated like a toddler who might run across a street unbidden. The woman waited and waited and then drove past. Pam thought Sandra was being too sensitive, feeling slighted by every small incident. Sandra felt she had a right to feel that way: “…I’m the one with experience. I know what I’m talking about.”

When Pam finally moved in with her, Sandra insisted that she would take charge of one detail: the placement of Pam’s piano inside her apartment. Because she knew that wherever “the piano goes, Pam will follow.”

Writing Beyond Labels

When turning to writing, in her 40s, Sandra sought feedback from other writers. She had written a short story about a character who was disabled and a lesbian. When she sent it to a college professor for feedback, she was asked to shave off the lesbian bit. She was told the character was too “messy” and besides, it wasn’t adding any tension to the plot. She decided to do the opposite: to heighten the queerness of her character, with the kind of drama that would draw readers in. But in the process, she lost some of the deeper themes she had been exploring. “Each time I read the story, amid the applause, I mourned.”

Later she discovered the larger writing world dotted with conferences and snobby editors. She started sending her work to journals, till she was receiving handwritten rejection notes – a sure sign of one’s climb up the ladder. One editor said he wanted to know, “for some reason” about what it really felt like when she was swimming. Like as he put it, “about useless legs trailing behind her as she swam?” While she decided to discard this feedback – why would she feed into already-prevalent biases of disabled people – she found other useful nuggets.

Since she uses a wheelchair, writers at workshops have told her that she ought to announce that in the first paragraph, or first sentence. As if it always ought to be the overwhelming attribute about her. Whether she was writing about “lesbian love, wilderness exploration, mother/daughter relationships”, they wanted to hear about her legs. “Why would I think about my legs all the time?” They tell her to write more honestly, to dig deeper, but they give her descriptors that they think she should use for her legs. Words like “useless” or “withered” and that’s not how she thinks of her legs.

Besides, “honestly” she doesn’t think of her legs all the time, or even every day. Can they get that? In the process, she always gleans “sideways” insights. Sometimes, “[even] the straight-up, blithely unaware ableist comments are valuable.”

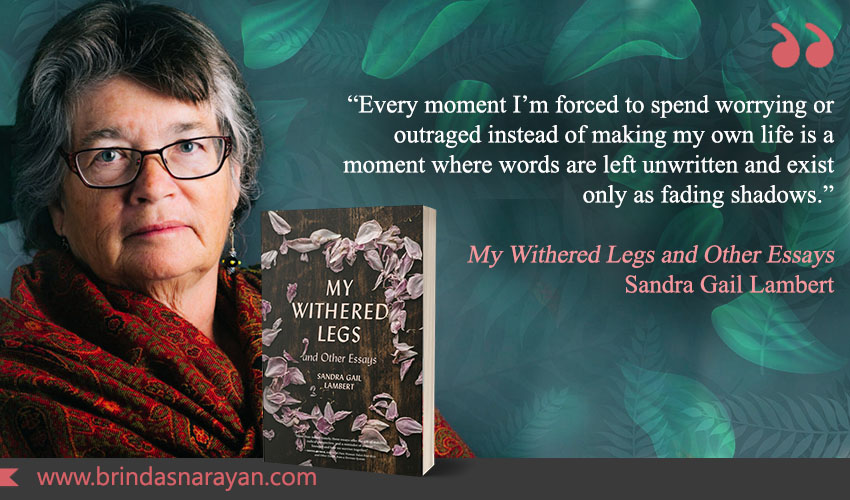

This collection of essays by a deft writer evoke the challenges and comical moments of turning to writing later in life, while also dwelling on many other things: mother-daughter relationships, awkward dinner dates, queer identity, climate activism, rejection letters, patronizing ableists, a cancer diagnosis and so much more. Spend time with Lambert, whose wit and buoyant charm might just shift your perspective.

References

Sandra Gail Lambert, My Withered Legs and Other Essays, University of Georgia Press, 2023