Peak Revelations: Navigating Life in Never Never Land

A question is often posed of a new friend or potential life partner: are you a beach or mountain person? The answer perhaps is immaterial, but the question might be trying to uncover something else: how do you handle change? With the towering stoicism of a mountain, or with the lapping acceptance of an ocean?

In Never Never Land, its middle-aged writer protagonist, Iti Arya, retreats to the mountains. Especially when she feels adrift in the city, while trying to complete a novel. The stilted cheer of a school WhatsApp group heightens her alienation. She leaves for Kumaon in the Himalayas, to the Dacha, a cottage inhabited by her grandmother, Badi Amma. She hasn’t seen her in a decade, though she used to visit her often earlier. Badi Amma, now in her 90s, lives with Rosinka Paul Singh, a centenarian. Though Badi Amma used to work as Rosinka’s househelp, both women seem to welcome Iti with grandparental fondness.

This time the Dacha also enfolds a mystery, a blonde-haired, blue-eyed young adult called Nina whose unexpected presence aggravates Iti. After all, she might have been expecting to have the grandmas to herself. Moreover, the roots of Nina’s hair are black, as are her eyeballs behind blue contact lenses. To meet a stranger is one thing. To meet one who projects fakeness with a youthful insouciance is doubly vexatious, especially when one is trying to escape the ebbs and flows of virtual worlds, to live among the substantive roughs of a mountain. To make the situation more confounding, the young woman claims that she’s also Badi Amma’s granddaughter, which would make her Iti’s cousin.

Iti herself has had a troublesome past. Her Mom had intentionally distanced herself from Badi Amma after her marriage to a chemist. “She had been deeply mortified by her mother’s existence as a menial, a mere maid.” And she had barely played a part in Iti’s life. Iti had grown up in a boarding school, visiting Badi Amma during her holidays. And was inevitably woven into the life and memories of Rosinka. So when Rosinka asks her why she’s back now, inside the stultifying placidity of Kumaon, she says: “Too much screen time.”

While exploring the deep fissures and magnetic pulls between intergenerational characters, Gokhale also examines an overriding Indian theme: class. Between the mistress (Rosinka) and her maid (Badi Amma), occasionally there’s camaraderie. Then again, authority is reasserted, when commands are issued. Which melts once more into a seemingly warm relationship. When, however, they start digging into the past, with sepia-toned photographs, unsavory secrets spill out.

Rosinka’s husband, a photographer, had taken a picture of the young “Lily” – Badi Amma’s name inside the household. A jealous Rosinka had once slapped her so fiercely, marking her face with red welts. After that incident, Lily extracted her revenge. She became Peter’s lover. If Rosinka could cross lines, so could she. Then Peter died. But Rosinka wasn’t done. And Rosinka burned her with hot nettles soup. As if she had always been harboring an internal rage that had merely been seeking an object. All that anger has perhaps been boxed up, not forgotten or forgiven, but taped over for convenience. It’s the two women, withered by life, who offer solace to Iti now. Merely, perhaps, by their tenacity to keep going, even as candles overcrowd birthday cakes.

With time, other truths surface. Nina, apparently, is not Badi Amma’s granddaughter, but Rosinka’s grandniece. She was gifted to an orphanage, but returned to claim her share of property. Origins apart, Nina also displays the tempestuous flipflops of the young. She steals two Nicholas Roerich paintings from the household, and elopes with a café owner. Whom she then squabbles with, runs away during a deluge, and holes herself up in a cave. Which then gets blocked up during the storm, requiring emergency operations to swing into a public, media-watched rescue. A somewhat bashful Nina returns with her leg in a cast, bringing back the slashed paintings and restoring a new kind of order to the Dacha.

But that perhaps is Gokhale’s theme after all: the messiness of life, the seeming disorderliness. And yet, as Iti observes, occasionally the shards of beauty, or glimpses of a higher design shine through. “Perhaps it was like a spider’s web with its concentric circles and intuitive geometry. There was a pattern to life, in recurrence and circularity, in seashells, in poetry, in the Fibonacci sequence. And yet it was arbitrary and unpredictable.” Gokhale, who has also penned nonfiction works in mountains, including one co-written with Ruskin Bond, gets how these landforms can evoke both rapture and dread.

In this digital age, when most of us deal with persistent distractions, Never Never Land is like a much-needed meditative interlude. It’s telling at the end, that Iti abandons her school WhatsApp group, content as a solitary outsider. To pay attention to the small and priceless, sometimes we need to climb Himalayan heights.

References

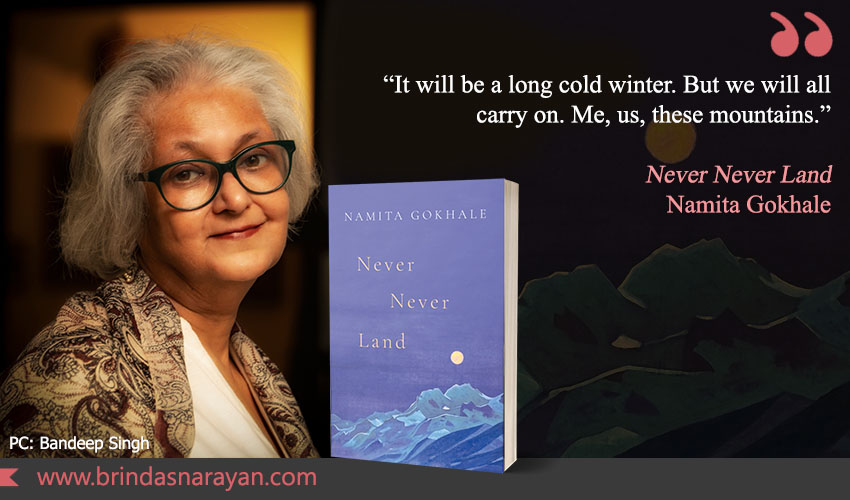

Namita Gokhale, Never Never Land, Speaking Tiger Books, 2024